Eber Upton, a professor at the University of Cambridge in the U.K. found that only a small number of children were interested in studying computer science. The number was getting lower year after year year, and the kids that did come knew little about computer hardware and programming. He figured out that the computers in their homes were relatively expensive, and tinkering with the machines would have been prohibited by the parents.

Upton and his colleagues invented a solution, a cheap computer that nearly any kid could afford using pocket money, that would be used mainly for programming, that could be used to equip a whole classroom in a very cost-effective way. What they did not anticipate was the huge, almost fanatical response the device received from all over the world. He name the device “Raspberry Pi,” kicking off a revolution in computer programming.

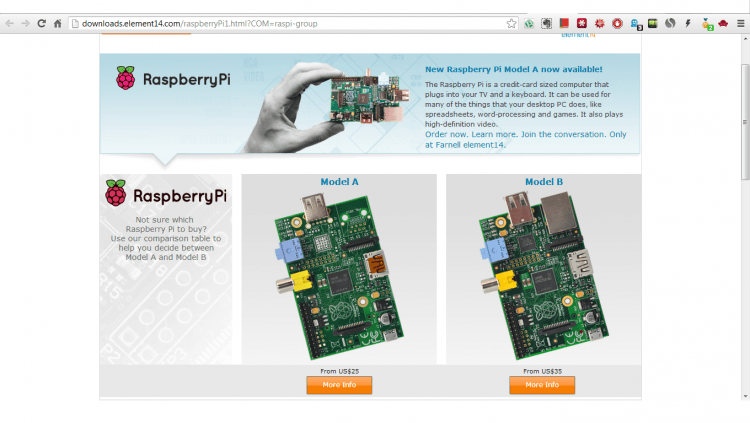

The Pi could be among the world’s smallest computers, measuring just 3.3 inches by 2.1 inches—as small as a credit card. Depending on the model (there are currently two: model A and model B), there is an Ethernet controller, USB port, HDMI video output, built-in memory (256mb for model A, 512mb for model B), and a micro-USB for power. The processor and graphics are integrated. Model A, with one USB and no Ethernet, costs just $25, while model B cost $35.

Of course, the minimal design has no casing and does not support an on/off switch. To switch it off, you could simply pull the power cable. When you order Raspberry Pi, all you get is a tiny board. The OS and other programs need to be be loaded into a SD card that needs to be purchased separately.

The Raspberry Pi can be used to browse the Web, watch movies connected to the TV through the Internet, play games, and obviously, for computer programming. While primarily intended for school children, the device has found hardcore following of technically literate adults who want to use it for interesting projects. Some of the various uses people have found for the Raspberry Pi include robotics, making supercomputers (through clustering several Raspberry Pis together), making arcade cabinets for gaming, sending images from near space, setting up home automation systems (using Siri), and pairing a Raspberry Pi with a touch screen to build a tablet PC. Yet, don’t expect the device to multi-task memory intensive applications like your normal PC.

In reply to CNN’s question about the kind of reaction the Pi received from schools, Upton said, “We were really surprised by the reaction we got. School kids today are used to their tablets and their mobile phones, so we thought we were going to have to put into a shiny box. But one of the biggest reactions from the children was because they could actually see it and point to it and tell what the different bits do. Normally you don’t get to see the green stuff and they really love that, there’s been such a positive response.” Almost 1 million of these $35-machines have shipped since last February.

You can’t buy the Raspberry Pi from a computer store yet. Currently, the devices are sold online by RS Electronics, Allied Electronics and Element 14/Premier Farnell.

The Pi has re-kindled imaginations of kids and adults around the world, experimenting and exploring the possibilities of the device. It has not only reached kids in the developed world, but people from all around the world can now afford and access the hardware and be part of a vibrant community of Pi enthusiasts.

Upton, with his colleagues, has formed a charity organization, the Raspberry Pi Foundation, with the aim to create and launch a computer that is so affordable that every child in Britain can get one. And that goal, it seems, has been fulfilled.