As a professor at Texas Tech, Dr. Chuck Cannon has been, among other things, working to create a system of DNA fingerprinting for tropical trees to undercut the global illegal logging trade.

“If we just enforced existing laws and management policies, things would be pretty good, but unfortunately, that is where things fall apart in many tropical countries,” Cannon, who has spent the bulk of his long career in Southeast Asia, told mongabay.com in a recent interview.

In both the EU and the U.S., international trade laws have been passed that require the legality of imported natural resources, such as timber. Currently, there is a demand for a system to quickly and cheaply verify the legality of these resources. The idea behind DNA fingerprinting is that regulators could take DNA samples from imported wood to verify that the products are the correct species and are coming from legal localities. Though many challenges remain before such a system could be implemented, Cannon thinks it has the potential to work.

“The trends around the world can’t be ignored,” Cannon told mongabay.com, “continued forest conversion, continued illegal logging, increased domestic and global consumption, and generally weak governance. The time for a revolution in conservation science really is now. Unfortunately, a magic bullet doesn’t exist that can solve all of the problems. The most successful programs are local, with a long-term personal commitment, and require a lot of unglamorous hard work.”

Born and raised on a small cattle farm in Texas, Cannon graduated from Harvard and received a PhD in Botany from Duke University. After teaching for several years at Texas Tech, he started the Ecological Evolution group at the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Yunnan, China in 2007 as a Professor in the Chinese Academy of Sciences. He returned to teach full-time at Texas Tech in 2011.

“The idea that we can ‘preserve’ biodiversity is misguided,” Cannon says, “something that has always been changing, especially given the fact that the forests in which those organisms evolved frankly do not exist anymore, due to human conversion and ongoing climate change. We need to learn how to promote adaptation and change in biodiversity, not attempt to freeze it in time or lock it down…You hear about efforts to end extinction. That’s kind of like being in an airplane that is going down and your solution is to stop gravity. A better solution might be to find a graceful way to lose altitude and make a safe landing.”

An Interview with Dr. Chuck Cannon

Mongabay: What is your background? How long have you worked in tropical forest conservation and in what geographies? What is your area of focus?

Dr. Chuck Cannon: I grew up on a small cattle ranch in west Texas, USA. It is basically desert there and I had no idea that I would spend my career working in the Asian tropics. But while I was an undergraduate at Harvard University, I had the opportunity to spend a year at a remote research station in the Gunung Palung National Park, West Kalimantan, Indonesia. I fell completely in love with the teeming life in a tropical forest, the riotous green of it all, even if you rarely see the sun and sometimes it felt quite claustrophobic.

Mark Leighton was an anthropology professor at Harvard and he was recruiting students as research assistants who were also interested in conducting their honors thesis research. Because of my intense interest in hominid evolution, I wanted to study primate behavior as a precursor for things like bipedalism. My research project compared macaque and gibbon locomotor ecology. We also performed a lot of general observation for Dr. Leighton’s overall project, including vertebrate censuses and vegetation phenology surveys.

After getting up at five AM for several months to find my study subjects before they left their sleeping tree, I had about five minutes of data. I quickly figured out that trees, on the other hand, don’t move and you can tie a hammock between two of them during lunch time and for an afternoon nap. Although my shift to tropical botany was out of laziness really, I think the choice was a wise one. While we are all familiar with trees, we don’t actually understand their biology very well. They live on a different time scale, pursue radically different strategies, and just generally have a very different perspective on the world. I found myself completely fascinated by their very strange world.

That first trip to Indonesia was in 1987 and lasted a year, the vast majority of it spent up at the research site. In 1990, I went to Cameroon, in West Africa, where I worked for the Wildlife Conservation Society in the Korup National Park. My job was to conduct a biological survey but we ran into a lot of difficulties, logistic, health-wise, and political, and didn’t make much progress. In 1991, I went back to West Kalimantan, Indonesia to study selectively logged forests on a grant from Conservation, Food, and Health.

The results of that study were published in Science magazine in 1998. I felt we were reporting great news: selectively logging actually leaves behind a forest with a lot of diversity and high conservation value! But I mainly caught flak for it. It went against the dogma that ’selective logging‘ equals ’deforestation'. Colleagues accused me of encouraging logging but I didn’t agree. Humans all around the world have readily converted their available natural resources into wealth. It’s naive to expect people and governments in tropical countries to forsake the same path of development all of the temperate countries had followed. I’m glad to see now that many conservation biologists acknowledge that the future of tropical forests lies in altered and degraded forests and that they have considerable resilience. If we just enforced existing laws and management policies, things would be pretty good, but unfortunately, that is where things fall apart in many tropical countries.

| |

For my PhD research at Duke University, I studied the phylogenetic biology of tropical stone oaks (Lithocarpus, Fagaceae). In 1997, I received a Boren Fellowship and spent a year and a half as a Research Fellow of the Institute for Biodiversity and Environmental Conservation at the University of Sarawak, Malaysia. That was a great fellowship as I travelled all over the northern part of Borneo and spent a considerable amount of time in the Kinabalu State Park, Sabah. That project led me to think a lot of about the biogeography of the region. I continued this work for another year as a post-doc at Duke University with Dr. Paul Manos and then I was able to expand the collecting to peninsular Malaysia.

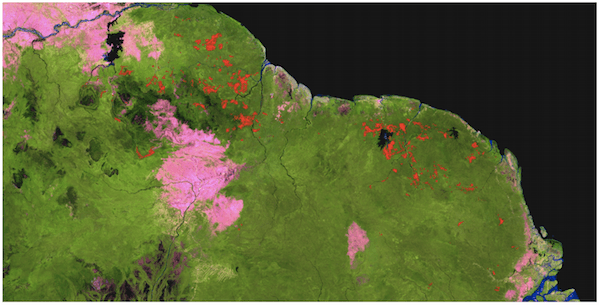

I have also spent a considerable amount of time on Sulawesi, Indonesia, working with the Indonesian program of the Nature Conservancy. I think Sulawesi is one of the most fascinating places on Earth. I first worked in the Lore Lindu National Park, to help create an accurate vegetation map but then went on to assist with an Ecoregional Conservation Assessment of the entire island. For the ECA, I travelled across the entire island and visit many different forests and protected areas. I came to really appreciate the wide diversity of forests, soils, climates that exist on that one weirdly shaped island. I was just back in north Sulawesi in July 2014, teaching on a field course organized by Myron Shekelle of Ehwa Woman’s College in Korea.

From 2007 until 2011, I was a full-time Professor in the Chinese Academy of Sciences, based in the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Yunnan, China. Before 2006, I wasn’t even aware there was tropical forest in China but I met the director of XTBG, Dr. CHEN Jin, at the ATBC meeting in Kunming that year. I was really impressed by Jin’s sincerity and deep passion for research and conservation and the obvious importance of China to the future of Southeast Asia made the opportunity of working there very intriguing. I established a new research group focused on “Ecological Evolution”. Although it’s unusual, I’ve started to prefer the term to the more common “Evolutionary Ecology.” The idea that ecologies evolve is a good one. It was a fantastic 4.5 years and I have continued to remain active at XTBG, primarily in participating in field courses and advising students. Actually, the PI position of the Ecological Evolution group is open right now so if any young tropical biologist is looking for a great challenge, one is available.

My work is broadly focused on conserving and managing Southeast Asian forests. The trends around the world can’t be ignored: continued forest conversion, continued illegal logging, increased domestic and global consumption, and generally weak governance. The time for a revolution in conservation science really is now. Unfortunately, a magic bullet doesn’t exist that can solve all of the problems. The most successful programs are local, with a long-term personal commitment, and require a lot of unglamorous hard work.

Mongabay: Are you personally involved in any projects or research that you feel represents emerging innovation in tropical forest conservation?

Dr. Chuck Cannon: I’ve been examining and promoting ideas and technologies to create a DNA fingerprinting approach to prove the legality of tropical timber harvest. International trade laws were passed both in the EU and U.S. that require legality of imported natural resources, so a real demand exists for a robust and verifiable system but there are a huge number of challenges. A Singapore company, Double Helix Tracking, and Biodiversity International, a division of CGIAR, are actively pursuing these efforts. We’ve gone through a lot of debate about the best approach and I’ve wanted them to embrace next-gen DNA sequencing technologies. The huge amounts of data and new analytical approaches are unfortunately quite daunting with next-gen sequencing, so it’s been slow going. I think it has the potential to work in the end but how exactly it will be applied, and by who, remains a mystery.

While this is definitely just emerging, I have been promoting the idea of using “citizen science” approaches in tropical conservation. We clearly do not have enough ‘experts’ working in these countries to collect and process the data necessary to properly monitor and manage these forests. The change is so rapidly, the areas so vast, and as you move across Asia, the level of variety and endemism is staggering. We’ve held one field course and have another planned for July 2015 for U.S., Chinese, and SE Asian graduate students to come together and work on citizen science projects and how to leverage that power into their own research.

In connection to citizen science approaches, I’ve also been promoting the concept of ‘near-sensing.’ It is more of a concept than a protocol. What I mean by ‘near-sensing’ is the use of advanced digital technologies by individuals to monitor and document forest condition, structure, and composition. ‘Remote-sensing’ fundamentally changed our ability to monitor both historical and on-going forest change at the landscape scale. Now, with a large fraction of the world’s population possessing powerful digital technology right in their pocket, in the form of a smart phone or intelligent point and shoot camera, GPS technologies, combined with the ability to immediately share images and data with the world, I think everyone can and should participate in basic environmental monitoring. I’m very excited to see how the Global Forest Watch, initiated recently by World Resources Institute, develops.

Mongabay: Can you give an example of how the DNA fingerprinting approach would work in action?

Dr. Chuck Cannon: Ideally, a customs agent could obtain a sampling of wood from a shipment of timber during the process of importation. DNA could be extracted from the wood and the DNA sequence could be tested against a database to determine two aspects of legality :

1) whether the wood is the ‘correct’ or ’reported' species or whether it comes from a protected species;

2) whether it was harvested from the ‘right’ place or whether it was poached illegally from a protected area.

As I mentioned, both the U.S. and the EU have recently implemented laws requiring the legality of imported natural resources. Currently, determining legality depends on documents related to the ‘chain of command’ of these items. As they are exchanged, official paper documents are supposed to record their information and movement. These documents can be faked and switched etc. You would rather have some marker that was intrinsic to the wood. In other words, if you have a piece of wood, you can extract the necessary information directly from it. That’s why we are interested in DNA. It is in every cell of a plant, even in the wood.

We know that we can extract DNA from wood, even ancient wood and some processed woods. ‘Wood’ is dead vascular tissue. ‘Xylem’ if you remember your basic plant biology. The genetic material is basically ‘preserved’ inside the highly lignified cell walls of this tissue as it forms. With modern DNA sequencing technologies, highly degraded DNA is no longer a problem either. In fact, you typically degrade the DNA in the library preparation.

So, we can extract the information from the tissue but there is a lot to be done still. One thing to remember about these techniques is that the data has to stand up in a court of law. Standards of legality typically go much further than publication in a scientific journal. You can’t be 80 percent confident or even 95 percent confident. Unlikely things happen all of the time in life. The results from DNA fingerprinting techniques have to be quite robust.

One way is to actually collect the DNA from the trees beforehand. You create a database specifically for those trees. They are harvested and then at the border, the customs agent can test the samples against the specially created database and know exactly whether these logs came from those trees. This has been done with some effectiveness. Unfortunately, this approach can rarely stop illegal logging, unless you are going to obtain DNA from every tree in protected areas.

The much more difficult way to use the DNA fingerprinting approach is to take any piece of wood, from any ship in the harbor, and determine what species it is and where it came from. This requires a massive database, which simply does not exist and for which there seems to be little financial support. It'd actually not be too difficult to create limited versions of this database, for targeted species, and would represent a pretty small fraction of the global trade. I think if we had a few good working examples, it would determine illegal logging— unless the market becomes domestic. In other words, if illegally logged timber is used locally, it would never be tested.

I think we’ve long passed the point of ‘Peak Timber,’ where tropical timbers are easily harvested from big tracts of ‘old-growth’ forest so the market should transition toward more and more plantation timber. This would make the whole process a lot easier too, because wild tree species will be more difficult to identify than plantation species. Actually, I am not sure about the global market these days, what fraction of the trade still comes from ‘old-growth’ forest. If anyone knows, please tell me!

Anyway, you might think, wow, DNA fingerprinting sounds like a great idea and then lots and lots of questions pop up. I'll address some of those in the following section.

Mongabay: What are the obstacles to implementing this approach?

Dr. Chuck Cannon: As I said, the whole idea rests upon the creation of an adequate database of DNA markers.

In the first case above, where you’ve collected DNA from the harvested trees and created a database specifically for these logs, it’s relatively easy and straightforward. This is a viable option for ‘good guys’ who follow sustainable practices and want to distinguish themselves from the ’bad guys’ who are illegally harvesting and trading timber. The ‘good guys’ have to receive a reward though or they will not maintain these practices. A market premium is necessary. People have to be willing to pay more for timber that they know beyond the shadow of a doubt is legal and sustainable. While the premium timber market is developing, it remains a fairly small portion of the overall global market, a lot of which is not well monitored or regulated.

Therefore, one major obstacle that exists is limited reward in a quickly saturated market for the loggers who go the extra mile and produce legal timber.

Also, determining the identity of the wood using DNA markers can be trickier than you might think. While the species bar-code has its purposes, I don’t think it would be effective for most tropical timber species and I seriously doubt it would stand up to a serious legal challenge. The species bar-code concept has been discussed a great deal and many people want to believe a simple answer exists for species identification. Unfortunately, evolution is messy and one little fragment of DNA is not going clarify much.

Finally, determining the geographic origin of a piece of wood will require an extensive database, with DNA markers not just for species but for geographic locations. This all depends on the biogeography and biology of a tree species, so for some it might be relatively easy while for others it would be impossible. For example, I don’t think you could ever develop such a system for figs. Both their seed and pollen disperse extremely well and over long distances. All of this migration of genetic material quickly washes out any spatial patterns. Even with perfect data, you would still be challenged to do this for figs.

Good candidates include things like dipterocarps of Southeast Asia, because they produce relatively massive seeds that do not disperse far and germinate immediately into a seedling, so strong geographic patterns should persist in their DNA.

It also depends on the spatial accuracy you require. It would probably not be difficult to distinguish between logs harvested on different islands in Southeast Asia but if you wanted to know whether a tree came from a protected national park or the logging concession across the river, that would be impossible. You’re best off going back to the first method.

We know surprisingly little about the genetics of most tropical tree species, so creating this database would require a rather huge and unprecedented effort. I do still believe that it could be done successfully for a large number of currently traded species. It just requires the initial investment in the creation of the database. There is a currently a large effort, led mainly by Bernd Degen at the Johann Heinrich von Thünen Institute in Hamburg, Germany, who is currently leading a multi-EU/multi-African survey of tropical timbers in Western Africa to test the idea on a large scale. These efforts are still experimental and being developed now.

Mongabay: What’s the next big thing in forest conservation? What approaches or ideas are emerging or have recently emerged? What will be the catalyst for the next big breakthrough?

Dr. Chuck Cannon: It may sound a bit cliche but to me, the major game changer in the past couple of decades has undoubtedly been the internet. Its impact is hard to estimate. We now have this global platform for sharing and finding information that did not exist twenty years ago. And it completely dominates the lives of the majority of the global human population. Its impact and scope continues to rapidly expand. Conservation biologists have actually made pretty good use of it, as a way to spread awareness, as a tool for activism. There are many examples of its impact on forest management throughout the tropics. I’ve now led a couple of online discussion courses, where U.S., Chinese, and Asian students meet on various social media platforms to discuss lectures and readings. Besides the intellectual exchange, the students learn a lot of skills about interacting globally with their peers. It really does require a different set of social skills to communicate effectively in group online meetings, with members spread across the globe. I don’t think that I do it very well and I still feel uncomfortable when I see my talking head bobbing around on the computer screen.

I think another major impending breakthrough is our basic understanding of biodiversity. We have tended to take a rather uncritical view of ’species’ and have always assumed that more is better. I can’t tell you how many times grant proposals, scientific publications, etc start off with the words — “The place I work is the most diverse in the world...” as if its conservation and biological value is intrinsically tied its the species richness, which is rubbish. Similar to discussions among economists about why GDP is not an accurate assessment of a country’s wealth, I think species richness is not a terribly accurate or meaningful indicator in terms of natural wealth or conservation value. First of all, we have no adequate theory of how species arise in the tropics or what that richness really means for a forest. These questions are very important because species are the currency of conservation but how do we convert and manage this ‘value’ among the different groups of organisms. I do feel we should abandon the ‘gold standard’ of the ‘biological’ species concept, which desperately needs to be renamed. Other species concepts are just as ‘biological’. Ernst Mayr was very clever. By giving his concept that name, he implied that all other concepts are non-biological. As more and more evidence and good data becomes available, we’re learning that species are quite flexible and fuzzy entities and have always changed through time. The idea that we can ‘preserve’ biodiversity is misguided, something that has always been changing, especially given the fact that the forests in which those organisms evolved frankly do not exist anymore, due to human conversion and ongoing climate change. We need to learn how to promote adaptation and change in biodiversity, not attempt to freeze it in time or lock it down.

You hear about efforts to end extinction. That’s kind of like being in an airplane that is going down and your solution is to stop gravity. A better solution might be to find a graceful way to lose altitude and make a safe landing. Mongabay: What do you see as the biggest development or developments over the past decade in tropical forest conservation?

Dr. Chuck Cannon: The continued shift in global awareness and collaboration has been rather remarkable. There was a real sense before that people who cut down or modified forests were evil or stupid in some way. We had to ’stop‘ them, when, in fact, they were just doing what people in temperate regions have been doing for centuries. The sense was that the problem was ’over there', with enforcement, with awareness, instead of recognizing that it is the level of consumption and demand for resources in the temperate countries that was driving the change. This goes all the way back to the spice trade. The change in tropical countries is largely driven by external forces and desires created by consumer capitalism. Local food movements, real efforts to be a smart consumer, allowing the supermarket produce aisle to change with the seasons, I think these things all reflect a shift in focus. Change starts at home and the rich nations are the ones really creating the demand that has led to a lot of the unwise use of tropical forests.

This also connects to ideas that we do really need new economic models, ways of accounting for ecosystem services and natural capital. These things had no value BEFORE they were converted, were not considered part of the economic equation. I really hope that these new economic models can grow and gain in influence. The idea of continually maximizing economic grow rates is obviously absurd. Where does it lead? Again, going back to the fundamental forces of nature, there are limits to growth. Our societies are based on a few limited resources. How we deal with these valuable and hotly contested commodities will determine our future.

Mongabay: What isn’t working in conservation but is still receiving unwarranted levels of support?

Dr. Chuck Cannon: In the past, we put too much focus on ‘wilderness’ and ’pristine forest‘. ’Wilderness’ is already extinct. There is now no corner of the globe that humans have not modified or where our influence does not reach. We are responsible for managing the world’s forests. Often times, by focusing on undisturbed forest, we put our effort into protecting areas that are actually least threatened. If it is still pristine, there is generally something about it that is protecting it naturally because if it were easily convertible into wealth, it would have happened. These areas are often in the mountains, not productive for agriculture, on poor soils but we focus on these areas because of their pristine condition.

Therefore, we often neglect places of great conservation value that have been recently degraded and are heavily contested but eventually represent the future of tropical forests. We miss opportunities to recapture disturbed forests and lands for reforestation and improved management, particularly in lowland areas, where both productivity and biodiversity are often greatest. Certainly, I understand the romantic notion of the deep primeval woods. I feel very fortunate having been able to spend a good deal of my early career there. But these areas are now tragically a small subset of the global forest. The majority of forests have been degraded or converted but they have great resilience. Of course, you will not get the same forest back but forests operate on a substantially different time frame than human economies and cultures, so of course, there is going to be a certain amount of conflict.

Wishful thinking needs to end and we need to face the hard reality of the future of tropical forests.

I have never understood the logic of biofuels. Investing so much energy, resources, and management into an energy source that produces only a slim margin of benefit is a bit like sprinting to stay in one place. It feels like a major miscalculation. I think we should instead look at our energy use and decide whether it is truly a benefit. Identify those things that are clearly wasteful and inefficient and cut them out. I think we could greatly increase the efficiency of our energy use just by preventing negligent use.

Also, by creating biofuels that grow on marginal areas, we are creating a new conflict for even those marginal lands that used to be considered unproductive and were protected simply because no one could profitably use them. But the truth is that these biofuel plants, like any other crop, are more productive and profitable on more the productive sites, like lowland alluvial soils, and so you are also creating competition with food-production. The world does exist in a certain delicate food balance and by introducing a new competitor for arable sites, could throw that balance out of whack.

This article was originally written and published by Liz Kimborough, a contributing writer for news.mongabay.com. For the original article and more information, please click HERE.