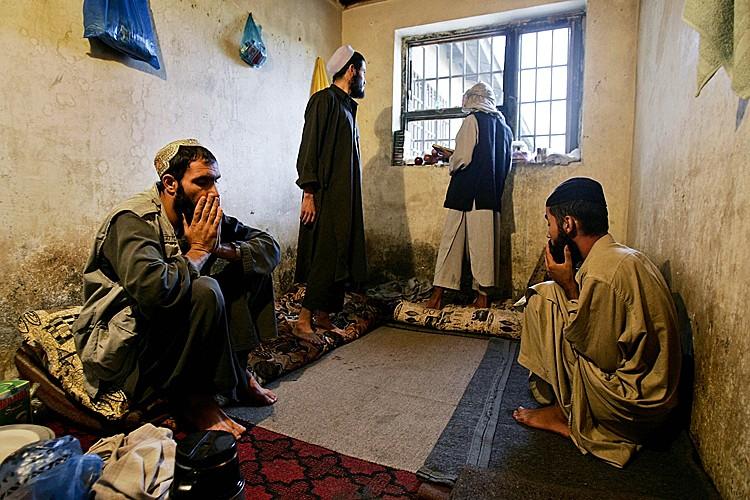

Corruption Turning Afghan Prisons Into Taliban Bases

The confinement of Afghanistan’s Pol-e-charki prison amounts to little more than protective walls for the Taliban rendering them untouchable from the war raging outside.

|Updated:

Joshua Philipp is senior investigative reporter and host of “Crossroads” at The Epoch Times. As an award-winning journalist and documentary filmmaker, his works include “The Real Story of January 6” (2022), “The Final War: The 100 Year Plot to Defeat America” (2022), and “Tracking Down the Origin of Wuhan Coronavirus” (2020).

Author’s Selected Articles