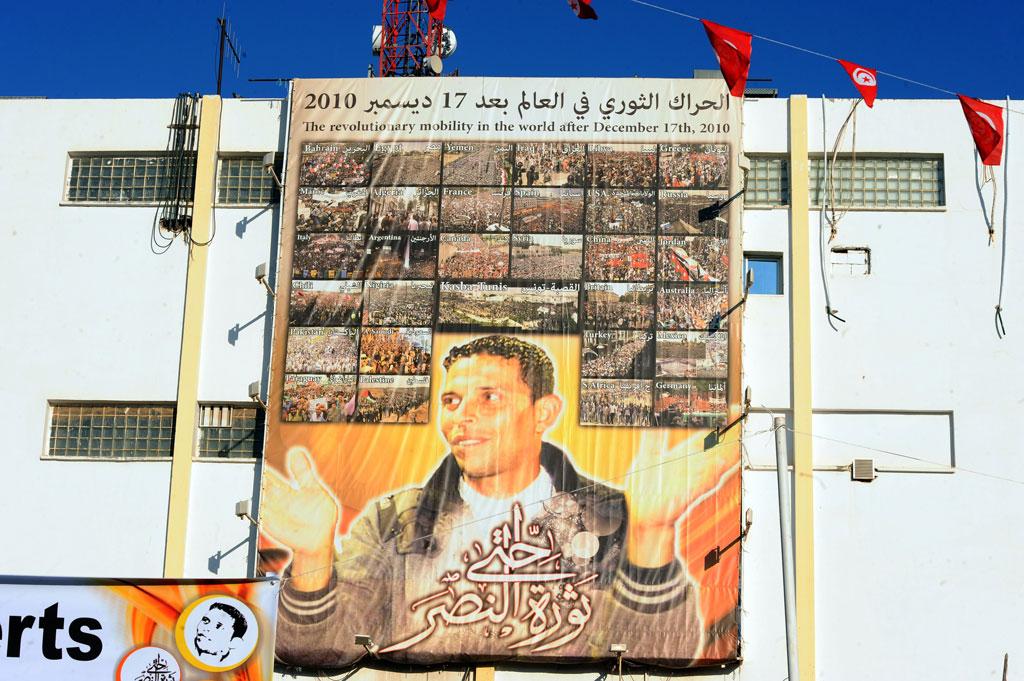

A desperate Tunisian fruit and vegetable vendor immolated himself on Dec. 17, 2010, setting off a chain of demands for dignity and a better life. The past four years in the Arab world have seen vast turmoil, and the end is not yet clear. The Arab countries of the Middle East and North Africa are passing through their most abrupt and historic experience since decolonization and independence following World War II.

It is natural that Americans want to see people succeed in freeing themselves from authoritarian rule. But demands for rapid change that start with sweeping idealism often end badly, as they did for early twentieth-century Russia. Or, as was true for late eighteenth-century France, a positive outcome may not emerge before decades of bloodshed and destruction.

After a long period of stagnation in the development of political institutions, Arab countries were in for a rough ride. Now that we are into the fifth year of dramatic change, the American public and American policymakers can begin to draw some educated lessons about what it all means. The following are not meant to exclude others.

First: One swallow does not make a spring. Premature judgments about the durability of liberal Arab rebellions fulfilled wishes on the part of the Arab and Arab-American intelligentsias, the Western media, and far too many Middle East academic experts. Next time, hold the applause until the dust settles.

Second: Democracy is hard. After the end of British rule over the 13 colonies in 1779, it took seven years to get a system that could elect national leaders. Our founders did so partly by brushing many disputes under the rug of compromise. Seventy years later we had to fight a terrible civil war to resolve some of those issues of democracy, and we are still striving today for a more perfect union. No one should have expected quick success for similar ventures in Arab countries with meager historical experience in self rule. Compromises, often messy ones, have to be a part of the process of reaching a more democratic and pluralistic equilibrium.

Third: Sudden overthrow of autocratic regimes was likely to lead to periods of disorder and even chaos. To quote William Butler Yeats, writing after World War I:

Things fall apart; the center cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world.

The blood dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Before the West is too sure about the formula an Arab government should follow, let it remember the history of the supposedly advanced nations of twentieth-century Europe. Gradual and evolutionary change may not capture media eyeballs and satisfy our romantic aspirations, but it has clear advantages.

Continue reading this article at the Middle East Institute. Republished with permission from the Middle East Institute.

David Mack is the former Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Near East Affairs (1990-1993) and US Ambassador to the United Arab Emirates (1986-1989). Mack’s US diplomatic assignments included Iraq, Jordan, Jerusalem, Lebanon, Libya, Tunisia, and Saudi Arabia. Mack has extensive experience and knowledge on Iraq, Libya and UAE. He also comments on US Middle East policy and the security of the Arabian Peninsula and Persian Gulf region.