During the Spring and Autumn period (770–476 B.C.), there lived an old man in the state of Song. He was very fond of monkeys and raised many of them in his home. He could communicate with the monkeys and they could also understand him.

The old man fed each monkey eight chestnuts every day, four at dawn and four at dusk.

However, the monkeys ate so much food that soon there was not enough left for his family. So, the old man was forced to decrease the amount of food he fed his monkeys.

He decided to give each monkey seven chestnuts a day.

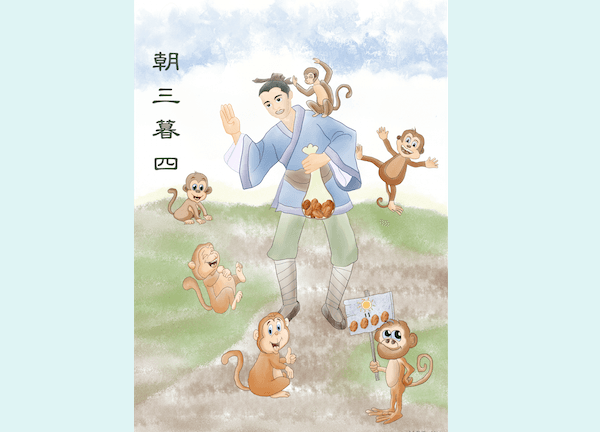

He gathered the monkeys together and informed them: “We are now short of food. From today on, I will give each of you four chestnuts at dawn and three chestnuts at dusk. I hope that is okay with you.”

Hearing this, the monkeys were quite upset. One elder monkey asked: “How come we get only three chestnuts in the evening? No!”

The other monkeys were angry that three chestnuts instead of four would be provided to each of them in the evening.

So the old man told them, “Well, then, each of you will get three chestnuts at dawn and four chestnuts at dusk.”

Knowing that there would still be four in the evening, the monkeys were satisfied with this proposal and they nodded their heads in agreement.

This story was mentioned in On the Equality of Things, one of the chapters of the ancient Chinese work Zhuangzi (1) from the Warring States period (475-221 B.C.).

The idiom “three at dawn and four at dusk (朝三暮四, zhāo sān-mù sì)” originated from this story and originally meant to fool others by playing tricks. Later, it was used to mean frequently changing one’s mind or not being responsible.

Today, it is used to describe people who are always changing their minds so that one can never depend on what they say.

An English equivalent might be “to play fast and loose” (as in a con game) or “to blow hot and cold” (capriciously change one’s mind).

Note:

“Zhuāngzǐ (莊子)” is a foundational Daoist text written by Master Zhuang. It contains stories and anecdotes that reflect the carefree nature of a true Daoist sage. The writings in this collection are often of a humorous or irreverent nature.