Football is a contact sport; it is physical, it is rough, and more often than not, it is painful. Players are virtually guaranteed to be injured at some point. But for how long do these injuries actually last, and how serious are they?

Looking deeper into Dave Duerson’s Feb. 17 suicide sheds more light on this issue.

As the New York Times reports, Duerson’s final note to his family concluded with the appeal, “Please, see that my brain is given to the N.F.L.’s brain bank.”

With this request, Duerson shot himself in the chest, preserving his brain. This past Monday, Boston University’s Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy’s researchers examined his brain. They announced that his brain developed a trauma-induced disease, chronic traumatic encephalopathy—one found in more than 20 deceased players.

As the New York Times explains, C.T.E. was a disease previously connected to boxers, and is a degenerative and incurable disease associated with memory loss, depression, and dementia. As of right now, the condition can only be detected after death.

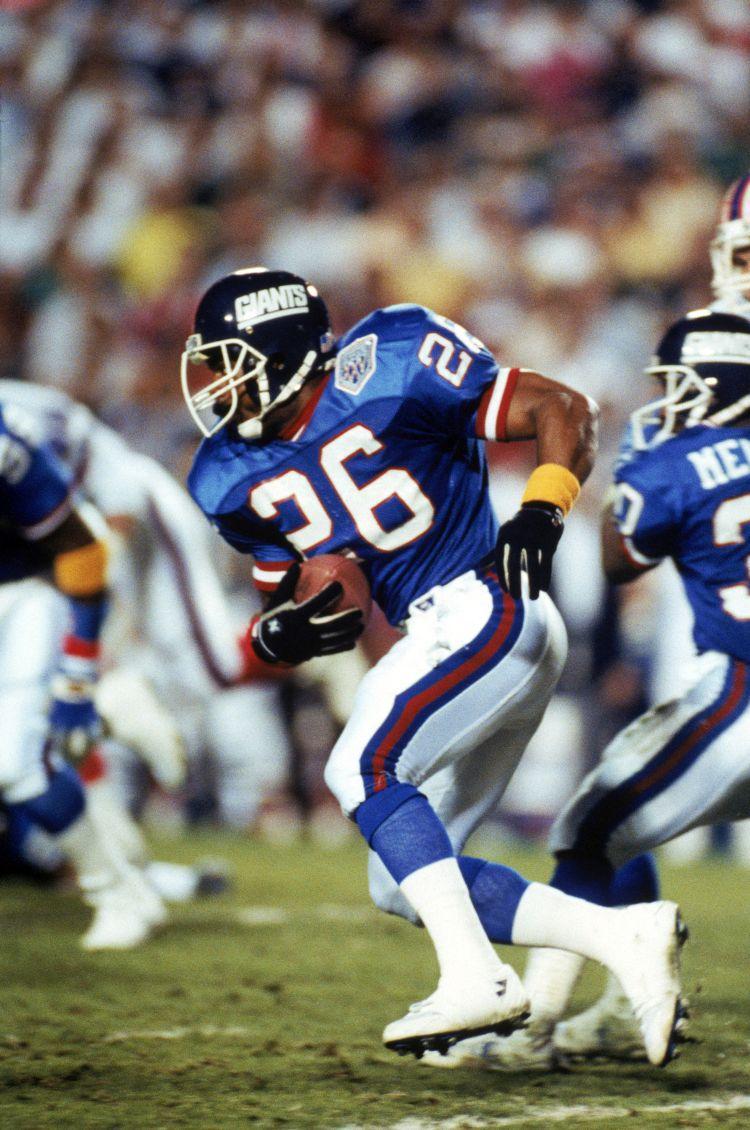

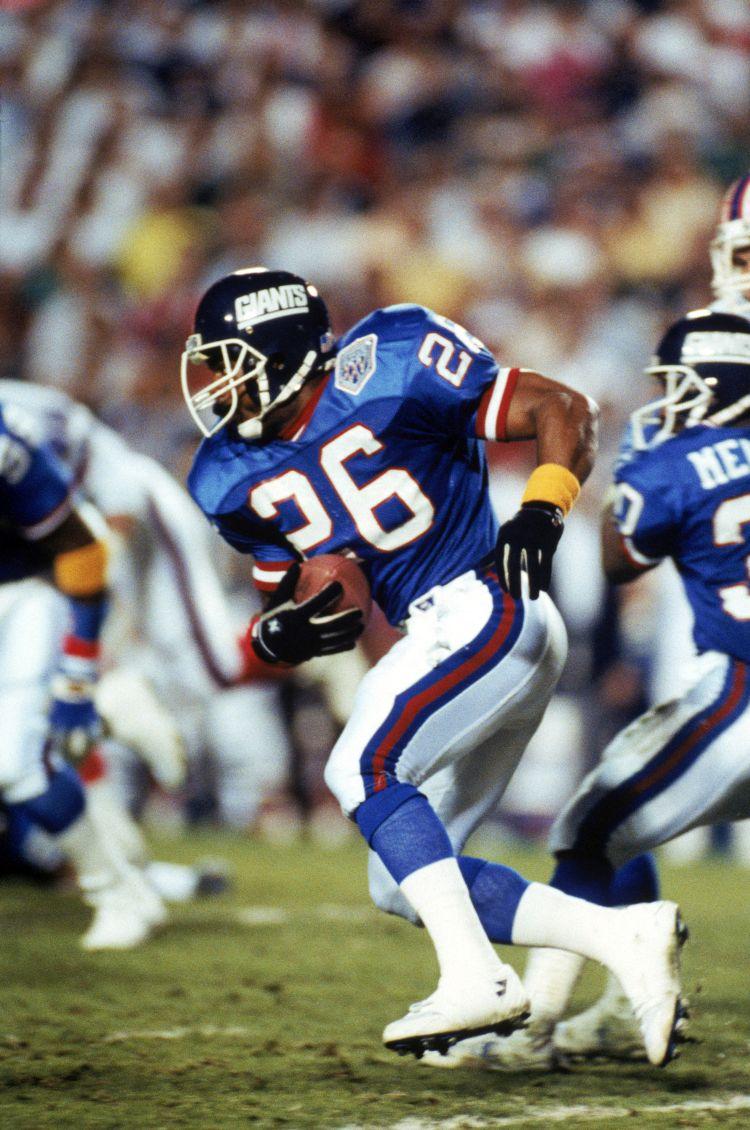

Duerson played for the Chicago Bears, New York Giants, and Phoenix Cardinals over a span of 11 seasons, during which he won a Super Bowl with the Bears in 1986, and another with the Giants in 1991. His suicide and his post-mortem diagnosed brain disease raise serious concerns about concussions and brain injuries in the NFL today.

CBS Sports also contributed to this discussion, particularly in regards to the implications in the NFL. They refer to Chris Nowinski, who is one of the directors of the BU group that researches sports-related brain injuries. CBS Sports states that the most impactful aspect of Nowinski’s study is that, yes, a singular concussion is bad, but the aggregate effect of all hits over a football-lifetime can be equally if not more problematic.

This means a lot in terms of the players’ safety in general, and how will the league address these questions, with Duerson’s suicide now looming in the fore?

Looking deeper into Dave Duerson’s Feb. 17 suicide sheds more light on this issue.

As the New York Times reports, Duerson’s final note to his family concluded with the appeal, “Please, see that my brain is given to the N.F.L.’s brain bank.”

With this request, Duerson shot himself in the chest, preserving his brain. This past Monday, Boston University’s Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy’s researchers examined his brain. They announced that his brain developed a trauma-induced disease, chronic traumatic encephalopathy—one found in more than 20 deceased players.

As the New York Times explains, C.T.E. was a disease previously connected to boxers, and is a degenerative and incurable disease associated with memory loss, depression, and dementia. As of right now, the condition can only be detected after death.

Duerson played for the Chicago Bears, New York Giants, and Phoenix Cardinals over a span of 11 seasons, during which he won a Super Bowl with the Bears in 1986, and another with the Giants in 1991. His suicide and his post-mortem diagnosed brain disease raise serious concerns about concussions and brain injuries in the NFL today.

CBS Sports also contributed to this discussion, particularly in regards to the implications in the NFL. They refer to Chris Nowinski, who is one of the directors of the BU group that researches sports-related brain injuries. CBS Sports states that the most impactful aspect of Nowinski’s study is that, yes, a singular concussion is bad, but the aggregate effect of all hits over a football-lifetime can be equally if not more problematic.

This means a lot in terms of the players’ safety in general, and how will the league address these questions, with Duerson’s suicide now looming in the fore?