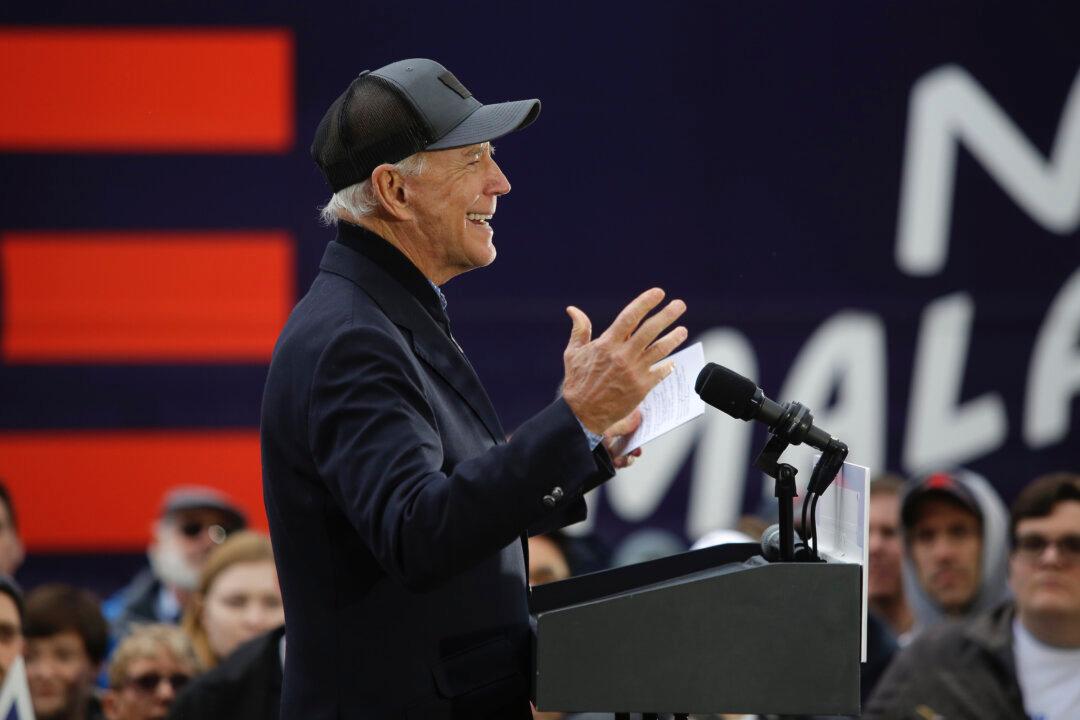

Democratic presidential frontrunner Joe Biden recently hinted at possibly selecting former Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacy Abrams as his vice presidential running mate if he wins the party’s nomination.

But Abrams, who blames voter suppression for her 2018 loss, is facing a state ethics complaint about alleged “unlawful coordination” with outside dark money groups, which are nonprofit groups that aren’t required to publicly disclose donors.