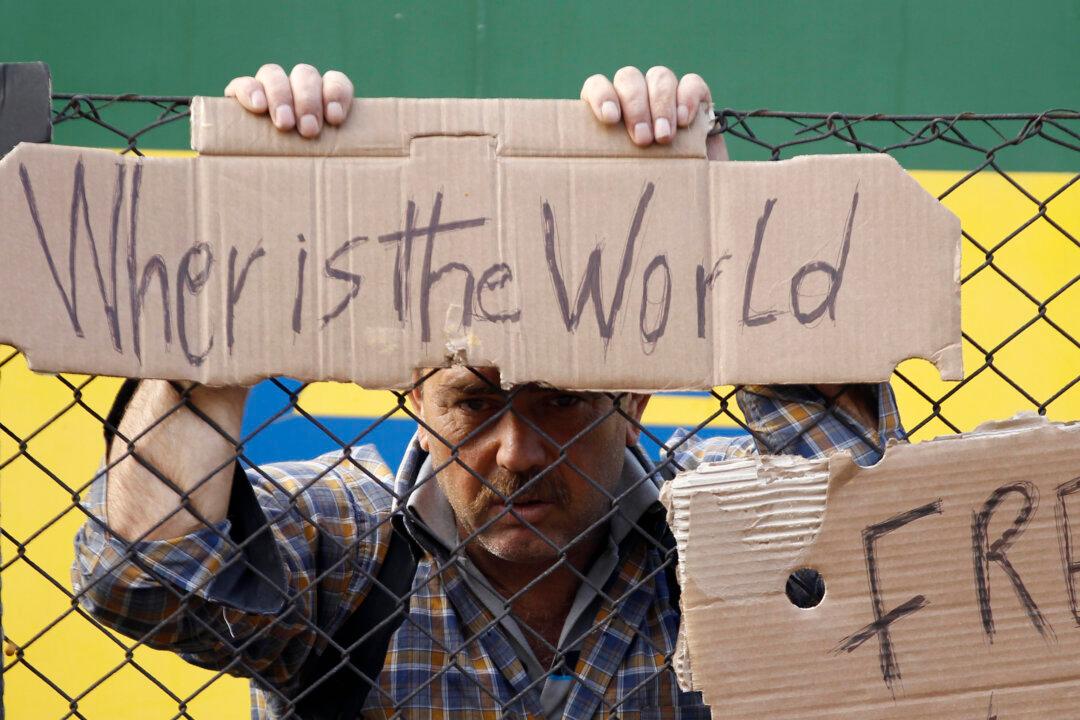

Not since World War II has Europe faced a refugee crisis comparable with the situation unfolding at its borders at the moment. The European response has been, to put it mildly, ambivalent. On one hand there has been a mass outpouring of sympathy in the media and in public debate for the refugees fleeing nightmarish situations in Syria and Iraq. On the other, elected governments have not come up with solutions that seem remotely equal to the task. The circumstances are extreme but the pattern is nothing new. The EU has struggled to get member states on board for a system of burden sharing.

Germany is taking in up to 800,000 refugees but even faced with mounting pressure at home, British Prime Minister David Cameron could only bring himself to make a vague promise about doing more. In a speech on September 4, he pledged to help “resettle” thousands more refugees, but made no firm commitment to easing access at the UK border. Meanwhile, countries in Eastern Europe continue to close their borders and seek to unburden themselves of the people arriving in their towns.

Most people would like to see innocent refugees and their families find sanctuary, safe from the threats of death and persecution. This stems from humanitarian motives and not from narrow self-interest. We can therefore think of refugees who gain protection as what economists call a public good.

Public goods are things that have a non-rivalrous and non-excludable benefit. Non-rivalrous means that the good feeling I get from knowing that refugees have a safe haven does not diminish the warm glow that you get from it. Non-excludable means that, supposing refugees were given protection, then neither you nor I could be excluded from the satisfaction that it would bring.

There are costs for the country accepting refugees though. They are financial and probably social too. So there is an incentive to sit back, let other countries do the heavy lifting, and reap the benefit of their efforts. But if every country does that then very little heavy lifting gets done. In the absence of some higher authority to determine each country’s contribution, the public good will be under-provided and we may all be worse off. It is a classic collective action problem.

The Common System

For two decades the EU has been developing a common asylum system. This has focused on harmonising various components of asylum policy, but not on burden-sharing between member states. The preference has been for countries to voluntarily offer places for refugees at times of crisis rather than to enforce a more binding allocation system. That is, until now. In May the European Commission called on every member state to take in a certain number of refugees, according to their individual capacity. Richer, larger countries would be asked to take more, smaller, less wealthy member states would be asked to take fewer.

The scheme is not binding though, and it has been impossible to get all countries to commit even to the modest numbers proposed. Instead Germany has led the way while many of its European partners sit on the sidelines – an example of what Mancur Olson, doyen of collective action, dubbed “the exploitation of the great by the small”.