HELPER, Utah—Roman Vega Jr. had just graduated from high school when he first encountered the underground “long wall” at the coal mine where his father worked in Colorado.

It was not a place for the timid or the claustrophobic, Vega said. The work was loud, dusty, and hazardous.

“You could see how big it was and how deep underground you had to go to get to these places,” Vega, who is from Helper, Utah, said. “You watched these [machine] blades just tear through the mountain.”

He said he could hear the mountain eerily vibrate or “sing” through the large bolts driven into the stone to prevent the mine’s roof from collapsing.

Vega said the experience overwhelmed him and he told his father that he could not mine for a living.

“I'd prefer to jump out of airplanes and get shot at,” he said.

He then enlisted in the Army and served four combat tours in Iraq.

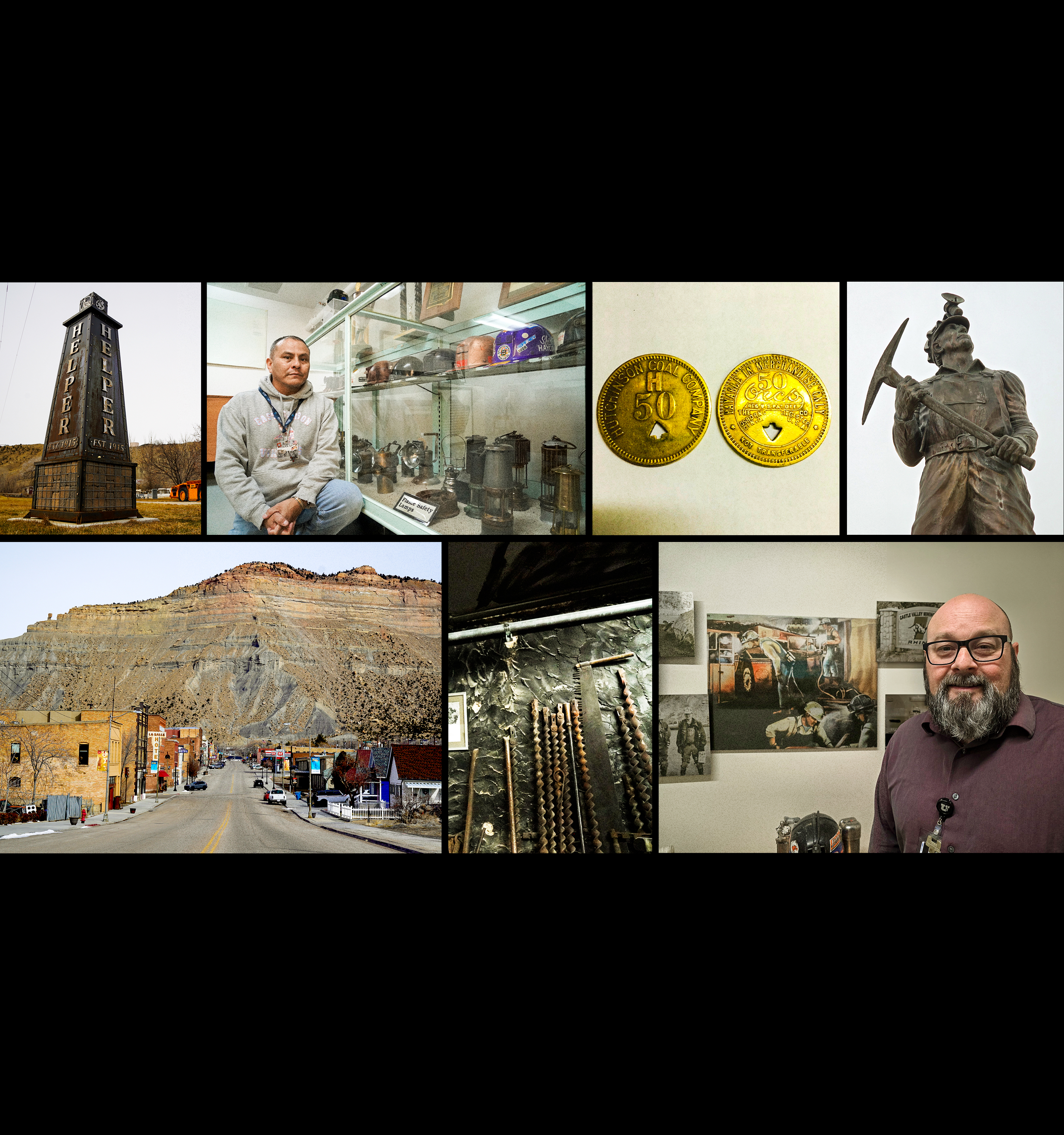

The town, established in 1881, was named after the “helper” locomotive that helped trains climb Price Canyon’s sheer slopes. It remained a significant hub for coal transport well into the 20th century.

“I’m not a coal miner, but I do know the history of coal mining in this area,” Vega said. “There’s a lot of coal—a lot of value in these mountains.”

Today, the coal mining rail cars still rumble through Helper (population 2,126), but the town is no longer the same diverse coal community it once was.

At one point, more than 20 different languages were spoken there.

Although the town looks largely the same now as in photos and postcards from nearly a century ago, its focus has shifted toward tourism, history, culture, and the arts.

More than a dozen shops and restaurants line Main Street, set against the backdrop of the steep shale and sandstone Book Cliffs mountains over Helper.

“The great thing about Carbon County is it has some of the purest, cleanest coal out there,” Vega told The Epoch Times. “But there’s the difficulty getting to it.”

Much of the coal remains deep underground, requiring expensive heavy equipment and highly trained workers to extract it.

Officials in the coal industry have reported a decline in demand for coal in Utah and other regions across the country. They are facing several challenges, including difficulties in finding workers, the closure of existing mines, and a lack of new mines opening.

These issues are compounded by government regulations related to carbon emissions, which are affecting the entire industry.

“Most of Utah’s coal industry has already shut down; all of the mines where we represented the workers are now closed,” Phil Smith, spokesman for the United Mine Workers of America, said.

Smith said Utah coal is exclusively utility-grade “steam coal,” which is not suitable for steel production. Moreover, the domestic market for steam coal is relatively weak.

“I can’t see any company spending the significant amount of money it would take to open a new mine without a robust market,” he said.

In 2020, the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) reported that 40 coal mines opened in the United States, while 151 mines were either idle or closed.

By the end of that year, the number of coal-producing mines had decreased to 551, following an industry peak in 2008.

Most mines in Utah are underground.

The EIA observed that the only active surface coal mine is located in the south, near the Arizona border, while most of Utah’s coal is used locally for electricity generation.

Wyoming is the leading producer, accounting for 41.2 percent, followed by West Virginia at 14 percent, Pennsylvania at 6.7 percent, Illinois at 6.3 percent, and Kentucky at 4.8 percent.

Utah currently holds about 1 percent of the nation’s coal reserves and accounts for 1.2 percent of U.S. coal production.

In 2021, the United States imported nearly $8.3 billion worth of steel products from Canada, which represented approximately 25 percent of the total value of steel product imports for that year.

“President Trump is taking action to end unfair trade practices and the global dumping of steel and aluminum,” the White House said in a statement. “Foreign nations have been flooding the United States market with cheap steel and aluminum, often subsidized by their governments.”

After Utah’s coal production rose in 2019 because of increased demand from the overseas export market, it later declined to its lowest level in nearly 50 years, the EIA reported.

Temporary closures and production issues at the Lila Canyon, Skyline, and Coal Hollow mines partly caused this decline.

Additionally, Utah’s coal output dropped, and mines shut down because of reduced demand for coal from the U.S. electric power sector.

“No new coal-fired power plants are being built in the United States, and none are planned,” Smith said.

“Most utilities have announced closure dates for almost all their fired plants, although some are extending those dates because of concerns about baseload power in areas where we are seeing significant construction of data centers.”

Reliable Resource

The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis noted that the United States is swiftly transitioning from coal-fired power plants to renewable energy sources.The organization projected that by the end of 2026, the country will have reduced its coal generation capacity by 50 percent compared with its peak level in 2011.

Currently, fewer than 200 large coal-fired plants do not have retirement dates, and 118 of these plants are at least 40 years old.

Wind and solar energy account for about 19 percent of the total energy supply; nuclear power makes up 21 percent.

“As long as we’re using coal, there will be a market for coal,” Johnson told The Epoch Times. “As long as we have a steel industry, there will be a market for metallurgical coal.”

He added: “At some point in time, we’ve got to come to reality: If we’re going to have baseload power, it’s going to be oil, gas, coal, or nuclear. The economies of scale will be the judge.”

Ohio is the nation’s 13th-largest producer of bituminous coal and currently holds more than 4 percent of the country’s recoverable coal reserves, the EIA noted.

In 2022, the state operated seven surface coal mines and three underground mines. Ohio used about half the coal it produced, while the remainder went to neighboring Kentucky and West Virginia for energy production.

“We want baseload power,” Johnson said. “We want to promote baseload power generation. I don’t expect that to be coal when natural gas is more economical to build and operate.

“To be quite honest, most of the coal-fired [plants] we know to be dinosaurs. But they’ve been maintained well. They’re meeting their [Environmental Protection Agency carbon emissions] rates.”

Johnson said the recent boom in natural gas production in Ohio should alleviate some of the downturn in coal production.

“We’re sitting on the Saudi Arabia of natural gas right here in America,” Johnson said. “There’s crude oil mixed in with this.”

The EIA found that in 2023, Ohio produced 97 percent of its gross natural gas withdrawals from shale gas wells.

By August 2024, the state’s seven ethanol plants could produce 765 million gallons per year.

Johnson said federal energy policy significantly influences what coal producers and other fossil fuel producers are allowed to do.

“It’s yet to be seen what our new administration is going to do,” Johnson said. “If you want my personal opinion, coal will never rebound to the level it once was.

“Here’s the thing—India and China still burn coal at a rapid rate. We’re exporting coal, and that maintains our tonnage to some degree. At the same time, it has to be economical tonnage. You can’t mine small seams that aren’t economical.”

Moreover, Johnson said, the coal mining workforce has dropped significantly.

The coal mining sector in the United States employed 45,476 people in 2023, with 62 percent working underground, according to market trend analyst Statista.com.

The site noted that this number marks a significant decline from 92,000 employees in 2011.

While Johnson never met his grandfather, Ray Johnson, he said he was “a West Virginia coal miner” who lived in a company coal town and died of a burst appendix at age 34.

Back then, the coal company “owned everything,” Johnson said.

It produced its own currency, or “scrip,” which was used to purchase goods at company-owned stores. Johnson keeps examples of his grandfather’s scrip on the desk in his office at the Ohio Statehouse.

“All I heard from my Dad were the many stories of how they struggled to eat,” Johnson said of his relatives who worked in the coal mines. “The coal company owned the house they lived in.

“In those days, the coal companies thought more of their mules than they did the miners. [The companies] had to buy the mules.”

Johnson said his father’s uncle, Russ, was a union organizer who “settled things with ... fists” but made sure that his family had a place to live in the coal town.

Uncertain Futures

Michael Kourianos, the mayor of Price, Utah, supervises PacifiCorp’s coal-fired energy facility in Huntington, Utah, which is located in Emery County.“I’m like the CEO of Price City—we buy power and we sell power,” Kourianos, whose father and brother were coal miners, said.

As mayor, Kourianos has the opportunity to observe the production, procurement, and consumption aspects of energy.

With 2.1 million customers, PacifiCorp is the largest grid operator in the western United States.

In 2023, the company announced that the Huntington plant would close at the end of its operational life, projected for 2036.

Kourianos said Utah’s fast commercial and residential growth, along with the rising demand for energy, renders the closure of the state’s coal plants increasingly impractical.

“That tells you there’s not enough generation in the system for the demand,“ he said. “Utah is growing substantially. They have to balance [supply and demand for energy].”

Kourianos said he does not have a preference when it comes to energy production.

“Whatever low-cost energy we can produce, I’m all in,” he said. “What’s the most economical and sustainable for energy? That is the biggest thing people need to realize in Utah ... the cost of energy is really low. It’s attracted a lot of industry to the state in the growth that we have.”

Coal production is another story.

Kourianos said Carbon County has not mined any coal since the last mine closed in about 2020. Four mines, including Fossil Rock, continue to operate in Emery County, located 59 miles south of Carbon County.

The future of coal seems to be caught between opposing political agendas, he observed.

One side advocates for increased exploration and expansion of energy resources, including natural gas and oil, while the other emphasizes an environmental need to phase out fossil fuels.

He likened the situation to a “roller coaster ride,” highlighting the lack of consistency between different administrations in Washington.

“If you’re letting environmental [agendas] drive the decisions ... we’re all going back to candles,” Kourianos said.

Energy Emergency

On Jan. 20, Trump signed an executive order that declared a national energy emergency, emphasizing a renewed commitment to fossil fuels.The directive underscored the need for domestic exploration and the expansion of critical resources, including natural gas, petroleum products, biofuels, geothermal energy, hydroelectric power, and coal.

“Indeed, the focus appears to be entirely related to greater production of oil and natural gas,” Smith said.

“Opening up coal leasing on federal land sounds nice, but we don’t see where the market exists to purchase that coal, even if a company overcomes the permitting and financing challenges.”

Smith said reversing the Biden administration’s energy regulations for power plants that burn coal will provide some relief to current coal producers, although this is not the main issue.

“What is suppressing a long-term revitalization of the entire American coal industry are the decisions already made by the utility industry,” he said.

“The best thing the Trump administration and Congress could do to help the coal industry is make even more significant government investment in deploying commercial-scale carbon capture and storage technology, and soon.”

Without the widespread implementation of carbon capture technology at coal-fired power plants across the country, he said, the only viable market for coal will be exports, including both steam and metallurgical coal.

However, Smith said, this will only represent about 30 percent to 35 percent of current coal production.

Rep. Don Jones (R-Ohio) said he does not expect new coal-fired plant construction, primarily because of federal energy policy and market trends.

“In Ohio, you’re probably going to see a growth in natural gas-fired power plants,” Jones, the chairman of Ohio’s House Natural Resources Committee, said. “We’ve had a few of those built. They are cleaner burning than coal. At the same time, I will say that coal still generates a lot of electricity for the state of Ohio.

“Coal still has a place. I will never say we don’t need more coal-fired power plants because I think we do.”

Jones said the issue with renewable energy is that people think that we can “simply install a few solar panels and solve the problem” of energy production.

While small-scale wind and solar solutions can work for individual homes to some extent, he said, they are not sustainable or feasible for industrial manufacturing facilities.

“We are going to come to a point in our society when we finally realize we can’t just walk away from what we know works,” Jones said.

“We haven’t even talked about nuclear [power], which is the most stable baseload generation that we have—period,” he said. “But it’s expensive, and most people don’t want to have the conversation about nuclear.

“The cost of decommissioning [nuclear] facilities scares a lot of people—and it should—because it is expensive.”

Jones expressed his frustration that many coal-fired power plants have already gone offline as a result of the restrictive energy policies of the previous administration.

“So, it’s not like we can go back in and retool them—they’re gone,” he said. “That’s the sad reality. [But] as long as [coal producers] continue to make deals—and make money—that’s the name of the game.”

India was the largest recipient of U.S. coal, accounting for more than 24 percent of the exports, followed by Japan, the Netherlands, Brazil, and China.

In February 2020, Richmond, California, prohibited the storage of coal for export, citing potential contaminants such as dust.

The situation presented a major challenge for some U.S. coal producers, resulting in five lawsuits against the city’s ordinance.

The Long Wall

Vega said coal mining today is far more advanced than in the past, when unsafe working conditions and child labor were common.Although steam coal from Carbon County is of high quality, its dust is highly combustible.

On March 8, 1924, an explosion at the Castle Gate Mine resulted in the deaths of 172 individuals.

This incident was one of the worst mining disasters in Utah’s history, second only to the Scofield Mine explosion, which claimed the lives of more than 200 miners.

On Dec. 19, 1984, a fire at the Wilberg Mine in nearby Emery County killed 27 mine workers.

Vega said his father derived great satisfaction from working with the Twentymile Coal Co. in Colorado. His obituary noted that he set a world record for cutting coal during a 10-hour shift in 1998.

“Mining is not as easy as it sounds,” Vega said. “Now, you need a college education to work.”

A lot of the different equipment that miners use underground is highly technical, he said.

His father worked at the long wall—a site and process involving heavy machinery that extracts large rectangular slices of coal from deep underground.

Once mined, the coal is placed on conveyor belts and transported to the surface.

“The long wall machinery is quite sophisticated, and a lot of it is remote-controlled,” Vega said. “So there’s a lot of education that is needed.

“It’s a hazardous job. Mining disasters are bound to happen since you’re dealing with gas, you’re dealing with dust—anything can happen.”

Statista.com data show that there were 2,821 coal mining fatalities in the United States in 1910, compared with nine in 2023.

The significantly lower fatality rate indicates advancements in safety and equipment, despite the fact that coal mining remains a dangerous job, Vega said.

“There’s coal production that can go up and that can go down, and there’s layoffs,” he said. “My father—he eventually had to move to Colorado because the mines in Utah were not paying well.”

Labor of Love

Even with better wages, Vega said, coal mining still has health downsides.“Healthwise, you have to worry about black lung disease,” he said. “You have to worry about [accidents] underground. These are large pieces of coal cut with blades. You could have 1,000-pound chunks of coal thrown at you.

“If you get hit by something like that, it’s going to do some damage. You have guys with back injuries—shoulders. It’s just a dangerous job. People don’t do it because they want to; it’s because it’s something that they love. They’re passionate.”

Shawn Shipley, clinical outreach and development coordinator at Miners Hospital in Salt Lake City, said the hospital treats approximately 500 miners each year for various injuries and chronic conditions out of a total enrollment of 1,800 miners representing 19 mines.

Some patients present with hearing issues, and despite stricter safety precautions, miners still come down with serious lung ailments, Shipley told The Epoch Times.

Extended exposure to coal dust can cause scarring in the lungs, which can impair the ability to breathe.

Shipley said that once approved by the Miners Hospital, individuals with mining-related health issues can receive medical coverage through a trust fund at the University of Utah Health.

Black lung disease remains “very prevalent,” he said, and the number of cases is likely to increase with age and years of exposure in the mines.

“You’ve got to be highly trained to be underground to do what they do,” he said. “These guys are absolutely amazing, going down underground and doing what they do every day. They absolutely love it, and they wouldn’t change it.”

Vega said he views coal miners as unique, much like his father, who never grew tired of the work.

“People don’t do the job for the glory or money,” Vega said. “They do it because they love it. It’s what they do—generation to generation.”