With France remaining economically stagnant, Italy falling back into recession, and Greece and Portugal still struggling to stand on their feet, the international community often looks to Germany, not only as the leader of the EU but also as the saviour of the Euro. It’s quite common to hear sermons on how the “south” of Europe should learn basic lessons of governance and public debt from their northern neighbours, with Germany at the head of that pack.

It’s not hard to see why: Germany has the highest GDP in the EU with $3.6 trillion, close to a trillion more than France, the next largest economy. The country also has the best GDP growth among the largest European economies including France and the UK. The country has also seen its GDP rise by over 8% since 2009 and 1.2m new jobs have been created. Indeed, in the last quarter of 2012, it even achieved a budget surplus of 0.4% of GDP. Like this was not enough, Germany is home to some of the leading companies in the world and a country that ranks high across spectra, from Global Competitiveness to Social Progress.

Germany also performs well on reducing unemployment, one of the great challenges of recent years given the so far intractable trend of joblessness around the world. With an unemployment rate at 5.2% in April this year, the country stands out as a notable exception in the EU and beyond, mirroring the golden performance of the US, prior to the meltdown of the financial crisis. But what’s more telling is youth unemployment. The jobless rate for those aged 15 to 24 is the lowest in the EU.

Dismantling the Perception

This constitutes some sound evidence of economic stability and health. But positive headline figures divert attention from a more realistic view of the country.

From Ostpolitik to Wandel durch Handel to Russlandversteher or even Putinversteher Germany has always sought closeness to Russia. Political considerations aside, Russia is an important trade partner: Russia is Germany’s eleventh biggest export market. On the other hand, Russia accounts for much of Germany’s gas, oil and coal imports.

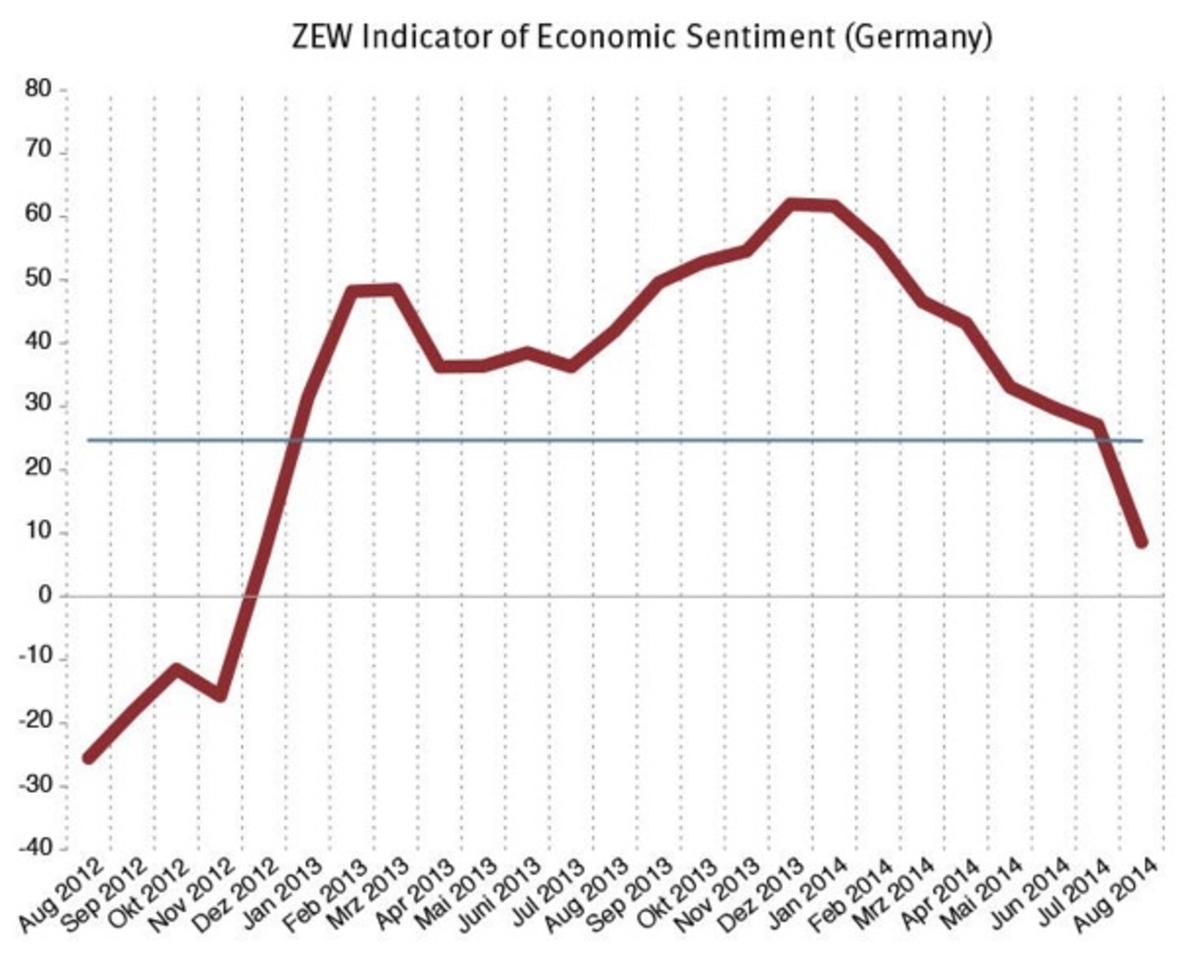

However, the sanctions imposed by the EU as a result of the conflict between Ukraine and Russia have started to hurt. The latest data shows that confidence among German investors took nose-dive in August, bringing Europe’s largest economy to a standstill (see the chart below).

ZEW Index

Sanctions have serious implications for German exports to Russia, but with confidence in decline (and at the consumer level too), the economic impact could become far greater. This has become immediately visible if we look at Germany’s unemployment rate at present, when unemployment rate has unexpectedly gone up in May. If we look at wages, then they have not been increasing enough to sustain the level of economic activity. Germany is, effectively, teetering on the edge of recession.

Also to bear in mind that Germany’s economic prosperity is, or at least has been, its export strength. Yet, the weakness in the euro thanks to the on-going Eurozone crisis has also made German exports cheap, and attractive to international buyers and therefore competitive. In the same words of the European Commission, Germany needs to reduce its “excessive export surpluses, which are hurting other European countries”.

So contrary to what the perception may indicate, the country’s strong exports actually highlight a weakness rather than a strength: the country is far from investing enough. The country’s current investment levels represent only 17% of its GDP; even countries in more difficult economic environments such as France and Italy are investing more. Public spending on infrastructure and other similar projects is a paltry 1.5% of GDP. The result is chronic under-investment in energy supply, transport infrastructure and education. Let’s delve deeper into education. With spending at about 5.3% of GDP, it is lower than both average of 15 European countries and OECD average of 6.2%; the investment gap is particularly big in early childhood education where prospective returns on education are especially high.

So, why is Germany not spending? A partial reason is that the country is practising what it preaches to other members of the Eurozone – the need to keep the fiscal budget tight even though it could hurt in a longer run.

Future Proof

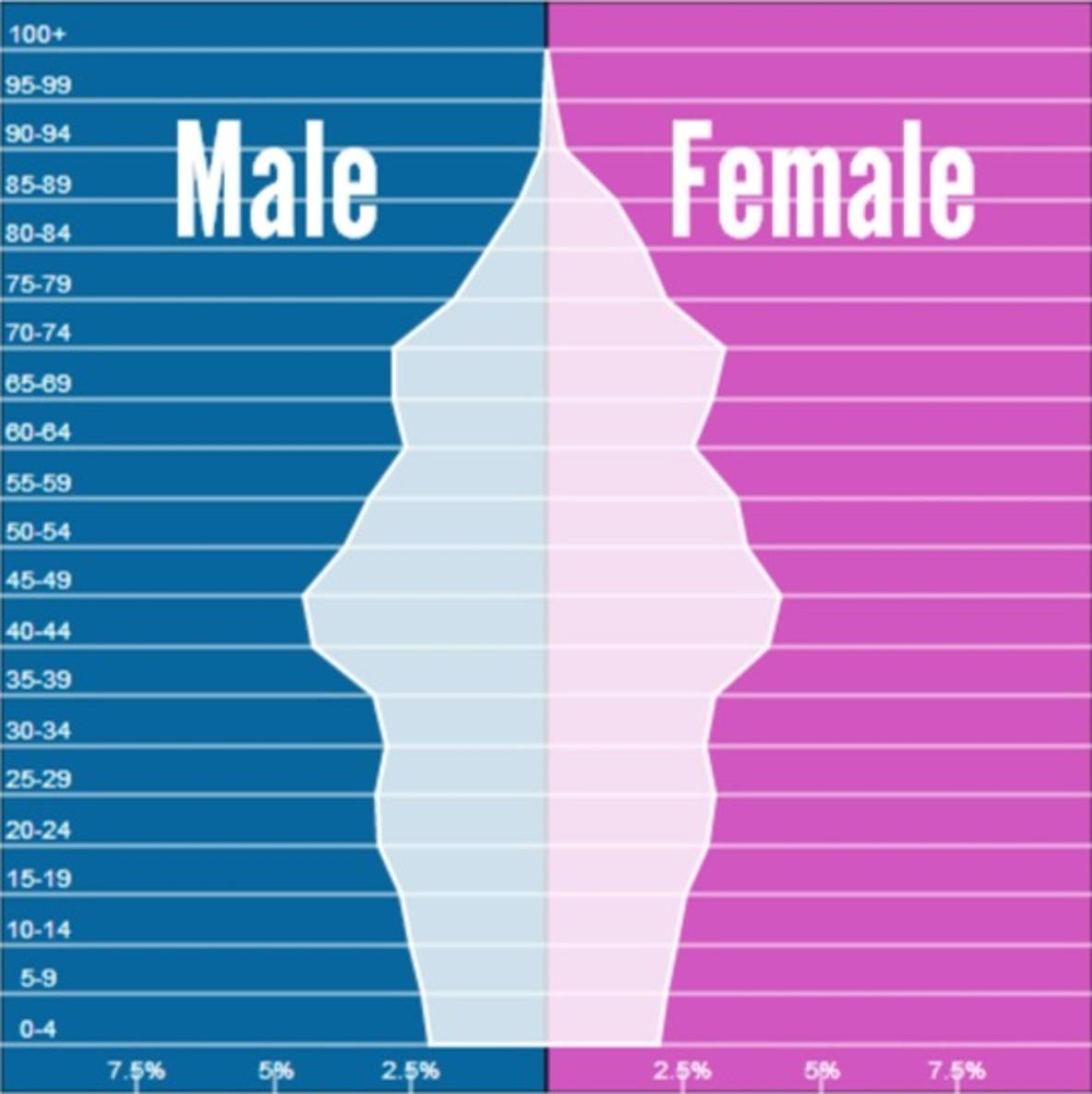

Germany’s current budget surplus is not only the result of low public spending – it is also collecting a lot of taxes. Looking at the demographic pyramid, it is possible to see that, compared to other G7 countries, with the exception of Japan, the percentage of the German population in their 40s and 50s is particularly high. While German taxpayers continue to be a reliable source of income for the country, without a massive boost in investment, especially in education, it will be increasingly difficult for the country to support the forthcoming pension burden. Summarising these issues in one sentence, the country is living on the fruits of its past labour; but it must do more if it wants to ensure its economic longevity.

(http://populationpyramid.net/germany/)

Germany is not as strong as we have been led to believe. As soon as we go deeper and beyond the macroeconomic “wunders” and look closely at the foundations of the current prosperity, the picture is more fractured; more worrying. It would be naïve to resort to the German model and to Germany itself to rescue Europe because we would be pinning our high hope on the wrong leader at a time when new solutions are needed to the Eurozone crisis.

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article. They also have no relevant affiliations. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.