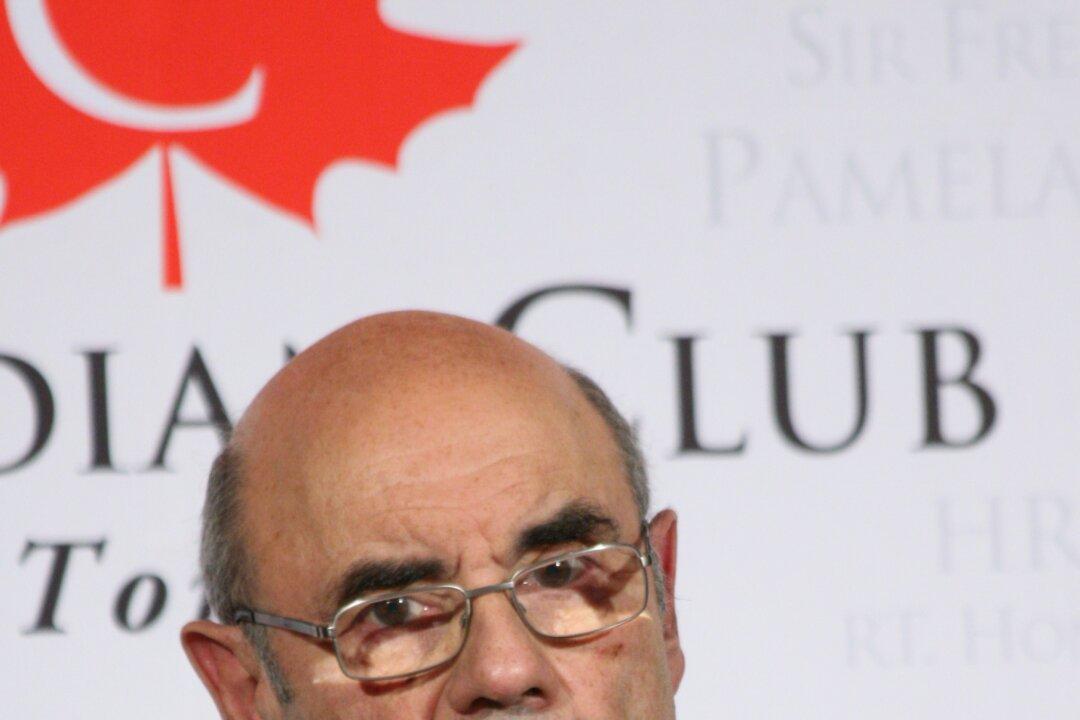

Where there are bridges to be built, problems to be solved, and potential to be realized, you will find Dr. Arnold Noyek, Canada’s pre-eminent ear, nose, and throat specialist and trailblazer extraordinaire.

Reading Noyek’s resume is humbling to say the least. The long lists of awards won, books authored, charities founded, and hospital appointments and professorships is a testament to the profound impact one man can have on the world.

This year Noyek was appointed an Officer of the Order of Canada, not only for his groundbreaking work to fight congenital deafness, but his ability to create global peace-building opportunities through medicine.

Noyek is the founder of CISEPO, the Canada International Scientific Exchange Program, whose mission is to build bridges to peace in the Middle East by fostering cooperative projects through academic and scientific exchanges among universities and medical centres.

These projects—such as getting Israeli and Palestinian medical students to volunteer together for children with cancer, or organizing a Jordanian and an Israeli to operate together on deaf twin boys broadcast on television—are not only transforming lives, but developing understanding between groups that are historically at odds.

“We'll just keep doing what we have to do to bring people together—people who normally would never take out the garbage together, let alone talk to each other—that’s been the vision,” Noyek said in an interview.

“The object of the game is to do good that links to Canadian values, ethics, and vision, but also to have fun in the process.”

Noyek chose ear, nose, and throat in med school because it was a “depressed” field at the time, and he wanted to help build it into a “world-class specialty.”

After graduating from the University of Toronto he worked primarily at Mount Sinai Hospital where he was Otolaryngologist-in-Chief from 1989-2002. It was there that he and his team developed a ground-breaking method to detect deafness in babies by measuring their brainwaves using an EEG.

The early screening procedure was adopted as provincial health policy in Ontario in 2001, and continues to spread across Canada and around the world. To date over one million babies have been screened.

Combining Two Passions

Noyek had been teaching and building relations in the Middle East since the early 1970s, but it wasn’t until the mid-‘90s that he discovered an extraordinary opportunity to combine his hearing program with his passion for uniting people.

In 1995 Noyek was approached by the late King Hussein of Jordan, who asked if he could help bring Arabs and Israelis together in the public health sector. The good doctor took up the challenge.

“What I wanted to look for in the health sector was common ground,” says Noyek. “At the end of the day [CISEPO] is a giant program about co-operation across cultures and faiths, and trying to go to higher levels.”

As Noyek started to build the program, he realized there was a great need for hearing loss screening in the Middle East, where genetic deafness is 6 – 10 times that of Western world due to intermarriage. By bringing Jordanians, Palestinians, and Israelis together through programs to address the issue, it created common bonds in the neutral territory of health—what he calls a “made in Canada” solution.

The result has been staggering: 800,000 babies screened in Jordan, 320,000 in Israel, 90,000 in Qatar. Next, his team aims to screen Palestinians across the West Bank. But it doesn’t stop there; the project has acted as a model, spawning many other partnerships that aim to build bridges through health-related sectors.

One of these programs is a cross-cultural exchange among Canadian, Israeli, and Palestinian medical students at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children. Many Israelis have never met a Palestinian and vice-versa, says Noyek, so it allows them to work together and build networks while practicing medicine and helping children.

“We started with building a network of peaceful professional co-operation, and that led to all sorts of advances on the world stage, not just in hearing health,” he says.

Today the 76-year-old is as active as ever: mentoring students, seeing patients, teaching at the University of Toronto and consulting on global projects. He has survived two cancers—one that briefly left him paraplegic—but he refused to let the disease win. “They said I‘d never walk again, and I said, ’No way!'”

Noyek says his drive and passion for helping others comes partly from being an only child and wanting to “make his parents smile,” but it is easy to conclude he was simply born with an inextinguishable kind and generous nature.

“I like happiness, and I think happiness is meant to be shared. Nothing makes me feel better,” he says.

“I have lived an extraordinary life, with extraordinary meaning, but I’ve done it because I have a wonderful team around me. You can’t do what I do and just do it as an individual.”