A philosophical belief was established by the founders of the Zhou Dynasty (周朝) around 1100 B.C. that Heaven bestowed the divine right of ruling to those who were morally worthy.

This belief, known as the “Mandate of Heaven” (天命, pronounced tiān mìng), is rooted deeply in Chinese culture and has had a fundamental and enduring influence on Chinese history.

It established that a ruler must be wise and just, follow the Dao—the Way of Heaven—and be attuned to destiny.

The ancient Chinese regarded the emperor as a “son of Heaven,” with Heaven above him.

Lao Zi (老子) expressed his idea of the unity of Heaven and humans in the Dao De Jing (道德經): “Man follows the Earth, the Earth follows Heaven, Heaven follows the Dao, and the Dao follows what is natural.”

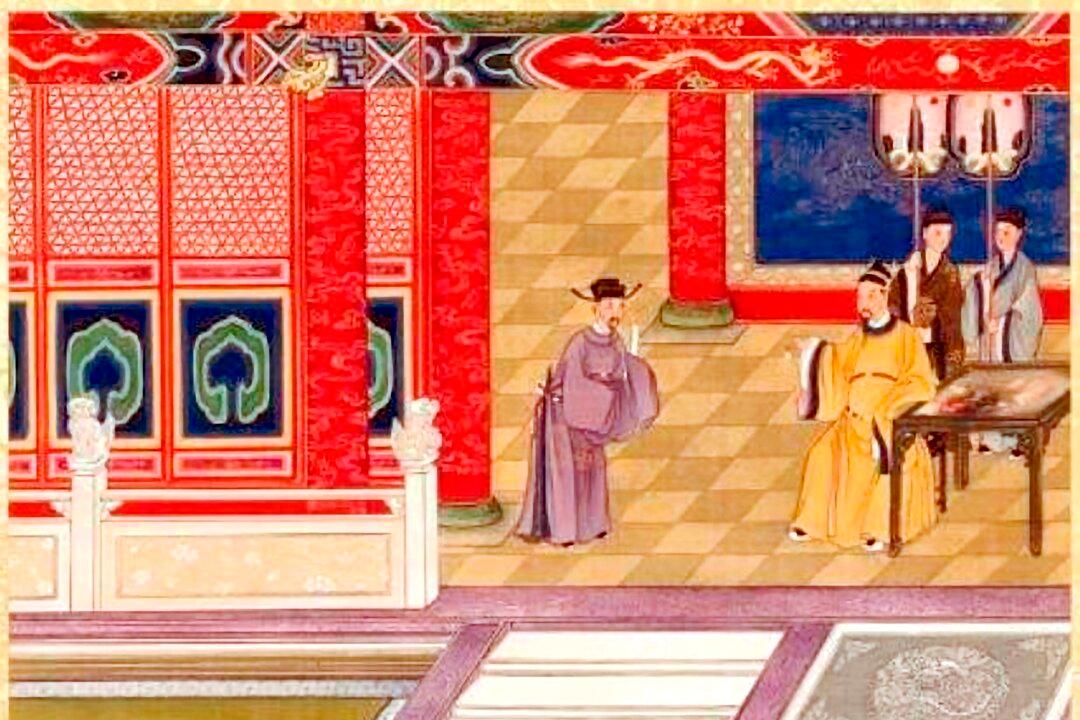

Wise and capable rulers in ancient China revered Heaven and cherished, respected, and protected their subjects. Historians recorded all the words and deeds of the emperor, and the emperor’s behaviour was judged by the Confucian classics.

Sage kings had wise and virtuous officials serve as their teachers or advisers. One example is Yi Yin (伊尹), who helped Shang Tang (商湯) found the Shang Dynasty (商朝) and became its first prime minister.

Jiang Ziya (姜子牙) is another example. He assisted both King Wen (周文王) and King Wu (周武王) in establishing the Zhou Dynasty.

Enforcing the Dao on Behalf of Heaven

If a ruler is immoral, he would be criticized by his ministers and the people, and the people may overthrow him, such as Shang Tang’s defeat of Xia Jie (夏桀), the last emperor of the Xia Dynasty (夏朝), who was a tyrant.

Another example is King Wu’s removal of Emperor Zhou (紂王), the last ruler of the Shang Dynasty.

Traditional Chinese culture did not consider these uprisings as violations of loyalty or the Dao, but rather as enforcing the Dao on behalf of Heaven.