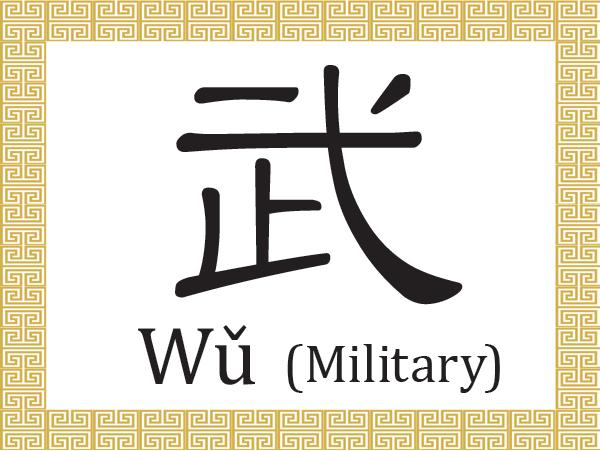

The Chinese character 武 (wǔ) is commonly used as an adjective referring to “military,” “combative,” or “martial,” and also means being warlike or fierce, as well as brave, courageous, valiant, powerful, or formidable.

It is also used as a noun that refers to a footstep, footprint, or trail.

武 (wǔ) is formed by combining the characters 止 (zhǐ) and 戈 (gē). 戈 (gē) is an ancient Chinese halberd or spear, while 止 (zhǐ) means “to stop” and also refers to a foot.

While one interpretation of 武 (wǔ) is that it may have originally referred to a man on foot holding a spear, a definition found in the ancient Chinese historical text “Spring and Autumn Annals” speaks directly to the moral principles associated with martial arts that lie at the heart of traditional Chinese culture.

止戈為武 (zhǐ gē wéi wǔ), literally “stopping the spear constitutes martial arts,” expresses the Chinese concept that genuine martial arts have the ability to stop or prevent warfare or violence.

The phrase later also took on the meaning that true martial arts are capable of compelling the other side to surrender without the use of force.

Chinese martial arts are not only concerned with physical techniques and strategies in fighting, warfare, and self-defence, but also encompass the nurturing of health, fitness, longevity, and one’s capacity for self-healing. Central to these themes is the cultivation of virtue and the manifestation of noble principles that are honoured during combat.

The character 武 (wǔ) is used in many character combinations that refer to martial arts and military action.

Examples include 武術 (wǔ shù) or 武藝 (wǔ yì), martial arts; 武士 (wǔ shì), warrior or knight; 武器 (wǔ qì), weapons; 英武 (yīng wǔ), having a martial look or bearing; 武功 (wǔ gōng), military merit or achievement; 武俠 (wǔ xiá), a martial arts hero or the quality of being knightly or chivalrous; and 武德 (wǔ dé), martial virtue or a chivalrous spirit.

A traditional Chinese concept that is often referred to in relation to 武 (wǔ) is 文 (wén). While 武 refers to military affairs and martial arts, 文 relates to scholarly and cultural pursuits. These two complementary concepts represent the perfect combination of skills and qualities that a human being can have.

The phrase 文武雙全 (wén wǔ shuāng quán) describes someone who is highly capable both as a scholar and a soldier—one who has mastered both the pen and the sword.

Note: The “Spring and Autumn Annals,” or “Chunqui” (春秋), is one of the Five Classics of Confucianism and covers the history of the feudal state of Lu (魯), the home state of Confucius, between the 8th century and 5th century B.C. during the early part of the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (東周) (770–221 B.C.). This period was named the Spring and Autumn Period (770–476 B.C.) due to the prominence gained by the “Spring and Autumn Annals” in Chinese literature.