WASHINGTON—The struggling and fragile democracies of Burma, Thailand, Cambodia, and electoral reform in Hong Kong are at critical junctures. The decisions that are made at this crucial time will largely determine the democratic reform of these countries in the months or years ahead, according to the testimony given at a hearing of the House Foreign Affairs Committee’s Subcommittee on Asia and the Pacific, June 11.

Promoting democracy, human rights and good governance has long been a central component of U.S. foreign policy, and its importance should not be forgotten as the United States pursues its military and economic interests, said Chairman Matt Salmon (R-Ariz.).

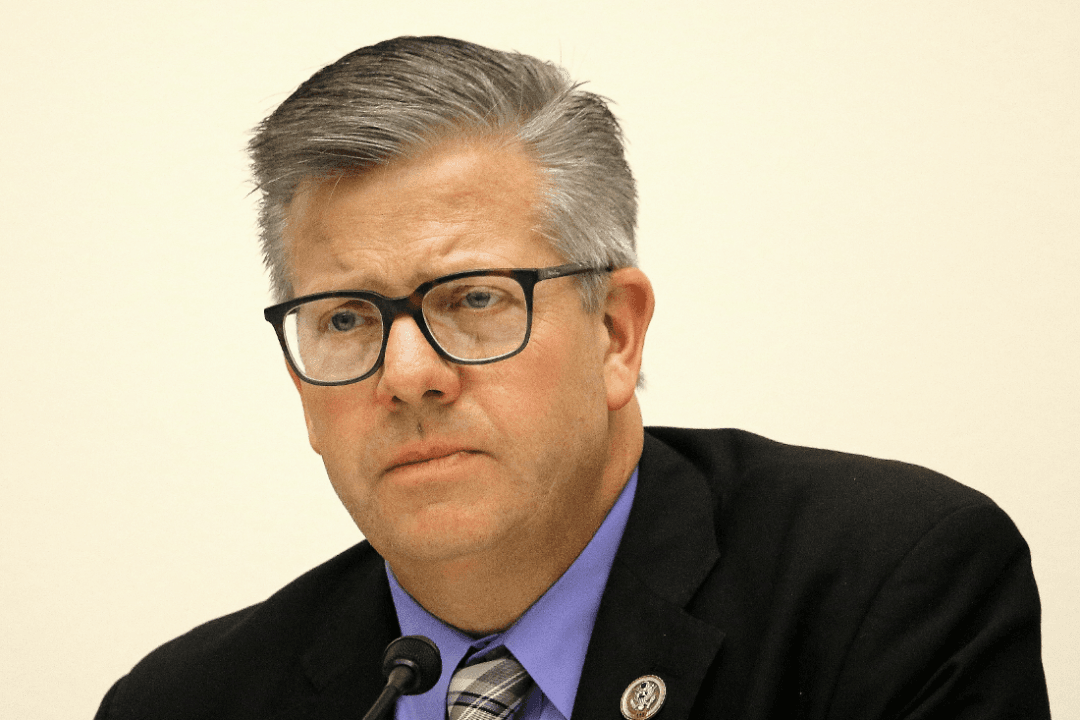

Officials from the U.S. Department of State at a June 11 hearing on democracy in Asia, before the Subcommittee on Asia and the Pacific. Assistant Secretary Tom Malinowski (L), Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor; Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary Scot Marciel (C), Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs; and Assistant Administrator Jonathan Stivers (R), Bureau of Asia, USAID. Gary Feuerberg/ Epoch Times