NEW YORK—Visitors from around the world are drawn to New York City’s High Line, an elevated park built on defunct railroad tracks transformed into an urban sanctuary of flowers, grasses, and trees.

Private planners inspired by the High Line’s success are now looking deep under Manhattan at a proposal to create the Lowline, billed as the world’s first underground park.

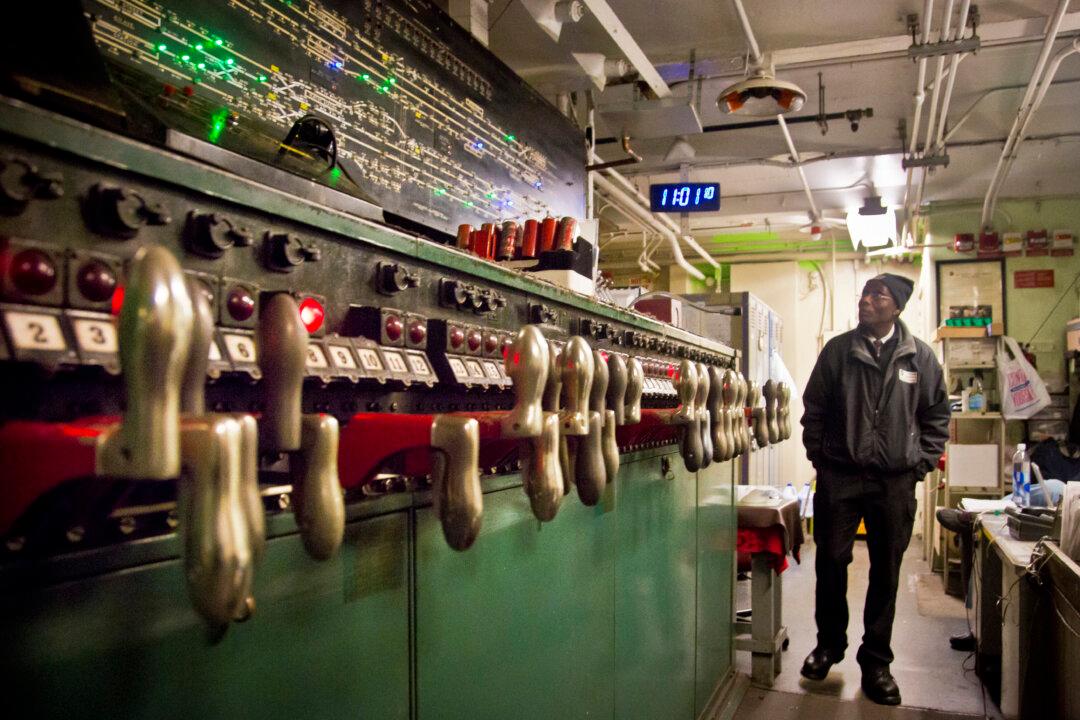

The project would occupy a 116-year-old abandoned trolley terminal below the Lower East Side that’s been used for storage since 1948.

Street-level solar collectors would be used to filter the sun about 20 feet down to bedrock, turning the dank, subterranean space into a luminous, plant-filled oasis. The park would offer city residents a place of refuge and host art exhibits, music performances, readings, and children’s activities.

The Lowline is only one part of a Lower East Side revitalization project.

The neighborhood has an important place in the history of immigration. At the turn of the last century, newly arriving Italian, Irish, and German families made their first homes in America in its tenements. So many Jewish families settled in the neighborhood that it has been called “the American-Jewish Plymouth Rock.”

“Many people once fought to move out of the Lower East Side, and now, their grandkids are fighting to get in,” says Mark Miller, an art gallery owner whose family ran businesses there since the late 19th century. “It’s come full circle; it’s hip, happening, and historic.”

The planners—New York residents who’ve worked or lived in the area—say they’re not erasing the legacy of Orchard, Delancey, and Rivington streets, once home to the likes of Irving Berlin, George Burns, Jimmy Cagney, Zero Mostel, and Lucky Luciano.

“We’re simply taking over a space no one was using in a densely populated neighborhood that lacks sufficient public space,” says Dan Barasch, who specializes in promoting socially innovative applications of technology.

He co-founded the nonprofit Lowline project with designer James Ramsey, a former NASA engineer. The park is expected to cost about $60 million in mostly private funds, plus some government money. More than $1 million has been raised for research and design.

Ramsey and Barasch got the idea for the project when they heard about the site that was once a trolley turnaround for the line that ran across the Williamsburg Bridge to Brooklyn.

“We'd already been playing with new solar technology,” Barasch said, noting that Ramsey’s RAAD design studio firm worked on the solar concept for the terminal. “And we fell more and more in love with the idea of this public space, so we put those two concepts together.”

Transformation

Barasch estimates it will take about five years before construction begins to transform the 1-acre leftover from the past into a destination of the future.

First, he says the Lowline team of three, plus hundreds of volunteers, must tackle some technical challenges: exactly how to channel the natural sunlight from the collectors to the park below, using the latest optics. Then the best way must be found to position the sunlight so it allows plants to grow.

Several high-tech companies already have used such systems to funnel natural illumination to previously light-inaccessible areas.

“But you can’t just cut the street open,” says Barasch.

Community members had their own questions at a Lowline presentation held recently at the Tenement Museum, which celebrates the rich history of the Lower East Side. Some asked where the street-level entrances would be, how the space would be ventilated, and what kinds of plants would be brought in.

The pioneer model for the Lowline is the High Line park on Manhattan’s West Side. The 22-block aerial walkway on an abandoned freight route has galvanized a neighborhood where luxury condos, galleries, and boutiques have all but pushed out the industrial grime of warehouses and manufacturing plants.

The High Line has inspired proposals for other such New York parks, including one set on unused Long Island Rail Road tracks in Queens and another on an abandoned portion of Amtrak rails in Harlem.

The Lowline developers are also collaborating with the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), the state agency that leases the former terminal from the city. Both the MTA and city officials must formally approve what the Lowline creators envision as a not-for-profit partnership.

Not everyone is thrilled with the idea.

Kerri Culhane, associate director of Two Bridges Neighborhood Council, calls the project a “Trojan Horse” that will draw real estate investors while alienating longtime residents.

“In effect, the Lowline is a murkier, subterranean version of a corporate atrium,” she says, noting that public use will be curtailed when it’s rented as a private “event” space—one of the possible uses.

Barasch counters that the revenue would allow the park to be self-sustained, minimizing reliance on limited government funds.

From The Associated Press