Guo De-Huang’s wife tried to convince him not to go to the Appeals Office in Beijing on April 25, 1999. She feared for his safety. But a fellow Falun Gong practitioner from Tianjin had asked for his help on April 24, and he felt it was his duty to go. “We have to do something, show our support. In my mind I’m thinking we are one body.”

He did not know this would be a watershed in his life. In Tianjin, a relatively small city, a few practitioners had been badly beaten at an exercise practice site, and some had been detained. Suddenly, the winds of the political climate seemed to be turning against Falun Gong, the meditation practice that had been growing in the 1990s to the point of 70 million or more practitioners.

The practitioner from Tianjin said the local police had advised him that the problem could only be resolved through the authorities in Beijing. They told him he must go there personally to get the others released. Dr. Guo explained the hierarchy—that in China, smaller cities are governed by larger cities. Zhongnanhai is the seat of the regime in Beijing, similar to the U.S. government’s White House. That is where 10,000 Falun Gong practitioners quietly went to appeal for the release of their fellows on April 25.

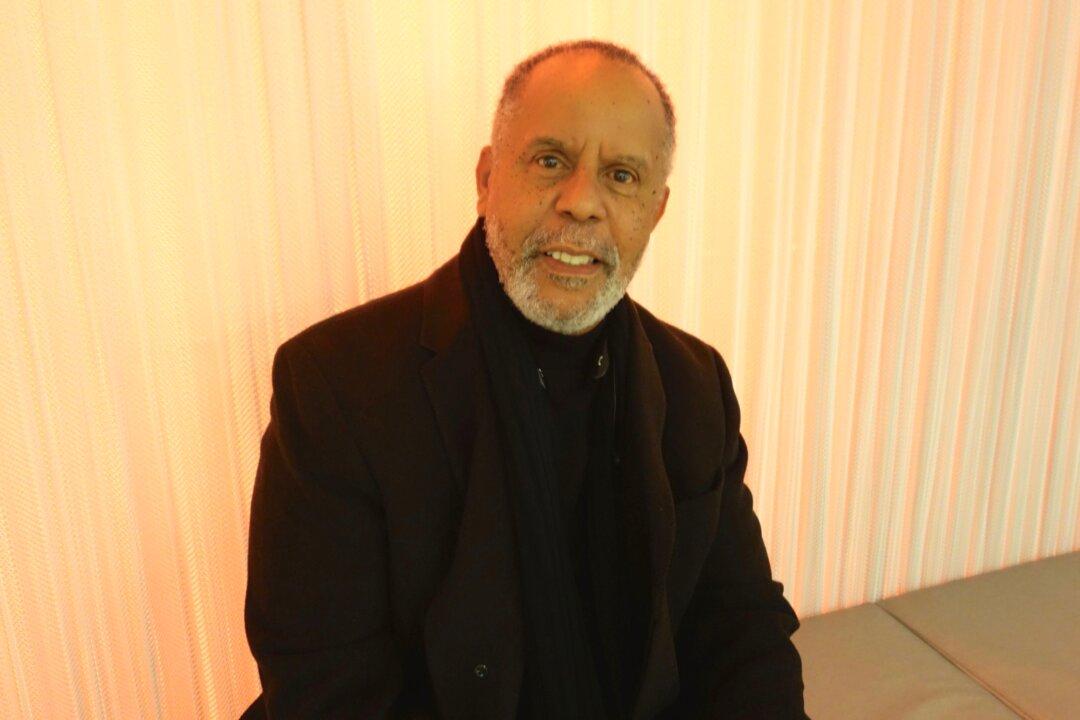

Dr. Guo worked as a medical researcher for a military work unit, one hour from the Appeals Office. He got on the subway before dawn, but when he got there, the street was full of people quietly waiting in line. He said he kept walking up and down, curious, and hoping to find a friend to stand with. “Some began to take packets of small cakes. Here some reminded us, ‘don’t throw any trash, because this is a beautiful street.’”

The people carefully followed the directions of the police, said Dr. Guo. The police began to joke about how easy and peaceful the event was. He saw some people in army uniforms waiting in the lines. “Later I knew those in uniform were in big trouble because they are easy to identify. ... I want to remind you, before people got in line, police went before us, guiding us, guiding all our team, where to go.”

“In the afternoon we heard someone say Premiere Zhou came and met with some practitioners,” Dr. Guo recounted. Around 8:30 or 9:00 p.m. he heard that the regime had agreed to release the Tianjin practitioners. “I felt happy,” Dr. Guo said. The enormous group went home. It has been called the largest assembly since the Tiananmen Square events in 1989.

Pressure built, later, however. He knew things were serious when his bosses’ boss came to talk to him, telling him he needed reeducation and to say who made him go. He needed to apologize. “The emperor says that a deer is a horse,” he said. Jiang Zemin, the leader of China at that time, wanted to force people to renounce Falun Gong. A few years before, the Communist Party was lauding the practice for its health benefits and subsequent savings on health care for the nation.

But his boss would not ask him to renounce. “My boss was very kind to me—he wanted to protect me,” said Dr. Guo. His boss used his connections to get Dr. Guo a passport in a week and borrowed $2,000 for him. Dr. Guo fled to Augusta, Ga., and is now a research scientist and lives in a nice house near the Master’s golf course with his wife and son. His wife “feels a little regret she did not go. She says it is one of history’s biggest events.”