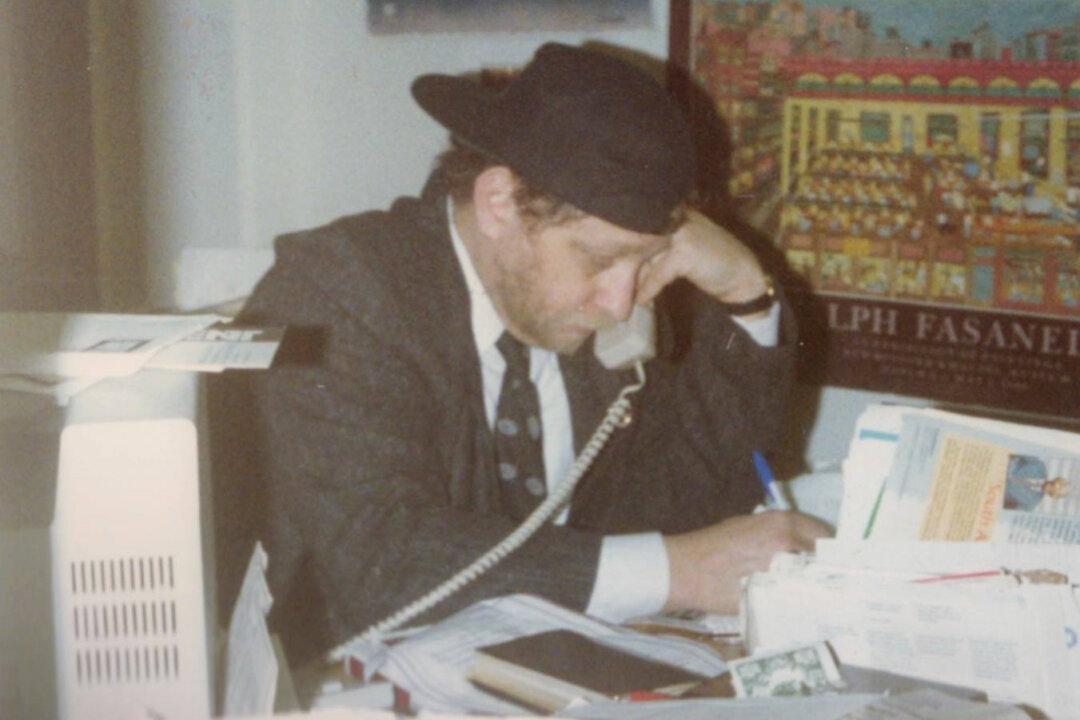

Danny Schechter, a writer, journalist, documentary filmmaker, and, above all, piercing analyst of the press, which earned him the rhyming sobriquet “The News Dissector” that often followed his name, died of pancreatic cancer in New York City on March 19. He was 72.

Schechter, born in the Bronx in 1942, was a lifelong advocate for civil rights and progressive politics. He graduated from Cornell University in 1964, later gaining a master’s from the London School of Economics; he briefly taught at Harvard University in 1969 and was a Nieman fellow in Journalism at the university in 1978.

He earned the nickname “news dissector” during his time as director of the radio station WBCN-FM in Boston from 1970 to 1977—the daily news show he ran began with the catchphrase “This is Danny Schechter, your news dissector.”

Schechter won two Emmy Awards and was nominated for two others, according to the biography on his Facebook page. He was a producer for ABC’s “20/20,” and later served as a producer for CNN.

In the 1990s he helped to found Globalvision New Media, a company that oversaw other properties, like Mediachannel.org, founded in 2000, for which he wrote a regular column picking apart what he saw as the unfounded assumptions or hidden agendas in the mainstream media. He also made half a dozen nonfiction films about Nelson Mandela, and was an outspoken opponent of apartheid South Africa. He also wrote over 12 books.

Schechter spent several years, from mid-1999 to 2001, on a topic different yet again: the persecution, by the Chinese Communist Party, of the traditional spiritual discipline Falun Gong.

His connection to that topic was Gail Rachlin, a publicist at the time and then herself a practitioner of Falun Gong. She had known Schechter for six or seven years by the time the persecution started, and had publicized many of his books. Rachlin is a spokeswoman for and was a founder of the Falun Dafa Information Center, which represents Falun Gong.

Falun Gong, which includes five meditative exercises, and the teaching of truthfulness, compassion, and forbearance, had been taught and freely practiced in China, where it was founded, throughout the 1990s. On July 20, 1999, a nationwide and ferocious campaign of persecution and propaganda against it began, leaving practitioners of the discipline inside and outside the country bewildered at how to respond.

“He called me and said, ‘How can I help? What do you need?’” Rachlin recalled in a telephone interview.

Schechter helped review the weekly press releases that she and others drafted, documenting the early stages of the campaign—mostly reports of arrests, torture, brainwashing, and deaths in custody—as they attempted to gain the attention of newspaper reporters and television producers. Western reporters based in China at the time were being inundated with propaganda portraying Falun Gong adherents as dangerous and unhinged, and those who attempted to seriously pursue the story were often harassed and sometimes forced out of the country.

“We were novices, all new at this, but he'd been doing it for 40 years,” Rachlin said. “He had done advocacy and causes, so he was familiar with the venues and how to make sure people understood who we were.”

Schechter went on to write a book, “Falun Gong’s Challenge To China,” published in early 2001, and to direct a documentary of the same title. The book was the first major treatment of the practice on the market and was widely referenced in later academic literature. In it Schechter sought to dispel some of the myths and propaganda that had been promulgated about Falun Gong by Chinese authorities.

His film, according to a review by The New York Times, “provides ample testimony that, contrary to China’s position, Falun Gong is not a cult; and photographic evidence and oral statements support Falun Gong’s contention that China’s government has tortured its followers.”

Stephen Gregory, publisher of the New York English-language edition of Epoch Times, said that Schechter “has been a friend to the Epoch Times.” The newspaper regularly published his syndicated “news dissector” columns, and Schechter delivered a rousing address to newspaper staff in 2009, during which he expressed his admiration for the paper’s mission.

“Danny lived and breathed the news, and he had a passion for telling things the way they really are,” Gregory said. “He had a hatred for the fake and cant that he saw dominating the news scene today. He was a tireless writer and filmographer and had a knack for asking the uncomfortable questions about big events that others didn’t want to have asked: whether it was about Wall Street and the collapse of the economy in 2009, or the persecution of Falun Gong, or the career of Nelson Mandela.”

Danny Schechter is survived by his daughter, Sarah Schechter, formerly a production executive at Warner Bros. and currently the president of Berlanti Productions based in Los Angeles.

In the weeks before his death, Schechter often invited his friends and relatives to visit him at his capacious loft on 23rd Street in Manhattan. “He was very positive. He had pulled through the first phase of treatment, but said ‘I don’t know, I could die any day,’” according to Gail Rachlin, who saw him for the last time several weeks ago. “‘People are coming to see me. It’s a great feeling on my way out,’” she recalled him saying, “’that this is it, and that I have friends around.'”