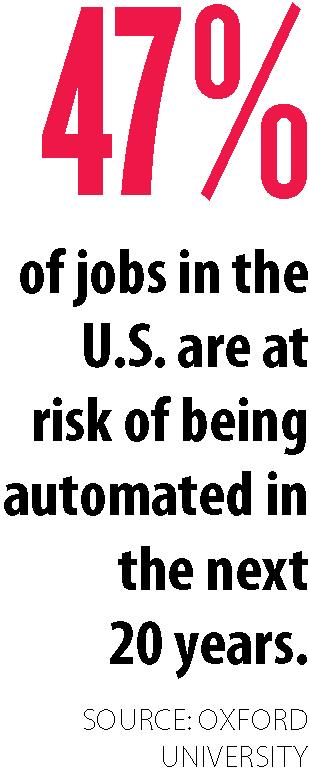

Despite the temporary injection of confidence in the American economy brought about by the election of President Donald Trump, major structural problems continue to lurk beneath the surface. These trends, decades in the making, are so entrenched and intractable that even Trump’s boldest plans may not be able to resolve them.

*

Valentin Schmid is a former business editor for the Epoch Times. His areas of expertise include global macroeconomic trends and financial markets, China, and Bitcoin. Before joining the paper in 2012, he worked as a portfolio manager for BNP Paribas in Amsterdam, London, Paris, and Hong Kong.

Author’s Selected Articles