Relying on social groups to solve problems may pre-empt the motivation for independent analytical thinking, according to a new study on the impacts of social learning in networks from a broad cultural perspective.

Social networks encompass many scenarios, from divisions within organizations, to fraternities and sororities, to connections on Facebook and Twitter.

While social learning “is a key cultural mechanism that improves the performance of individuals and groups,” write psychologist Azim Shariff and colleagues in the paper, watching and copying others while seeking solutions has some limitations on analytical development that drives innovation.

“Social networks are extremely convenient because they give you the response,” says co-author Jean-Francois Bonnefon, who studies judgment and decision-making at the National Center for Scientific Research in France.

“You have a problem, you go on YouTube and you see someone solving your problem and you imitate the solution. And that works short term. But that will not tell you how to think through the problem so that you can generalize the solution to a related problem. You become dependent to your social network.”

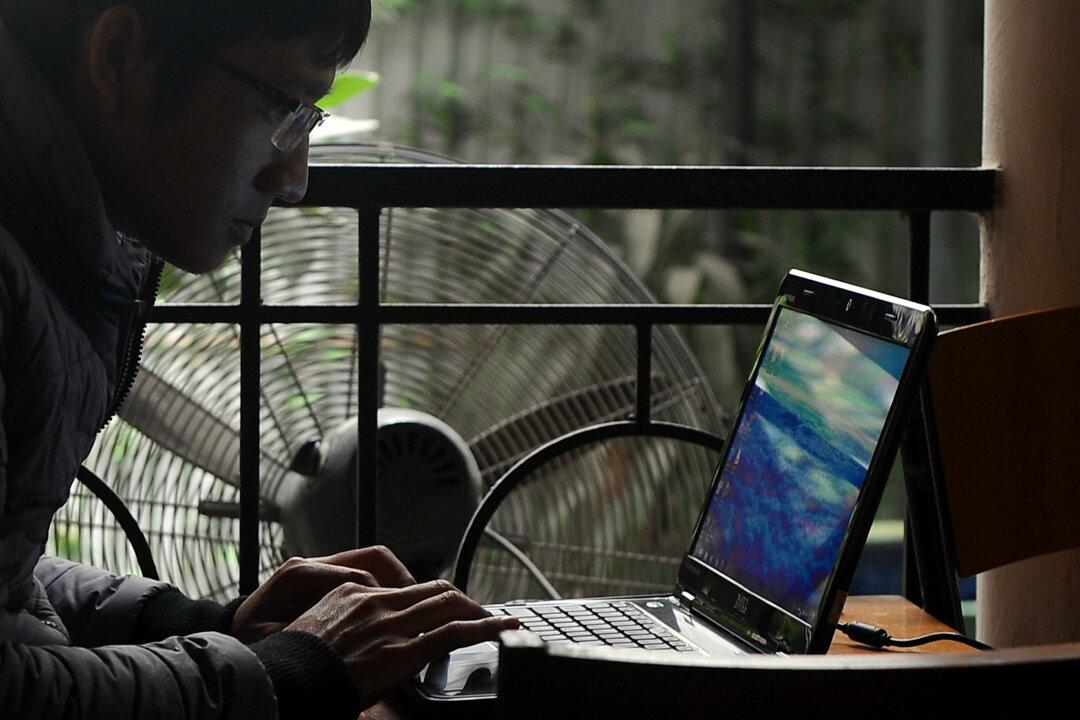

The study, conducted at the University of Oregon, involved 100 subjects, whose average age was just under 20. Working alone on a computer, each subject faced seven questions and had five opportunities to provide a solution.

A control group involved individuals working solo, while other subjects were placed randomly in groups representing four differently configured network clusters. Subjects in the experimental groups tackled each question alone under a time limit in five rounds. In each subsequent round, subjects saw the answers provided by others in their group. As the rounds progressed, each subject could stay with an answer or adopt one from others in their network. As the sequence progressed, more correct answers emerged.

“If you have a good enough system to get information, you don’t have to think at all,” says Shariff, who heads the Culture and Morality Lab of the department of psychology at the University of Oregon.

“You don’t need to develop a solution yourself. The problem with that, from a cultural evolutionary standpoint, is that if nobody is actually out there discovering solutions, if everybody is just imitating things, we create no new knowledge. We need people who are actually figuring out these questions.”

Notably, the researchers found that networking participants were able to use information from others to solve each problem. Subjects also realized along the way that analytical thinking was required, but they started from square one each subsequent problem.

“The social information is useful—it helped participants get to the answer—but it didn’t help them understand the thinking process underlying that answer,” Shariff says. “So when confronted with another similar question, it’s as if they had learned nothing about how to solve it.”

Additional researchers contributed from the Masdar Institute of Science and Technology in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, and the University of Edinburgh in the United Kingdom. The findings appear in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

Source: University of Oregon

Republished from Futurity.org under Creative Commons license 3.0.