WASHINGTON—In recent years, there has been an upsurge of discussions and legislation favoring criminal justice reform. Many experts and policymakers question whether long sentences for nonviolent drug abuse offenders is worth the annual cost to house, feed, and guard an inmate, which is about $30,000. But the benefits of reducing prison populations and other criminal justice reforms are not limited to fiscal considerations, extending to better, more humane ways for offenders to reenter their communities.

There is strong bipartisanship in demanding reform. Beginning with Texas in 2007, more than 30 states have passed legislation, by lopsided votes, approving sentencing and corrections reforms.

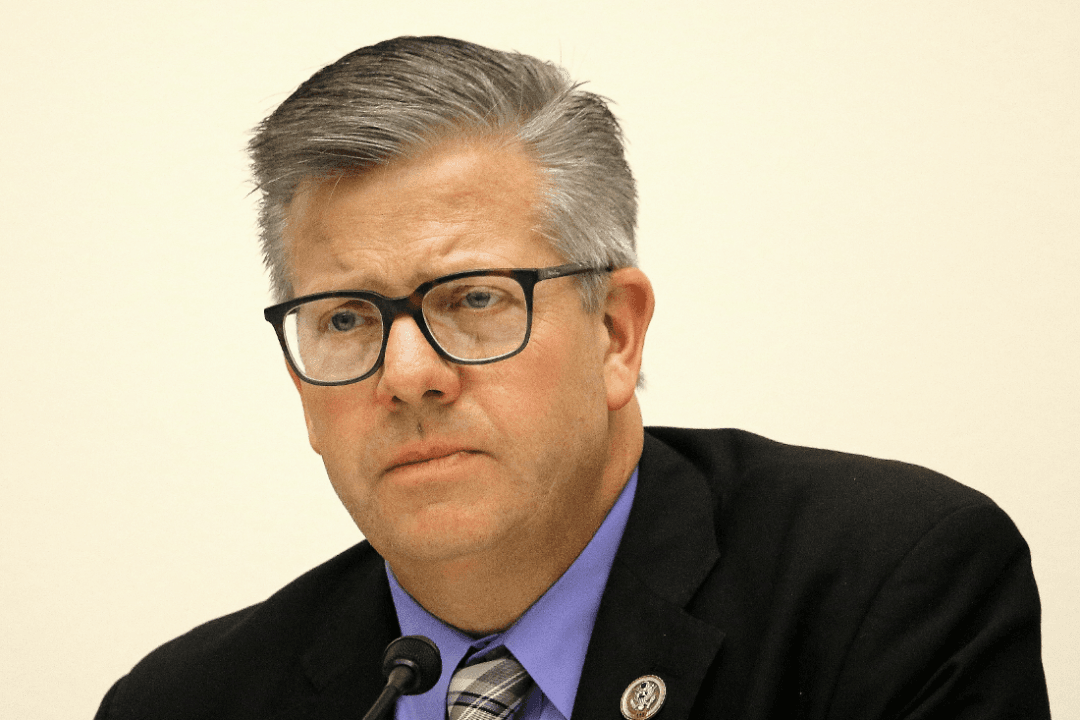

On Sept. 9, the American Enterprise Institute, a Washington-based conservative think tank, held a forum to discuss criminal reform, and some options based on the latest research on reducing incarceration, effective policing, rehabilitation approaches, and strengthening relationships between law enforcement and communities.