BERLIN—The pioneering lander Philae completed its primary mission of exploring the comet’s surface and returned plenty of data before depleted batteries forced it to go silent, the European Space Agency said Saturday.

“All of our instruments could be operated and now it’s time to see what we got,” ESA’s blog quoted lander manager Stephan Ulamec as saying.

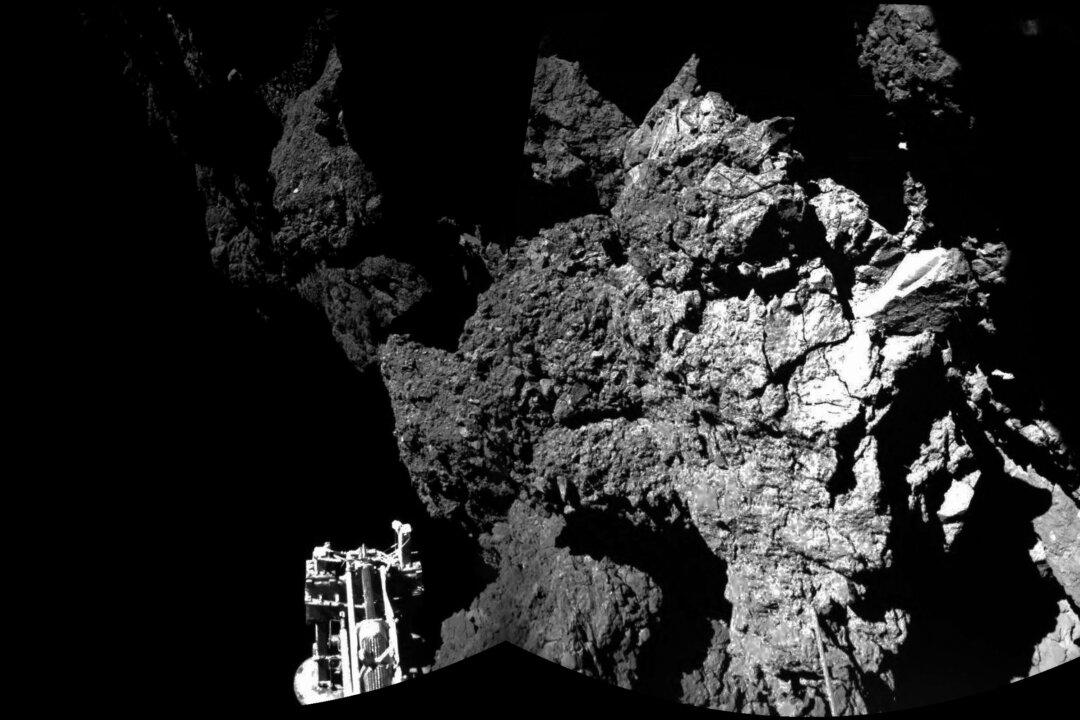

Since landing Wednesday on comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko some 311 million miles (500 million kilometers) away, the lander has performed a series of scientific tests and sent reams of data, including photos, back to Earth.

In addition, the lander was lifted on Friday by about 4 centimeters (1.5 inches) and rotated about 35 degrees in an effort to pull it out of a shadow so that solar panels could recharge the depleted batteries, ESA’s blog said.

[aolvideo src=“http://pshared.5min.com/Scripts/PlayerSeed.js?sid=1759&width=480&height=300&playList=518516962&responsive=false”]

ESA spokesman Bernard von Weyhe on Saturday confirmed the lander’s difficult rotation operation. It’s still unclear whether it succeeded in putting the solar panels out of the shade.

Even if the lander was rotated successfully and is able to recharge its batteries with sunlight, it may take weeks or months until it will send out new signals. Regular checks for signals will continue.

The agency did not schedule any media briefings on Saturday.

ESA’s mission control center in Darmstadt, Germany, received the last signals from Philae on Saturday morning at 0036 GMT (7:36 p.m. EST Friday). Before the signal died, the lander returned all of its housekeeping data as well as scientific data of its experiments on the surface — which means it completed the measures as planned, the ESA blog said.

During a scheduled listening effort on Saturday at 1000GMT, ESA received no signals from Philae, ESA’s mission chief Paolo Ferri told The Associated Press.

“We don’t know if the charge will ever be high enough to operate the lander again,” Ferri had told The AP ahead of the 1000GMT (5 a.m. EST) listening time. “It is highly unlikely that we will establish any kind of communication any time soon.”

Now it’s up to ESA’s team of scientists to evaluate the data and find out whether the experiments were successful — especially a complex operation Friday in which the lander was given commands to drill a 25-centimeter (10-inch) hole into the comet and pull out a sample for analysis.

“We know that all the movements of the operation were performed and all the data was sent down” to ESA, Ferri said Saturday. “However, at this point we do not even know if it really succeeded and if it (the drill) even touched the ground during the drilling operation.”

Material beneath the surface of the comet has remained almost unchanged for 4.5 billion years, so the samples would be a cosmic time capsule that scientists are eager to study.

The lander did already return images of the comet’s surface that show “it is covered by dust and debris ranging from millimeter to meter sizes,” while “panoramic images show layered walls of harder material,” ESA’s blog stated.

The science teams are now studying their data to see if they have succeeded in sampling any of this material with Philae’s drill.

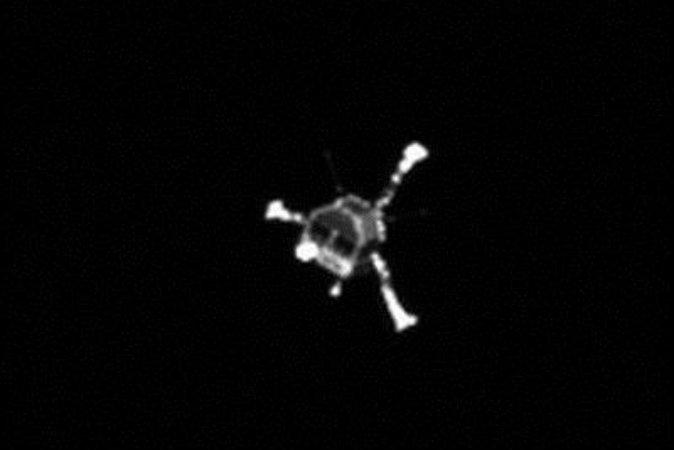

Beyond analyzing the new data, scientists are also still trying to find the exact spot where Philae landed on Wednesday.

“The search for Philae’s final landing site continues, with high-resolution images from the orbiter being closely scrutinized,” the blog said.

Scientists hope the $1.6 billion (1.3 billion-euro) project will help answer questions about the origins of the universe and life on Earth.

One of the things scientists are most excited about is the possibility that the mission might help confirm that comets brought the building blocks of life — organic matter and water — to Earth. They already know that comets contain amino acids, a key component of cells. Finding the right kind of amino acids and water would be an important hint that life on Earth did come from space.

“The data collected by Philae and Rosetta is set to make this mission a game-changer in cometary science,” Matt Taylor, ESA’s Rosetta project scientist, was quoted as saying on the blog.

From The Associated Press