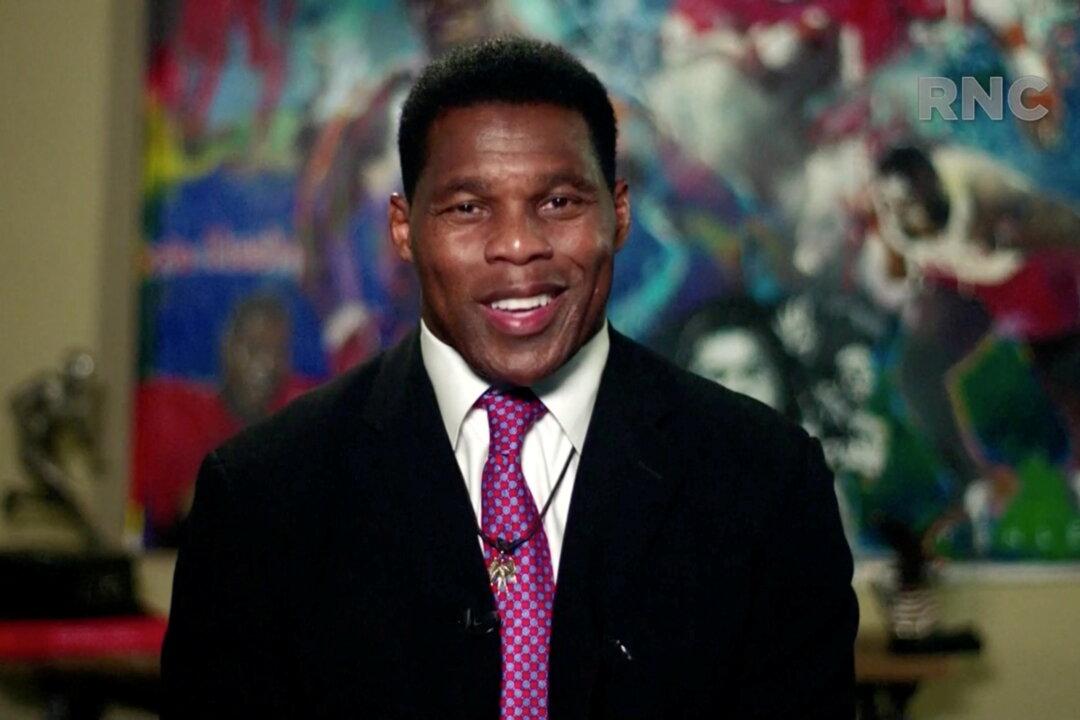

He’s not very polished, but Herschel Walker speaks to a crowd with a lot of conviction and drive. He takes the positions you expect a Republican to take, but finds the roots and reasons in his own life story.

He talks about growing up poor in Wrightsville, Georgia. He talks about picking peas and cotton, and thinking that baling hay was a step up; a better job. He talks about the hard work that made him a Heisman Trophy winner as he led the Georgia Bulldogs to a national championship.