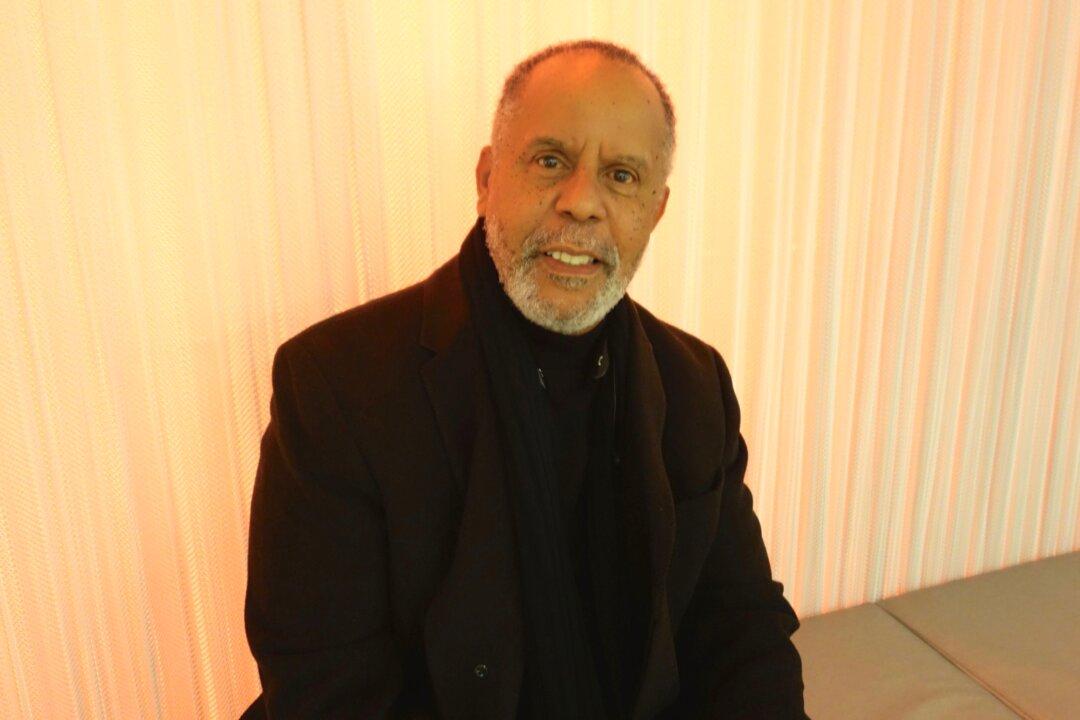

LITHONIA, Ga.—Dr. Lanier Phillips visited the Canadian village that changed his life one last time, a month before he died on March 12, at age 88. Though frail, he insisted on climbing the steep cliff where he survived the wreck of the USS Truxton, according to Wayde Rowsell, mayor of St. Lawrence, Newfoundland and Labrador.

“He was strong-willed, you know,” said Rowsell.

Phillips joined the Navy to escape the South, though even in the military African-Americans were then only allowed to be messmen—cooking and serving food. Growing up in segregated Georgia, he had known the cruelty of racism and bigotry. The Ku Klux Klan burned down his school. A man once slashed his mother’s and aunt’s tires, pushing their car off the road with a truck, when the two ran out of gas, according to his uncle, Louis Woodall.

“He never said anything bad about people. He was a crusader for justice, and that’s what I loved about him so much,” said Woodall. He described their childhood as a world of mules, penny candy, home fruit orchards, fishing holes, and men who would slash tires, “Just to do damage. ... The Ku Klux Klan was on the rage in that time.”

When the USS Truxton and the USS Pollux went aground in a snowstorm off Newfoundland in February 1942, the people of Lawn and St. Lawrence rescued Phillips and others. Violet Pike took him into her home and spoon-fed him. The kindness he experienced in Canada was a revelation, he said.

“Being rescued that day changed my life. And it wasn’t just being alive. ... It was the treatment I got from the people of that town. They treated me, for the first time in my life, just like they treated every other person rescued. ... They knew nothing about racism and segregation. They treated me like a person, a worthy human being, and for me, it was life-altering,” said Phillips, quoted on the official blog of the U.S. Navy.

From then on, the strong willed Phillips began his fight to be treated as a worthy human being. He desegregated the Navy, becoming the first African-American sonar technician.

From there, Phillips and Woodall marched and worked for civil rights and racial equality alongside the Rev. Martin Luther King.

After his naval career, he continued to work as a respected oceanographer, according to his son, Terry Phillips, who said his father was a model for lifelong learning.

“I remember watching him and his grandson do their homework together when he was in his 70s,” said Phillips. He took classes at MIT after he left the Navy and later studied real estate law in order to help his family handle problems with land titles.

Phillips, who is an attorney, said, “My father loved education. He always worked to improve his understanding of the world.”

The Navy man worked to improve other people’s understanding, too, traveling to tell his historic story, “even when he wasn’t up to it,” Phillips said.

Phillips traveled all over North America to tell his story, said Rowsell. Selflessly, he gave recognition and honor to others, including those who saved his life, said Lt. Jack Barrett, chaplain in the Canadian Navy.

Rowsell and Barrett journeyed 2,600 miles from Newfoundland and Labrador to pay their respects at the Lithonia, Ga., church Phillips attended as a child.

Dekalb County CEO Burrell Ellis said the legacy of “homeboy” Lanier Phillips lives on. “We’re proud to own him because of the way he served.”