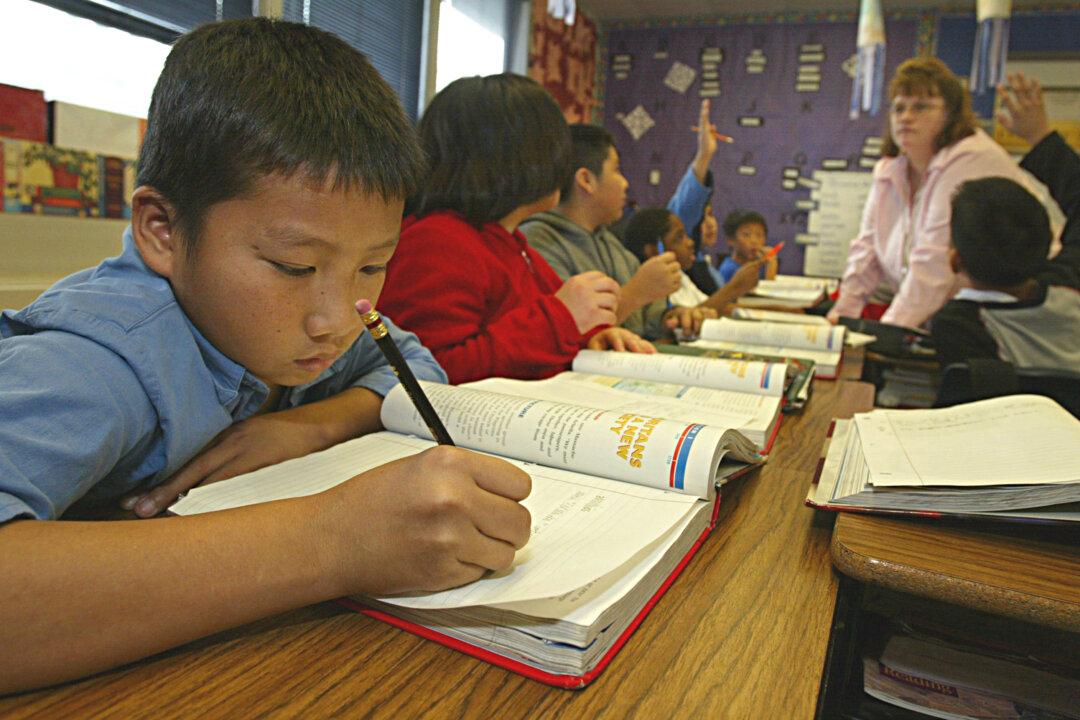

There has been much discussion in recent years about why East Asian children perform so well on international education tests. I’ve argued before that there is no one reason for these countries’ stellar results, but that home background and culture plays an important role.

In the UK, moves to introduce teaching methods popular in countries such as Singapore into the classroom have been heralded by politicians eager to replicate some of the successes of East Asian education systems.

We are beginning to see whether these borrowed methods are working in the classroom. My new study, which looked at a method called “Mathematics Mastery” that was introduced in primary and secondary schools in England, has shown a small impact on children’s progress in maths after one year.