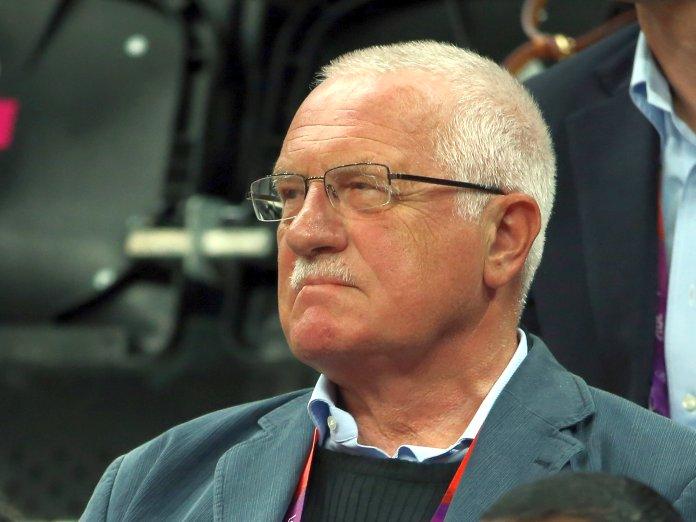

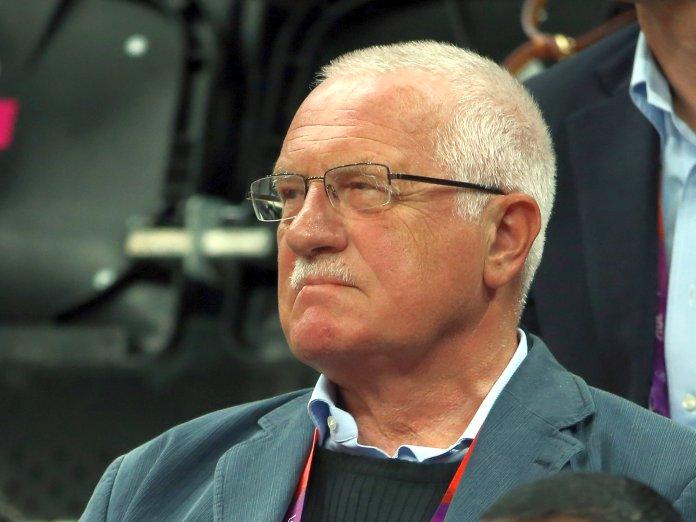

NEW YORK—Czech President Vaclav Klaus pulled no punches in his analysis of the European debt crisis Monday, predicting a breakup of the euro currency union, whose failure he describes as “inevitable.”

Klaus, an economist by trade, spoke at an event organized by Hunter College and the Hudson Institute to introduce his new book “Europe: A Shattering of Illusions” to the United States. He has always been a eurosceptic, a category of intellectuals who tend to be brushed-off as “anti-Europe” and “populist” by most of the mainstream media on the other side of the Atlantic.

Klaus has a distinguished history in his fight against communism, having been part of the Velvet Revolution in 1989. He also embraced free-market economics during communist rule and used to distribute the banned writings of Milton Friedman in what was then Czechoslovakia.

It is this background of living for free markets and democracy against the backdrop of an authoritarian regime that gives him an angle that most other European politicians lack. His service record as the minister of finance of Czechoslovakia as well as prime minister and president of the Czech Republic give him the stature to utter such grave concerns in a rational manner.

Heterogeneous Economies Need Adjustment Through Currency Revaluation

When speaking about the economic problems within the eurozone to The Epoch Times, Klaus made it clear that there is no solution “inside the euro framework,” and that “all kinds of fixed exchange rate regimes sooner or later collapse.”

He previously conducted a study in which he examined the exchange rate revaluations in the eurozone before the euro was launched in 1999. He found that countries such as Spain, Italy “and even France” were in a constant process of devaluing their currencies from 1963 to 1998 to keep up with German competitiveness, some of them losing 85 percent of their value over time.

Given the structural differences in the diverse economies of Europe, Klaus believes that “some exchange rate realignments must happen,” as European countries failed to reciprocate the intercountry liberalization of markets after World War II on an intracountry basis as well.

In his speech, he criticized the European Union’s “almost communist type of reasoning,” meaning that Brussels believes that “politics may dictate economics.”

He thinks the euro is the prime example of this ideology: “How can anyone advocate that overnight from the first of January 1999 everything would have changed and such a process wouldn’t be necessary. The same process continues, … just being inside, imprisoned inside the one exchange rate, one interest rate one monetary policy, I don’t think it’s feasible.”

Internal Devaluation Does Not Work

Austerity proponents of the euro such as German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble often cite the possibility of weaker eurozone countries reforming their economies and becoming more competitive through internal devaluation. This process would see a reduction in unit labor costs in the periphery to more or less match German standards.

Klaus, however, does not think this is possible in practice: “The so-called internal devaluation of wages and salaries and domestic prices is of course theoretically possible. … You can make a nice economic model showing that, but in reality we all know that there is a downward wage rigidity, which is not just a specific issue, but a permanent situation in the world,” he said, adding that the political economy of Spain or Greece would not allow for this adjustment to happen.

This stance of a competitive system within the context of independent states, which manage their own currencies is not surprising, given his own background in the study of economics, which he studied at Prague and Cornell University.

Klaus said that he first had to break free of Marxist theories he studied 55 years ago. “The real paradigm shift was moving from Marxist political economy for my generation to the standard, mainstream economic theory. … The second stage was now to discuss whether you are more a Keynesian or a monetarist, of whether you are more micro or macro. ... In this respect I moved to monetarism, definitely not Keynesianism, to the Austrian school in some respect, to the public choice school and so on.”

Czechoslovakia’s Currency Union Easy to Dismantle

Rather than just criticize, Klaus also offers suggestions for Europe to solve the crisis, as an outcome of “political debates in individual EU member countries. It must be generated by the people, the ‘demos’ of these countries,” rather than undemocratic decrees from Brussels, in what he calls a “paradigm shift” in thinking about Europe.

When asked about Greece and a specific progression of events, he declined to provide further detail, but he did mention in his speech, “Some states must be left to fall.”

He thinks that the sunk costs of the union are “already here” and “muddling through” will only delay the inevitable and make it more expensive. Ultimately, he only foresees one possible solution and that is returning to a federation of states, rather a fully unified Europe—without the euro in its current format.

As the last finance minister of a unified Czechoslovakia, Klaus is perhaps the only Politian who has experience in dissolving a currency union. “Czechoslovakia was a political union, Czechoslovakia was a fiscal union … and Czechoslovakia was a monetary union. … Our experience was that simply it was not possible to keep the political and fiscal union together, but we had some dreams, similar dreams as in Europe these days. … Maybe it would be possible to keep the monetary union.” He recalls the process that led to the creation of the Czech Republic and Slovakia on Jan. 1, 1993, highlighting the remarkable similarity to Europe today, which also runs a monetary union without a fiscal union.

He further explains that this particular example of the dissolution of a currency union was relatively quick and painless. “The split of the currency was a nonevent and we continued the next morning as if nothing happened. In some respect we had similar experiences, the Slovaks were afraid of the developments in Slovakia, so many brought their savings into Czech banks, so this is something similar what you see in Greece and Germany. It was really, really technically possible to do it.”

Arguably, dissolving a block of 17 member states would be more complicated, but Klaus thinks it is all a question of how to go about it: “The issue is to make it as a preorganized process, not to let it go to the point when the anarchic process would dominate and create many problems and troubles.”

The Epoch Times publishes in 35 countries and in 19 languages. Subscribe to our e-newsletter.