The population of the European Union has reached 500 million people—more than the United States, Canada, and Mexico combined. According to a recent study, the EU is bulking up due to a combination of migration and natural population growth.

Dr. Sergei Scherbov, lead researcher of the joint study between the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) and the Vienna Institute of Demography, says that about 1 million to 1.5 million people are moving to the EU every year. The bulk come from places like Turkey, Eastern Europe, Africa, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and the Caribbean.

“If there was no migration, there would be no growth,” says Scherbov.

However, Scherbov says that migration in the EU over the last year has been stagnant due to the economic crisis. He expects that as the economy stabilizes, many immigrants will return to their countries, which has already started to happen.

The immigration nonetheless, adds to the diversity and complexity of the old continent.

While we now consider the EU as a collective unit, the fact is, the political alliance is far from a monolithic block.

For 50 years during the Cold War, many now EU countries were on opposite sides of the Iron Curtain, with the NATO alliance in the West, and the Warsaw Pact countries under communist rule in the East.

This division crumbled in 1989 with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the new epoch truly began in 1993, with the establishment of the EU.

Today, the EU is comprised of 27 countries, with even more cultures, and 23 official languages. As the union enlarges and membership grows, the number of countries, languages, and of course complexities, will increase as well.

“In some European countries like the U.K., France, and Sweden, the fertility rate is pretty high these days, much higher than it is in China. It is not only due to immigrants, but also a very strong social policy, which allows women to combine childbearing with activeness in the labor force,” says Scherbov.

Scherbov adds there is a demographic theory that in countries where men share responsibility with women for child-raising and taking care of the family, fertility is expected to rise. The theory plays out in Scandinavian countries where there is greater gender equality.

In terms of demography, European countries can be divided by life expectancy. Scherbov says there is a clear distinction between Western Europe and Eastern Europe.

“Eastern European countries have much lower life expectancy than in Western Europe. For example, in Russia, for males it is 61.5 years, for females 74.2 years. For females in France the life duration is almost 85; for males in Iceland the life expectancy is about 80.

“In Russia, for example, people are poisoned by drinking alcohol, there is a lot of stress, and environmental factors. It is similar in Ukraine and former Soviet countries. In Western European countries people have a very different attitude toward life.”

Scherbov says that the claims that Europe has an aging population is no longer fact. According to the study, aging is slowing down, with the progressive increase of life expectancy. The term “old” is changing its meaning too.

“Our assumptions are that life expectancy will grow by two years per decade. This has been a historical trend for the last 60 years, especially in Western European countries.”

The scientist notes that 200 years ago few people would survive 65, but now 95 percent of the people survive to this age. And this gives a very good reason for governments to think of an increase in the age of retirement.

This is one of the tools some EU countries have used to help engineer an exit from the economic crisis. France is set to raise the age of retirement from 60 to 62, Germany bumped it from 65 to 67, and Greece is being pressured to do the same.

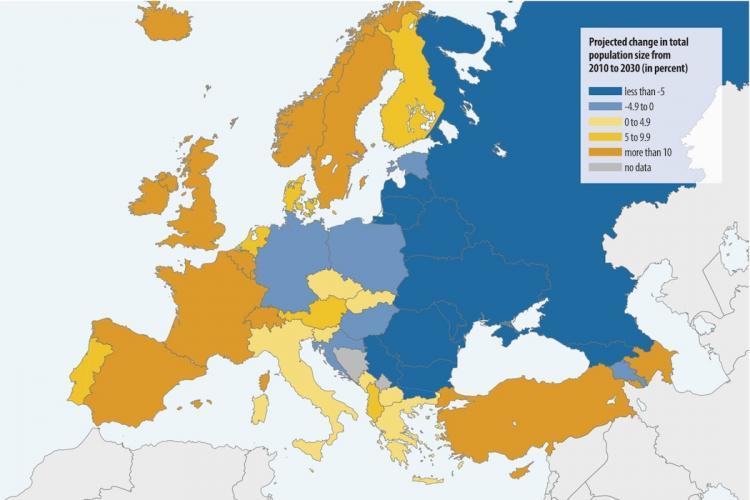

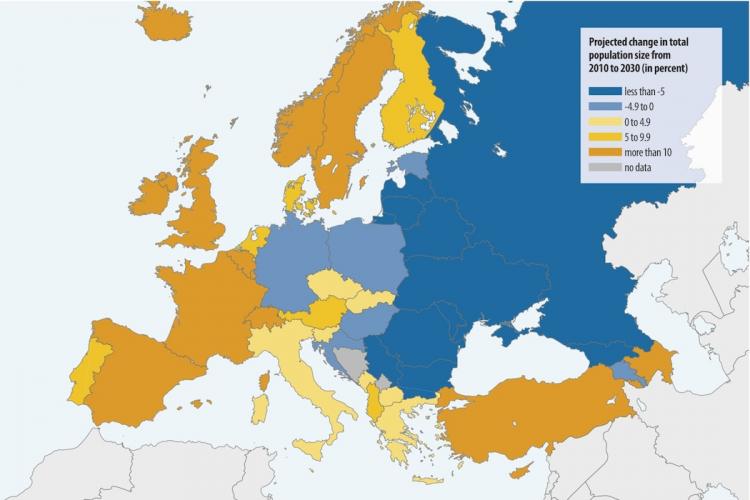

The research predicts that by 2030, the EU’s population will top 528 million.

Dr. Sergei Scherbov, lead researcher of the joint study between the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) and the Vienna Institute of Demography, says that about 1 million to 1.5 million people are moving to the EU every year. The bulk come from places like Turkey, Eastern Europe, Africa, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and the Caribbean.

“If there was no migration, there would be no growth,” says Scherbov.

However, Scherbov says that migration in the EU over the last year has been stagnant due to the economic crisis. He expects that as the economy stabilizes, many immigrants will return to their countries, which has already started to happen.

The immigration nonetheless, adds to the diversity and complexity of the old continent.

While we now consider the EU as a collective unit, the fact is, the political alliance is far from a monolithic block.

For 50 years during the Cold War, many now EU countries were on opposite sides of the Iron Curtain, with the NATO alliance in the West, and the Warsaw Pact countries under communist rule in the East.

This division crumbled in 1989 with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the new epoch truly began in 1993, with the establishment of the EU.

Today, the EU is comprised of 27 countries, with even more cultures, and 23 official languages. As the union enlarges and membership grows, the number of countries, languages, and of course complexities, will increase as well.

Living Longer

In addition to migration, Scherbov sites high fertility rates and longer life expectancies as other important factors in the EU’s expansion.

“In some European countries like the U.K., France, and Sweden, the fertility rate is pretty high these days, much higher than it is in China. It is not only due to immigrants, but also a very strong social policy, which allows women to combine childbearing with activeness in the labor force,” says Scherbov.

Scherbov adds there is a demographic theory that in countries where men share responsibility with women for child-raising and taking care of the family, fertility is expected to rise. The theory plays out in Scandinavian countries where there is greater gender equality.

In terms of demography, European countries can be divided by life expectancy. Scherbov says there is a clear distinction between Western Europe and Eastern Europe.

“Eastern European countries have much lower life expectancy than in Western Europe. For example, in Russia, for males it is 61.5 years, for females 74.2 years. For females in France the life duration is almost 85; for males in Iceland the life expectancy is about 80.

“In Russia, for example, people are poisoned by drinking alcohol, there is a lot of stress, and environmental factors. It is similar in Ukraine and former Soviet countries. In Western European countries people have a very different attitude toward life.”

Scherbov says that the claims that Europe has an aging population is no longer fact. According to the study, aging is slowing down, with the progressive increase of life expectancy. The term “old” is changing its meaning too.

“Our assumptions are that life expectancy will grow by two years per decade. This has been a historical trend for the last 60 years, especially in Western European countries.”

The scientist notes that 200 years ago few people would survive 65, but now 95 percent of the people survive to this age. And this gives a very good reason for governments to think of an increase in the age of retirement.

This is one of the tools some EU countries have used to help engineer an exit from the economic crisis. France is set to raise the age of retirement from 60 to 62, Germany bumped it from 65 to 67, and Greece is being pressured to do the same.

The research predicts that by 2030, the EU’s population will top 528 million.