Feb. 8 is Chinese New Year—the biggest holiday of the year for Chinese families. Thus the end of the year is usually when migrant workers in China start heading home for family gatherings and reunion feasts. But many have had to delay their return dates this year after not getting paid for months of work, especially those in the construction industry.

“One day passes after another; I haven’t got my salary for four months,” Luo Yixue, a migrant worker from Sichuan Province, told Xinhua, China’s official state media. With wages long overdue, Luo can’t even pull enough money together for a ticket home.

Over two weeks in December, the High People’s Court in Henan, a province in central China, heard over 6,700 cases involving about 10,000 migrant workers who were owed a total of $48 million in back wages.

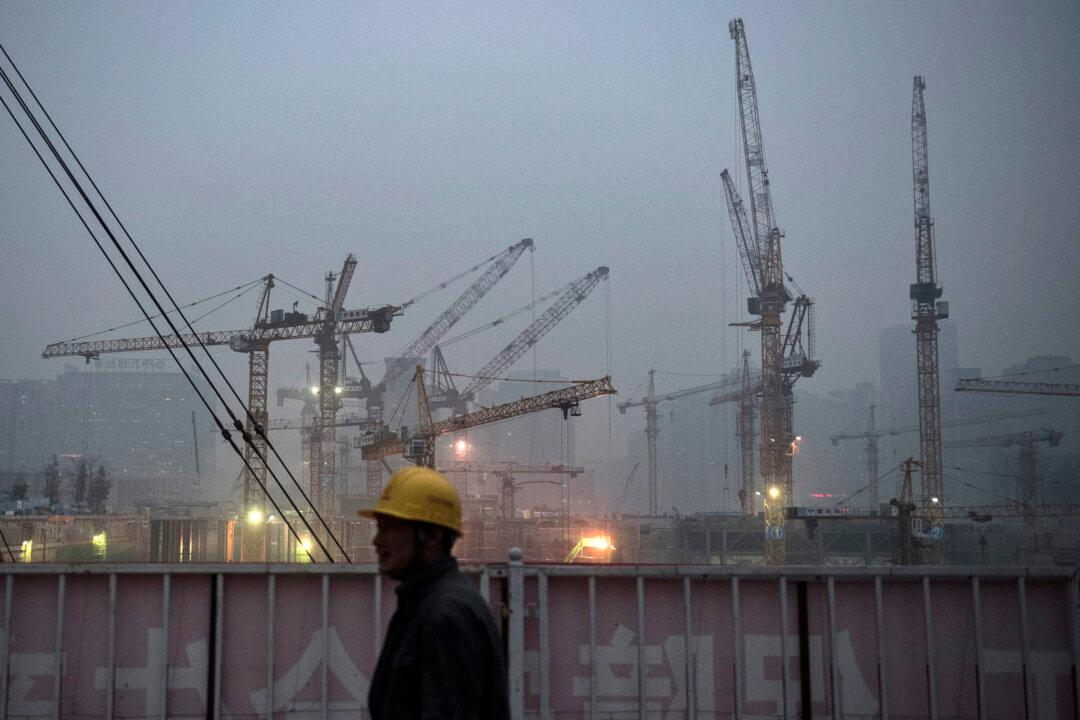

Two nine-story commercial buildings near completion stand imposingly on a street in Zhengzhou City. At their base, are the shabby homes of the construction workers who erected them. Luo and the others haven’t been paid since Aug. 20, and although the construction work has been done for four months, they haven’t left, still waiting for the over $9,000 they’re collectively owed.

“My boss has only given me $154 in living expenses since August,” said Luo. “We can only buy those cheap vegetables, or pick up discarded vegetable leaves in the market. Every one of us spends less than $1.54 a day.”

Luo says he feels sad when looking up at the new buildings, in contrast to the happiness he felt when the project began, knowing money would be coming in. He never expected that he wouldn’t be paid and his labors would be in vain.