Ninth-century hieroglyphs painted by a Mayan scribe in Guatemala are records of lunar and perhaps planetary cycles, forming the oldest known Mayan calendar.

The city of Xultún was discovered almost a century ago in the remote rainforest of the Petén region and covers 12 square miles. It was once home to many thousands of people, and monuments were constructed from the first centuries B.C. Only 56 structures have been counted and mapped among thousands more.

Led by William Saturno from Boston University, a team of archeologists has now excavated the calendar keeper’s room, which seems to be part of a house. This is the first time that Mayan paintings have been discovered on the walls of a house.

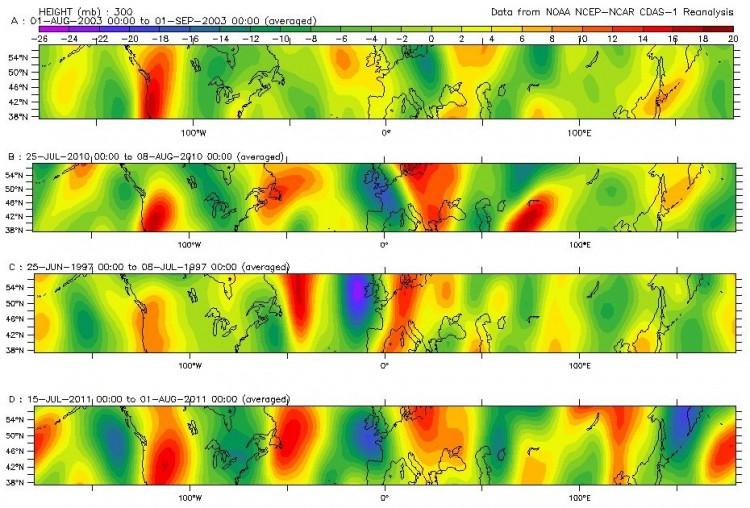

Despite damage by looters, numerous red and black glyphs, and various human figures are visible on the three intact walls. Calculations on the east wall refer to the lunar cycle, whereas the more obscure calculations on the north wall could be linked with Mars, Mercury, or Venus.

According to the researchers, Mayan calendars aimed to harmonize sacred rituals with celestial events.

“For the first time we get to see what may be actual records kept by a scribe, whose job was to be official record keeper of a Maya community,” said Saturno in a press release.

“It’s like an episode of TV’s ‘Big Bang Theory,’ a geek math problem and they’re painting it on the wall,” he added. “They seem to be using it like a blackboard.”

However, there is no indication that our world will end in 2012; rather, it will just enter another cycle.

“It’s like the odometer of a car, with the Maya calendar rolling over from the 120,000s to 130,000,” said study co-author Anthony Aveni at Colgate University in the release. “The car gets a step closer to the junkyard as the numbers turn over; the Maya just start over.”

The red and black calculations on one of the walls seem to represent the various calendrical cycles, ranging from the 260-day ceremonial calendar to the 780-day cycle of Mars.

“There are tiny glyphs all over the wall, bars and dots representing columns of numbers,” said decipherer David Stuart at the University of Texas–Austin in the release.

“It’s the kind of thing that only appears in one place—the Dresden Codex, which the Maya wrote many centuries later,” he continued. “We’ve never seen anything like it.”

The Mayan Codices were books written on bark paper a few centuries before Christopher Columbus landed in 1492.

When one enters the room, the north wall lies ahead, featuring a seated king adorned with blue feathers. Painted in bright orange, another man is carrying a pen, identifying him as the resident scribe, who may also have been the king’s son or younger brother.

“The portrait of the king implies a relationship between whoever lived in this space and the royal family,” Saturno explained.

Four long numbers on this wall show one-third of a million to 2.5 million days, stretching about 7,000 years into the future. These numbers seem to combine all the astronomical cycles important to the Maya, such as those of Mars, Venus, and lunar eclipses. Such a tabulation of all of these cycles has never been found before.

“The most exciting point is that we now see that the Maya were making such computations hundreds of years—and in places other than books—before they recorded them in the Codices,” Aveni said.

“The ancient Maya predicted the world would continue, that 7,000 years from now, things would be exactly like this,” Saturno said.

“We keep looking for endings. The Maya were looking for a guarantee that nothing would change,” he concluded. “It’s an entirely different mindset.”

The findings were published in Science on May 11 and will be discussed in the June issue of National Geographic magazine.

The Epoch Times publishes in 35 countries and in 19 languages. Subscribe to our e-newsletter