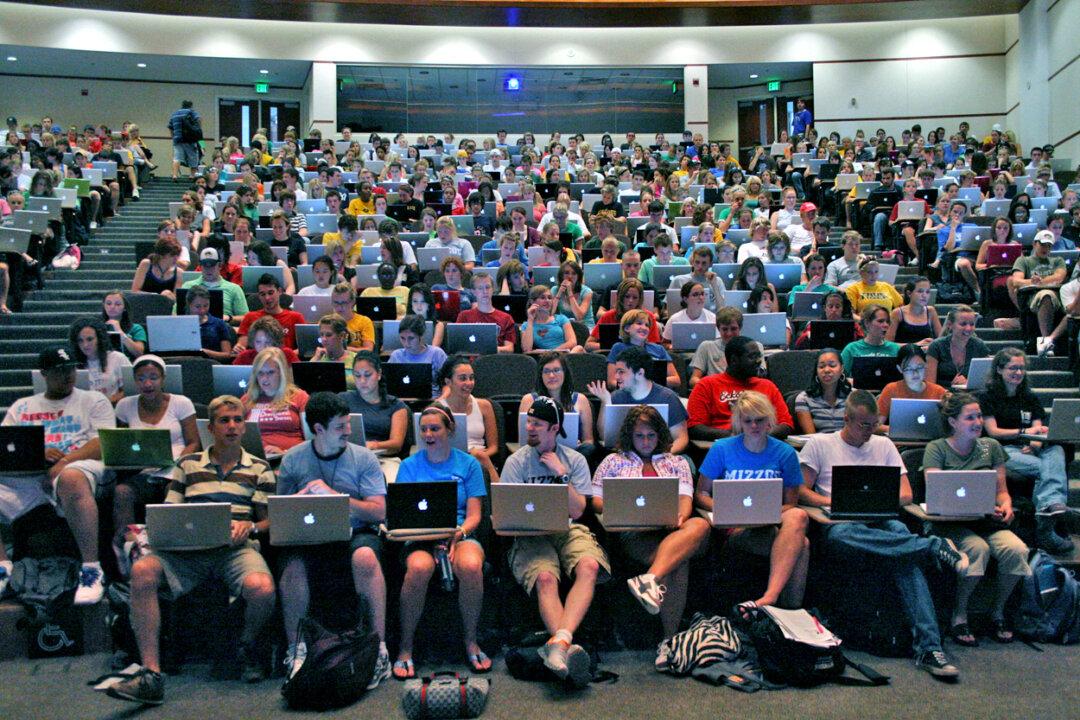

Technology is an established part of the lives of students. But university lecturers are becoming increasingly frustrated at how they must compete with tablets and laptops for students’ attention in the lecture hall. In the US, Dartmouth computer science professor Dan Rockmore has recently stoked debate in a New Yorker article arguing that laptops should be banned in the classroom.

Perhaps weary lecturers should be looking at the problem from a different angle and asking whether social networking sites such as Facebook can actually become a good place to teach. Or at least communicate with their students.

Some research has argued that Facebook and other social media networks have educational potential. Facebook can promote interaction between students and teachers – such as making announcements, discussions and sharing resources.

Other South African research investigating student use of Facebook and lecturer engagement with students via the platform found lecturers saw it as easier and quicker way to contact students. Students, particularly shy ones, were more comfortable asking questions via Facebook and they also felt lecturers were more approachable after they had interacted with them via Facebook.

But teachers have to combat the fact that growing evidence suggests the value of Facebook in higher education does not yet relate to formal learning at all, but rather to students’ quest for social networking.

Previous research has found that students prefer to keep Facebook for their personal lives rather than bringing it into the educational setting. They prefer to use Facebook for more informal learning (communication about course content and peer support) rather than formal learning.

Facebook can also be a useful tool to help students integrate into university life through meeting friends and providing a good network for support and sharing information about the course.

Research exploring Twitter in academia has also found it is a useful and viable learning tool. It can enhance active and informal learning through increased (24/7) communication and allow students to create and share ideas as well as foster collaboration outside and inside the classroom.

Stay Professional

But students and teachers need to be aware that their online activity leaves a digital footprint and they need to be professional in the way they interact online. Reports have highlighted cases of people being sacked due to unprofessional behaviour online.

My recent research has investigated the attitudes of university teachers to the use of Facebook in the classroom. I found they do not tend to use such tools in their teaching, but would like more guidelines about online professionalism and how to use Facebook for educational purposes.

Those teachers who do use Facebook in their teaching found more positives than negatives, suggesting it enhances communication between lecturer and student. Facebook was viewed as beneficial because it increased and enhanced the student experience through class discussions outside of the classroom.

But teachers are aware of the importance for both lecturer and student to be conscious of their digital footprint and adhere to professional standards online.

Using social media to teach is still a rarity. But there are many social media tools educators could utilise such as Twitter, Instagram, or Pinterest. Deborah Abdel Nabi at the University of Bolton even successfully uses Second Life to enable students to learn the psychology of cyberspace.

There is also continuing interest in how to use “off-the-shelf” computer games to teach. Some schools have employed computer games in the classroom to teach a variety of subjects in creative ways.

More should be done to encourage and support the use of social media within teaching and learning. Increasing ways to engage students and encourage students to learn outside of the classroom environment is valuable to everyone. It’s either that, or find that half the class is playing Candy Crush instead.

Julie Prescott does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

*Lead image via Brett Jordan, CC BY