In my first career as a pharmacist, I worked in more than 30 pharmacies across Nova Scotia, filling more than 100,000 prescriptions between 1990 and 1995.

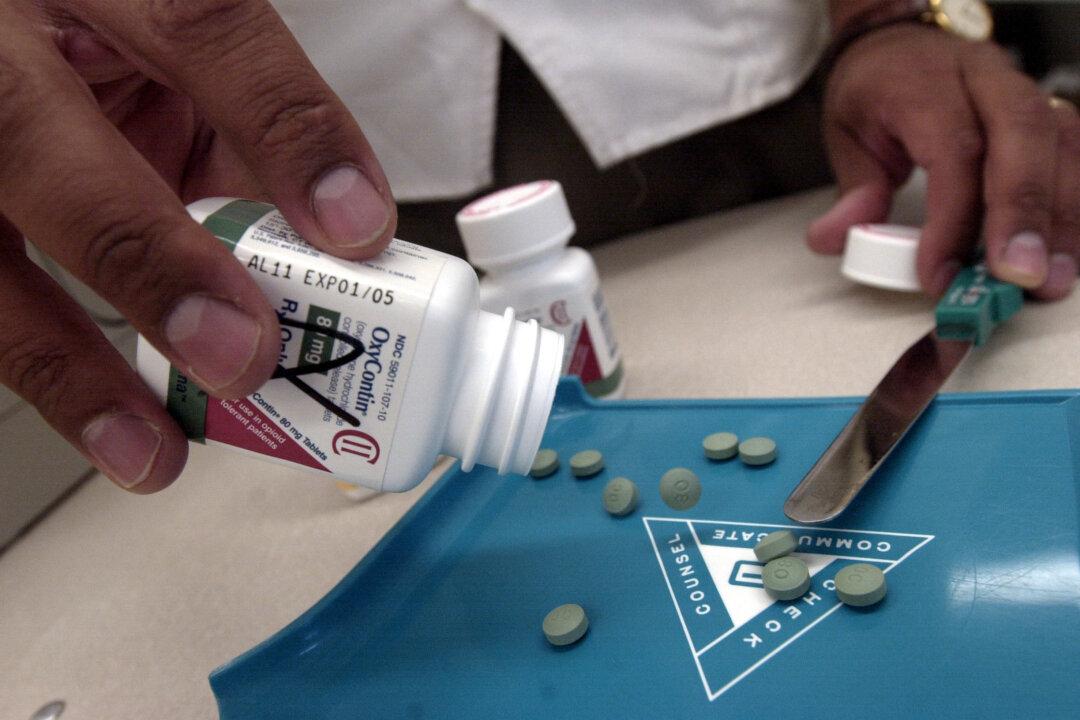

Some of these were for strong painkillers called opioids—drugs like morphine and oxycodone, which are chemically and biologically very similar to heroin. Back then, these drugs were generally reserved for patients with acute, severe pain or pain due to cancer.

Twenty years into my second career as a physician, much has changed. In Ontario, about 10 people die accidentally from prescription opioids every week, often in the prime of life. Across Canada, overdose deaths have risen and addiction rates and demand for treatment have skyrocketed.

This happened because doctors began prescribing opioids more liberally for patients with chronic pain. Sometimes this leads to meaningful improvement, but frequently it does not. By the time failure is apparent, patients are often “opioid dependent,” meaning the body has come to expect the drug and will revolt violently if it is stopped. And so opioid treatment is continued—and doses escalated—in a dangerous, often futile search for relief.

We are now in a very difficult position. On one hand, we have millions of chronic pain patients seeking help, often in the form of a prescription. On the other, we have an epidemic of addiction and death.

The false notion that opioids are safe, effective treatments for chronic pain was inculcated by the companies that manufacture them, with self-styled “experts” preaching this gospel to front-line physicians. Incredibly, this happened in the absence of good evidence that the benefits of long-term opioid use outweigh the risks.

The United States and Canada have both declared there is a prescription painkiller public health crises—in the U.S., about 17,000 people die each year from the drugs. But the countries have reacted very differently. In 2007, Purdue Pharma pleaded guilty in the United States to misleading doctors about OxyContin, a felony accompanied by a $634 million fine. No similar action occurred in Canada.

In 2011, a major White House report acknowledged prescription drug abuse as the country’s fastest growing drug problem, establishing goals and timelines for addressing it. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracks opioid deaths and prescribing nationally, and describes how some states have managed to reduce prescribing.

In contrast, there is no national system of surveillance in Canada, and even the number of Canadians who die annually from opioids is unknown.

The federal government recently handed responsibility for tackling the epidemic to the Canadian Centre for Substance Abuse, an inadequately resourced non-governmental organization funded primarily by Health Canada that also addresses the abuse of alcohol and illicit drugs.

In 2013, an advisory council to the centre produced a 10-year strategy to combat the opioid crisis, but its 58 recommendations were not prioritized (as they surely should be), and are to be implemented by volunteers from other organizations.

In February, the federal government announced funding to address prescription drug abuse as part of the low profile National Anti-Drug Strategy, a group headed by the Department of Justice and historically undermined by restrictions on information sharing. These initiatives give the regrettable impression of being ornamental rather than substantive.

We now face a public health crisis of exceptional scale—an epidemic fuelled by well-meaning doctors, expectant patients and corporate interests, and perpetuated by governmental inertia. While we await federal and provincial interventions of substance, some pragmatic solutions have already been suggested.

Doctors need better education, independent from the pharmaceutical industry, regarding pain and its treatment. We must start prescribing opioids more cautiously; otherwise, nothing will change. A national assessment of the toll exacted by opioids is long overdue. How can we fix a problem we don’t even measure?)

Every doctor and pharmacist should have real-time access to a patient’s full medication profile, as has been the case in British Columbia for almost two decades. Drug companies should be compelled to conduct large-scale evaluations of the benefits and risks of their drugs, rather than small studies aimed at getting their products to market. Patient and physician registries should be implemented for high-dose opioids, facilitating targeted interventions intended to maximize benefit and minimize harm.

Finally, we need better treatments for pain, including drugs that alleviate pain safely and effectively. This is a lofty long-term goal. Until then, we must collectively lower our expectations of what pills can do for patients with chronic pain.

Unless that message sinks in and a measure of respect for opioids resurfaces, these drugs will continue to cause immeasurable harm.

David Juurlink is an expert advisor with EvidenceNetwork.ca and Professor and Head of the Division of Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology at the University of Toronto. Article courtesy TroyMedia.com