New technology capable of sending high-intensity laser beams through the atmosphere much farther than was ever possible before could one day be used to guide lightning away from buildings.

Currently, high-intensity lasers, produced with modern technology essentially disappear over distances greater than a few inches or several feet at best when focused tightly, due to diffraction—the same effect that makes a stick seem to “bend” when dipped into water. This makes them too short-ranged for applications such as diverting lightning.

The breakthrough lies in embedding the primary, high-intensity laser beam inside a second beam of lower intensity. As the primary beam travels through the air, the second beam, called the dress beam, refuels it with energy and sustains the primary beam over much greater distances than were previously achievable.

“Think of two airplanes flying together, a small fighter jet accompanied by a large tanker,” says Maik Scheller, an assistant research professor in the College of Optical Sciences at the University of Arizona, who led the experimental work published in Nature Photonics.

“Just like the large plane refuels the fighter jet in flight and greatly extends its range, our primary, high-intensity laser pulse is accompanied by a second laser pulse—the ‘dress’ beam—which provides a constant energy supply to compensate for the energy loss of the primary laser beam as it travels farther from its source.”

The development of the new technology was supported by a US Department of Defense grant awarded to a group of researchers led by Jerome Moloney, professor of mathematics and optical sciences. Moloney is heading up research to investigate ultra-short laser pulses, focusing on their effects in the atmosphere and ways to improve their propagation over many kilometers.

Billionth of a Millionth of a Second

Improved understanding of the pulses would create the groundwork for a new class of robust laser beams that are more effective in overcoming scattering caused by atmospheric turbulence, water droplets in clouds, mist, and rain, Moloney says. Such beams could be used in detection systems reaching over long distances.

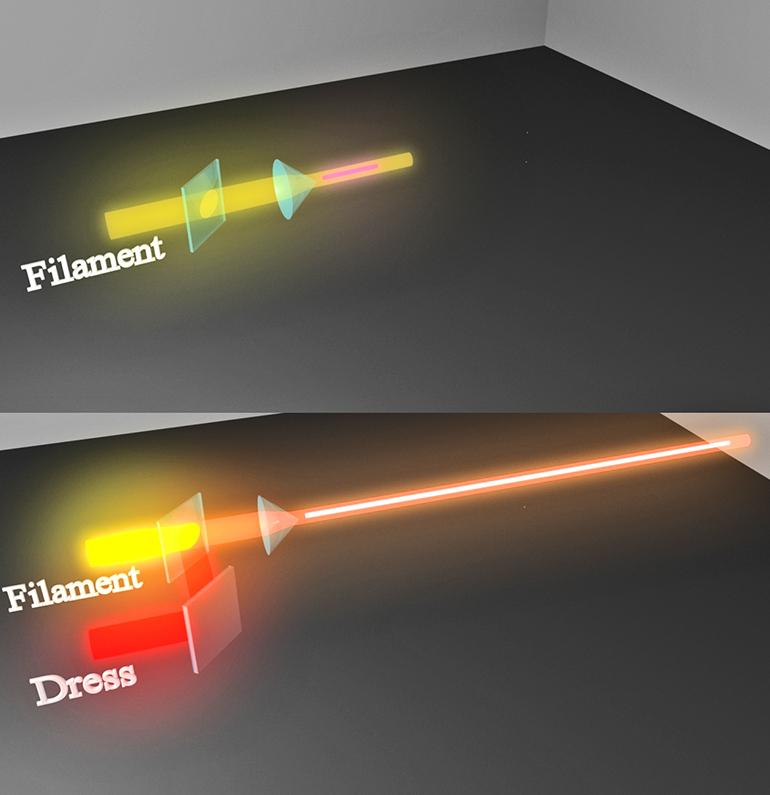

The top image shows the case of the intense central beam alone. The beam is focused and a short filament results and the plasma channel dissipates rapidly. In the bottom figure, the beam is accompanied by the dress beam. The filament and the plasma channel is extended manifold. (University of Arizona)

Unlike conventional lasers, the laser bursts used in the new research pack extremely high energy into very short timespans on the order of a femtosecond; a billionth of a millionth of a second.

“Usually, if you shoot a laser into the air, it is limited by linear diffraction. But if the energy is high enough and condensed into a few femtoseconds, creating a burst of light of extremely high intensity, it propagates through the air in a different way due to self-focusing,” Scheller says. “The problem is that as it also ionizes the air and creates a plasma, so the laser loses energy.”

In other words, at some point the airplane runs out of fuel.

The filament doesn’t go very far because of the energy loss that ultimately causes the laser to dissipate. The dress beam used in Scheller’s research overcomes this limitation.

Channel of Plasma

“We use two different kinds of beams: one is a focused central beam of high intensity that creates the filament. The other that surrounds it has a long range of almost constant intensity. As a result, the dress beam propagates in a nearly linear manner.”

Similar to the principle of noise-canceling headphones, the energy loss of the primary laser beam and the energy supply from the dress laser beam cancel each other out. In the lab, the researchers were able to extend the range of filament lasers tenfold, from about 10 inches to 7 feet.

Simulations performed by Matthew Mills at the University of Central Florida have shown that by scaling the new laser technology to atmospheric proportions, the range of the laser filaments could reach 50 meters (165 feet) or more.

As the filaments travel through the air, they leave a channel of plasma in their wake—ionized molecules stripped of their electrons. Such plasma channels could be used as a path of least resistance to attract and channel lightning bolts. Ultimately, this technology could be used to control lightning bolts during a thunderstorm and steer them away from buildings.

Source: University of Arizona. Republished from Futurity.org under Creative Commons License 3.0.