There are many reasons for the most recent financial meltdown, but what runs through every economic and financial analysis is the subprime mortgage debacle, which resulted in many failures of small community banks.

Large and small banks took too much risk, were lax in their credit analysis, or even lacked the skills for a thorough credit analysis of the borrower. People who couldn’t afford a house, or at least the size of the house purchased, were provided a loan with an adjustable interest rate that screamed future foreclosure. All the warning signs were ignored.

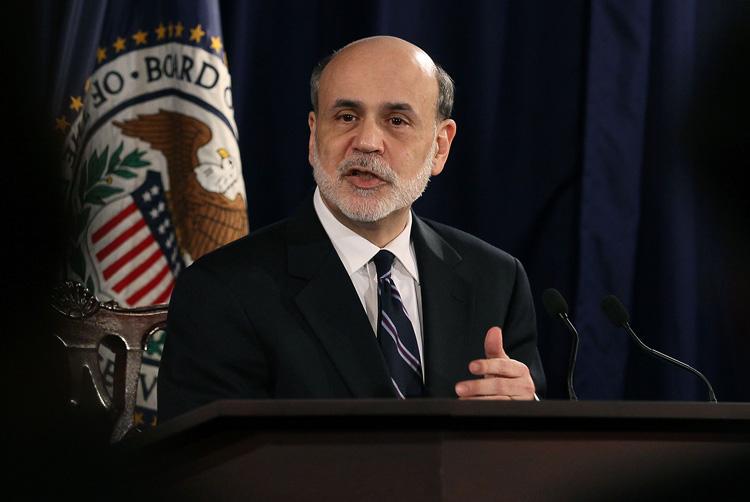

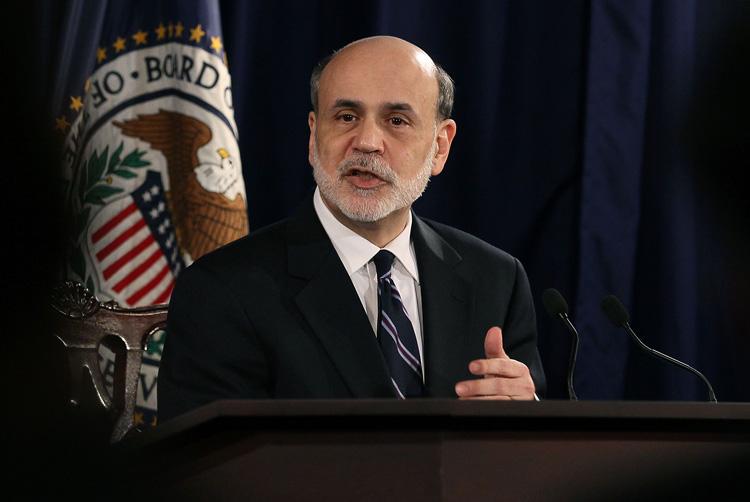

In 2006, mortgage defaults began to materialize, with 11 percent of subprime mortgages with adjustable interest rates outstanding in that year going sour. There were 310,000 foreclosures alone during the last quarter of 2006, with about 50 percent being subprime mortgages, according to a 2007 speech by Ben S. Bernanke, Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

At the end of March, there were approximately 1.33 million foreclosed homes in the market, according to the Realty Trac website. There were about 3.5 million foreclosed homes from September 2008 to March 2012, according to CoreLogic, an information and data analysis provider.

Sales of foreclosed homes have slowed down, with March data indicating that “foreclosure sales continued to behave somewhat erratically, dropping to their lowest level since December 2010,” according to the Lender Processing Services Inc. website.

Bank Failures Adding Pressure

Since 2000, a total of 466 banks have failed with the largest number, 154 banks, failing in 2010 and 140 in 2009. So far in 2012, 23 banks have failed, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC).

At the end of February, there were 960 problem banks on the unofficial problem bank list published by the Calculated Risk website. As of December 2011, there were 813 institutions on the FDIC Problem Bank List, down from the 884 at the end of 2010. In 2006, there were only 50 troubled banks, while the number increased to 252 banks by 2008, jumping to 702 banks in 2009.

Although the FDIC maintains a list of problem banks, it “does not publicize the list for fear of causing a run on the banks involved,” according to an article on the Problem Bank List website.

Additionally, the FDIC cost for failing banks is very high, and it lacks the funds in the Deposit Insurance Fund. The FDIC Deposit Insurance Fund is funded by the banks and pays out $250,000 to depositors of each failed FDIC insured bank. At Dec. 31, 2011, the fund had a balance of $9.2 billion.

“A number of large banking failure[s] could deplete the entire insurance fund,” suggested an article on the Problem Bank List website.

Gradually Closing TARP

“There are still 343 banks remaining in TARP’s [Troubled Asset Relief Program] Capital Purchase Program. Most of them are smaller, community lenders,” according to a U.S. Department of Treasury announcement on May 3.

The U.S. Treasury announcement, “Winding Down TARP’s Bank Programs,” suggested that it is seriously considering three options to wind down the program.

The first option is to wait for repayment, which might take quite some time. Community banks, which are smaller banks with less than $10 billion in assets, may not have the funds for a long time to repay Treasury—this may not be a realistic option. Secondly, the bank could be reorganized, which most likely is followed by a merger. Lastly, the Treasury could sell the preferred stock in the market.

The option used will depend on market conditions once a decision is imminent.

Selling stock might not be very successful, as community-based banks are generally not known outside their area of operation, and thus a larger investment community is not readily available or willing to become an investor.

“The government shouldn’t be in the business of owning stakes in private companies for an indefinite period of time. And replacing temporary government support with private capital is an important part of continuing to restore financial stability,” the Treasury announcement concluded.

The Treasury held a preferred stock auction in March, increasing taxpayer funds by over $362 million. These auctions may also be a good venue for divesting community bank preferred stocks, garnering a larger population of investors.

The going price of the preferred stock has already been set, given that the value of the banks has decreased. However, the announcement argues that the TARP bank program has already made $19 billion for the taxpayer, and thus the profit for the taxpayer can only increase and not decrease.

“The sale prices may be less than the original par value. But we have already estimated that the value of these investments is less than par in our budget projections, and we'll only sell above a pre-set reserve price in order to best protect taxpayer value,” according to the Treasury announcement.

Refinancing Small Banks Option

“As of March 31, 2012, 351 regional and community banks remained in CPP [Capital Purchase Program]. That’s in addition to 83 financial institutions in TARP’s Community Development Capital Initiative (‘CDCI’), for a total of 434 still in TARP,” according to an April 25 SIGTARP report titled “TARP and SBLF [Small Business Lending Fund]: Impact on Community Banks.”

Community banks are smaller sized banks that may operate in one or perhaps up to four states or perhaps just in a county. The Federal Reserve System acknowledges that any bank with up to $10 billion in assets is such a bank.

However, there is no general agreement regarding the definition among those who deal with smaller sized banks. The Independent Community Bankers of America, representing the interest of community or small-sized banks, accepts banks with up to $17 billion in assets into its fold.

A total of 137 small banks were allowed to exit the TARP program, not by repaying the TARP program out of their pocket, but through refinancing under another government program. They transferred from the CPP into the SBLF program, which was enacted under the Small Business Jobs Act of 2010 and administered by the U.S. Treasury.

“Many community banks in CPP looked to SBLF as a way to refinance and exit TARP. Treasury received 935 applications to the [SBLF] program, of which 320 were from TARP banks,” stated the SIGTARP report.

The 137 community banks swallowed two-thirds, $2.7 billion, of the SBLF funds. Western Alliance Bancorporation, based in Phoenix, Ariz., received $141 million, $1 million more than it had received under TARP. The second largest recipient was Plains Capital Corp. based in Dallas, Texas, which received $114.1 million, significantly more than it received under the TARP program.

According to investment experts from the firm Raymond James and the Barack Ferrazzano Financial Institutions Group, investors need to inject $23 billion into the small banks that are still in the TARP program to keep them alive. Other investment experts, such as StoneCastle Partners, suggest that small-sized banks need at least $90 billion before they can exit TARP.

Investment experts advise that owners of community banks should first borrow among themselves. Such an action would show investors that the owners are convinced of the continued existence of the bank, thus encouraging investors to be more willing to invest in the bank.

“Small banks that are successful in raising new funds ‘often first pass the hat around the boardroom table,’” suggested investment experts in the SIGTARP report.

The Epoch Times publishes in 35 countries and in 19 languages. Subscribe to our e-newsletter.