Xi Jinping, the presumed next head of the CCP, tried to withdraw from assuming leadership of the Party, but was convinced to stay on by Party elders, who feared the warring factions could not agree on anyone else but him. This article explores why he did this. This is Part 2 of the series; you can read Part 1 HERE.

On Aug. 15 a group of 14 people took boats from Hong Kong to the Diaoyu Islands—called the Senkaku Islands in Japan. Seven of the group stepped on the island carrying Chinese flags and declared the islands belonged to the People’s Republic of China. They were almost immediately detained by the Japanese.

The landing on the islands applied a spark to the dry tinder of Chinese nationalism and hatred for Japan, and China erupted. Mass anti-Japan demonstrations broke out in major cities throughout China. Among the slogans the demonstrators carried: “The Diaoyu Islands belong to China, Bo Xilai belongs to the people.”

The world’s media reported on these demonstrations as the latest expression of Chinese nationalism and understood them in the context of China’s attempts to assert claims to the South China Sea. Sources knowledgeable about deliberations in the highest levels of the CCP consulted by The Epoch Times for this report tell a different story.

Hu Jintao, the head of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), saw the landing on the islands as a declaration of war by Zhou Yongkang and the Jiang Zemin faction against Hu Jintao, Premier Wen Jiabao, the presumptive next head of the CCP Xi Jinping, and those loyal to them.

A meeting in May at the Jingxi Hotel in Beijing had been meant to bring peace to the two warring camps. Hu Jintao had brought together 200 of the top figures in the CCP and cut a deal.

Zhou Yongkang and others would be allowed to separate themselves from Bo Xilai, not being implicated in his being brought down. Zhou Yongkang would be allowed to have a public presence until the 18th Party Congress, but would retire completely after the Party Congress. Zhou also gave up the right to appoint his successor as head of the Political and Legal Affairs Committee (PLAC), an all-powerful organ of the CCP that controls nearly all aspects of law enforcement.

Hardliners in the Party agreed to support limited political reforms, which would include “high level, free elections,” with Guangdong Province used as a testing ground for the reforms.

Veteran Party leaders had helped promote the Jingxi meeting, but the two sides had come to it with different agendas.

In the months following Wang Lijun’s attempted defection on Feb. 6, Zhou Yongkang had been pressed hard by Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao. He had been put under internal control and no longer called the shots in the PLAC. Those closest to him in this powerful organization had been removed, and institutional changes to it had been agreed upon that would reduce its power in the future.

Zhou had reason to fear that if he didn’t agree to a deal, he would be prosecuted like Bo Xilai.

Hu Jintao had realized that Bo Xilai’s crimes involved too many Party officials. If all of the guilty were prosecuted, the Party would be pulled apart. Hu agreed to the Jingxi deal to save the Party.

At the same time, the economic news in China was terrible. The Chief of Staff of the State Council had said at a meeting that economic dynamos of Shanghai and Zhejiang Province had not registered 7 percent growth over the past year as had been reported—their economies had actually contracted.

Many companies in the once prosperous city of Dongguan had gone bankrupt. Local governments were having trouble meeting payroll. Economists predicted a “hard landing” for a Chinese economy that suddenly seemed to be in a free fall.

Both camps recognized the bad economic news was a threat to the Party itself and so agreed to work together.

Martial Law

The agreement, though, did not change the basic situation facing Jiang’s faction. Zhou Yongkang, Propaganda Minister Li Changchun, and others in Jiang’s faction could not face losing power.

If the Party were led by Xi, who was not heavily implicated in the persecution of Falun Gong, he could end it. Once the persecution was ended, the pressure for holding those accountable for the crimes committed during the persecution would be immense.

Millions of Chinese have been tortured and subjected to brainwashing. The Falun Dafa Information Center can confirm over 3,500 Falun Gong practitioners killed from the abuse, but acknowledges the actual number is in the tens of thousands. Many more have been gravely injured.

According to the research done by former Canadian Secretary of State (Asia-Pacific) David Kilgour and Canadian human rights lawyer David Matas, in the years 2000-2005, 41,000 practitioners were likely murdered through forced, live organ harvesting. According to Matas, each year since an estimated 8,000 practitioners are murdered through organ harvesting, which means the total number now approaches 100,000. A generation of orphans had been created; families across China were broken; careers and livelihoods destroyed; homes lost.

In order to avoid being held accountable for the atrocities, Jiang’s faction knew they had to keep a tight grip on power. After the Jingxi meeting, the leaders of the faction met frequently, discussed matters, and bided their time.

With the revival of the controversy over the Diaoyu Islands, the faction saw its chance.

That summer, boats meant to take Chinese on the mission of reclaiming the islands had several times been turned back by the Chinese regime.

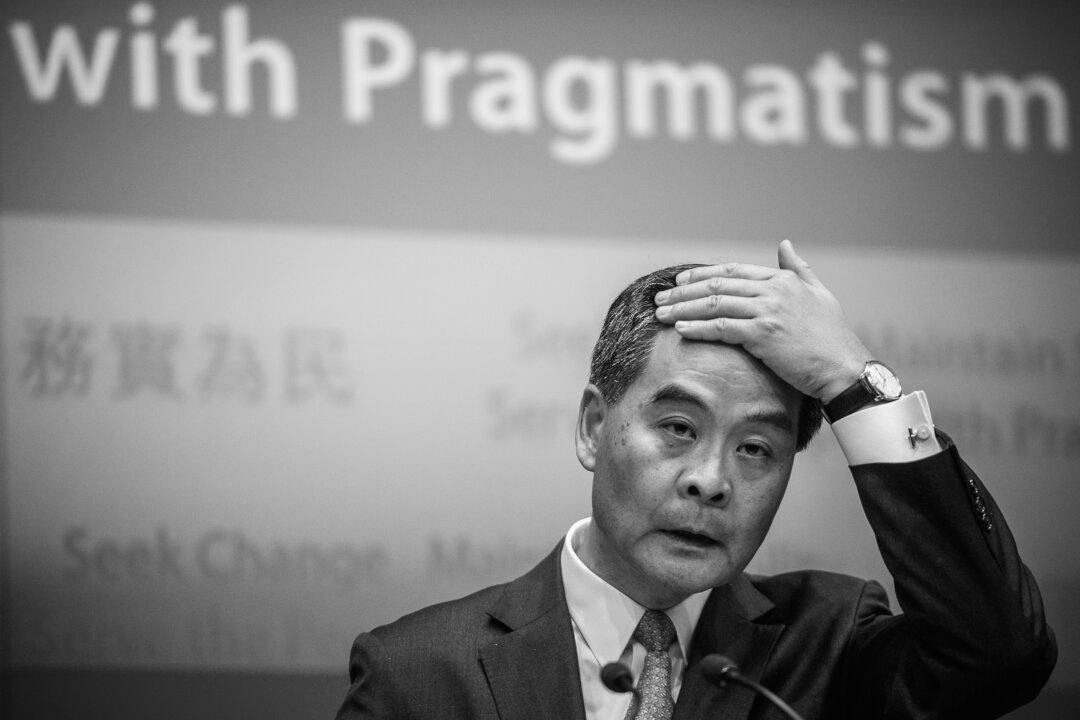

The Aug. 15 landing was allowed to go ahead by Hong Kong chief executive Leung Chung-ying, who, working with the United Front Work Department, had arranged for Hong Kong fishing vessels to make the sortie.

Leung was a protégé of Zeng Qinghong, who had long been one of Jiang Zemin’s closest allies. Zeng, a former Politburo Standing Committee member and current head of the National People’s Congress, had long held the portfolio for Hong Kong.

The United Front Work Department is responsible for making alliances with organizations not known to be affiliated with the CCP and working with them to attack the CCP’s enemies. It also controls a wide-ranging network of spies.

The United Front Department was the last Party institution still controlled by the Jiang faction and was headed up by Jiang loyalist Du Qinglin.

The United Front used Chinese media based outside China to raise the temperature on the Diaoyu Islands controversy, evoking nationalist emotions and demanding action.

The Jiang faction wanted to use mass protests to pressure Hu Jintao and Xi Jinping. By bringing China to the brink of war with Japan, the faction could then urge wartime preparations, which would include instituting martial law. The 18th Party Congress and the installation of new leadership would have to be delayed, and Zhou Yongkang and others could remain in power for an extended period of time.

An information war added to the pressure. At the end of August, the Jiang faction used its United Front contacts to spread worldwide the rumor that Hu Jintao would give up control of the military after the 18th Party Congress, increasing the sense of events being out of control.

Zeng Qinghong circulated privately among CCP officials, making the argument that the Party had to turn to martial law to handle the Diaoyu Island and economic crises.

Events inside Hong Kong added to the pressure on Hu, Wen, and Xi.

Leung Chun-ying, upon his assuming office on June 30, had immediately begun promoting the National Education plan. This curriculum is regarded in Hong Kong as an attempt at brainwashing the city’s children, and sparked weeks of huge protests in Hong Kong.

The promotion of the National Education plan was meant to irritate the Hong Kong people, cause unrest in Hong Kong, and make trouble for Hu and Wen before the Party Congress.

When Gu Kailai was given a suspended sentence on Aug. 20 for the murder of the British businessman Neil Heywood, United Front spies began planting stories worldwide in order to de-legitimize her trial and any discipline intended for Bo.

Information was released that the defendant who appeared at the Gu Kailai trial was not her, but a body double. A story was planted that the Gu Kailai trial had been “kidnapped” by Bo’s enemies and was being used as part of the effort to destroy him.

The rumor was also spread that Zhou Yongkang would help Bo Xilai to reverse the original verdict and get a new trial for Gu.

Chinese-language websites outside China quoted one of Zhou’s “trusted aides” on Sept. 3 as saying, that Zhou Yongkang has said privately many times that Gu Kailai did not murder Heywood.

The trusted aide also said that Zhou Yongkang visited Bo Xilai and Gu Kailai quite a few times in the last few months. Zhou Yongkang is reported to have said that Bo Xilai believes that the darkness will pass quickly, and he definitely will see the sunrise.

Counter Attack

On Aug. 29, Air China flight CA981 was forced to make a midair emergency turnaround to Beijing after flying seven hours from Beijing to New York.

A source told The Epoch Times that a female spy named Ms. Ding, who works for the United Front Work Department, was arrested after the flight landed in Beijing, and Hu Jintao personally ordered the flight’s return.

On Sept. 1, the CCP announced three major personnel changes in one day, a highly unusual occurrence.

Du Qinglin was suddenly retired from his post as director of United Front. Du was replaced by Ling Jihua, Hu Jintao’s trusted chief of staff who had managed the work of taking down Bo Xilai’s cronies. Li Zhanshu, a stalwart of Hu’s Communist Youth League faction and said to be close to Xi Jinping, succeeded Ling as the director of the CCP’s general staff.

On Sept. 5, Xinhua announced that Wang Lijun would be tried.

Also on Sept. 5, Hu Jintao forbade Leung Chun-ying from going to Russia to participate in the APEC meeting. This made the new chief executive of Hong Kong look very bad internationally, by showing how much CCP officials distrusted Leung. This act also signaled to the Hong Kong people that Leung had not been following Hu or Wen’s orders.

On Sept. 9, Leung announced the National Education plan was being withdrawn in Hong Kong.

The actions of Jiang’s faction had put the backs of Xi Jinping and his camp against the wall.

Xi could see clearly that if events were allowed to continue as they had been going, he and those loyal to him would be criticized inside and outside of the CCP. Having no way to retreat, Hu Jintao and Xi Jinping had come together to attack.

Xi’s Bad Back

At the same time that Hu Jintao and Xi Jinping began striking back at the Jiang faction, Xi asked to be let out of becoming the next chair of the CCP.

At a Politburo meeting at the end of August, Xi said he was only willing to be a member of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party and to participate in the building and development of the Party. This shocked everyone in the Party compound of Zhongnanhai and anyone else who knew about it.

On Sept. 4, Xi cancelled a meeting with U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and dropped out of sight, and the entire world began speculating as to what was happening.

Xi had been originally chosen because he was acceptable to both sides. There was no one to replace him, and if Xi did step down, both factions thought the CCP would immediately collapse.

Party elders emerged and attempted to mediate. Qiao Shi, Li Ruihuai, Zhu Rongji and the very powerful family of Ye Xuanning all reached an agreement and expressed their support for Xi.

During the 14 days of Xi’s disappearance from public view, a new consensus was reached within the Party: the 18th Party Congress would convene on Nov. 8; Bo Xilai’s political life was over; the Party would systematically eliminate the residual influences of the Great Cultural Revolution and gradually discard Mao Zedong Thought, Marxism-Leninism, and so on.

On Sept. 19, Tung Chee-hwa, the former Hong Kong chief executive, unexpectedly gave an interview to CNN.

Tung said Xi Jinping had injured his back while swimming, which caused him to disappear for two weeks from the public eye. In addition, Mr. Tung also casually mentioned the common sense view that Mr. Xi would certainly become the next Party head.

Bo Xilai’s Shadow

Since Bo Xilai’s former deputy mayor, police chief, and henchman Wang Lijun fled to the U.S. Consulate in Chengdu on Feb. 6, the CCP leadership has faced an increasingly narrow set of options.

Exposing the atrocities committed by the Jiang Zemin faction will bring the Party into such discredit with the Chinese people, it will lose the ability to govern.

Not exposing the atrocities of the Jiang faction allows it to remain politically viable. Jiang’s faction knows that if it loses power, the faction may be charged with terrible crimes. It can only protect itself by seizing power.

But if Jiang’s faction were allowed to continue in power, any hopes for reform in China would end. With popular discontent growing daily, a failure to reform also means a likely end to the Party.

At the Jingxi Hotel in May, Hu Jintao tried to equivocate: the Jiang faction would be let off the hook in return for factional infighting ending and the beginning of political reform.

But summer saw yet another attempt by the Jiang faction to hold onto power and to threaten Hu and Xi.

In the first two weeks of September in the wake of Xi’s attempt to resign, the Party chose to move forward on Bo Xilai’s case. The concern, once again, was to find a way to save the Party.

The reaction to Xinhua’s announcement on Sept. 28 that Bo will basically be charged for corruption has shown how fragile the new Party consensus really is.

Provincial officials did not, as they had done when Bo was removed from the Chongqing Party Committee on March 15 or from the Politburo on April 10, show “enthusiastic support for the CCP Central Committee.”

The crimes Bo is charged with are common among CCP officials. Many could easily be charged as Bo has been. Moreover, charges of corruption will not of themselves end Bo’s political career. They leave open the possibility of a comeback.

At the same time, charging Bo without eliminating the faction that supports him makes possible that in the future, Hu Jintao, Wen Jiabao, and Xi Jinping may in turn be charged for “mishandling” Bo’s case.

After the 18th National Congress, if Xi Jinping still seems to be in the minority and is unable to dispose of his political opponents, local officials may protect themselves by hesitating to express allegiance to him.

The Maoists in the Party have not gone away. In the mass anti-Japan demonstrations in mid-September, the slogan “Bo Xilai Belongs to the People” was once again prominently displayed.

Just as members of Jiang’s faction are forced by the logic of their situation to try to hold onto power for the sake of their own survival, so Xi Jinping may find that his survival depends on holding that faction accountable for its crimes.

The Epoch Times publishes in 35 countries and in 19 languages. Subscribe to our e-newsletter.

Editor’s Note: When Chongqing’s former top cop, Wang Lijun, fled for his life to the U.S. Consulate in Chengdu on Feb. 6, he set in motion a political storm that has not subsided. The battle behind the scenes turns on what stance officials take toward the persecution of Falun Gong. The faction with bloody hands—the officials former CCP head Jiang Zemin promoted in order to carry out the persecution—is seeking to avoid accountability for their crimes and to continue the campaign. Other officials are refusing any longer to participate in the persecution. Events present a clear choice to the officials and citizens of China, as well as people around the world: either support or oppose the persecution of Falun Gong. History will record the choice each person makes.

Click www.ept.ms/ccp-crisis to read about the most recent developments in the ongoing crisis within the Chinese communist regime. In this special topic, we provide readers with the necessary context to understand the situation. Get the RSS feed. Who are the Major Players? ![]()