Meimei was late for school. “How come?” she thought. Her mother always woke her up in the morning. She caught sight of her father. He was late, too. Apparently, her mother hadn’t woken him up either. So where was she?

Then the phone rang.

The 16-year-old girl picked it up. The man on the other end of the line introduced himself as a supervisor at the local police station. “Your mother was arrested for doing Falun Gong exercises in a park. Ask your father to bring 5,000 yuan to the police station tomorrow, or you can figure out the consequences yourself,” she recalls him saying.

Her father, himself a corrections officer, started to call his contacts, desperately trying to find somebody who knew somebody at the police station.

That afternoon, another call came, informing them that her mother was transferred to a police station one level above.

“I was very, very scared,” Meimei said. She knew another Falun Gong practitioner who had recently been beaten to death at that police station.

“We have to save mom,” she implored her father, who was a member of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in good standing.

Her father solicited help from a well-to-do uncle, who promptly started to spread envelopes of cash around and ask questions until he found the right person.

After about four days, the uncle managed to arrange a prison visit. But only Meimei was allowed in.

It was around the Chinese New Year. The police station was cold and dark. She was ushered into a room where she saw a family friend who also practiced Falun Gong. He tried to shy away, but she could see a footprint on his face.

Completing the dreary scene, two policemen sat in a corner, wearing sunglasses and playing chess. Then her mother was led in. Meimei hardly managed to get a sentence out. She spent the rest of the 15 minutes crying.

Once again, the uncle sent cash to various higher-ups in the police department. Finally, after about two weeks, her mother was released.

“Who did this to you?” Meimei shouted as she saw her mother’s body covered in black bruises. She was angry. She wanted to fight. Even if there was no way to do so.

Her mother stopped her. “They are victims, too,” she said, “because they don’t know that what they’re doing is wrong.”

Meimei was shocked. She knew Falun Gong’s tenets—truthfulness, compassion, forbearance—as she had read the practice’s teachings and done the meditative exercises. But this was the first time she really understood them.

“I think at that moment, I realized what compassion is,” she said.

Meimei, which is not her real name, is one of millions of children who grew up in China fearing for their lives and for those of their families after the CCP launched its brutal persecution of Falun Gong 25 years ago.

‘Upside Down’

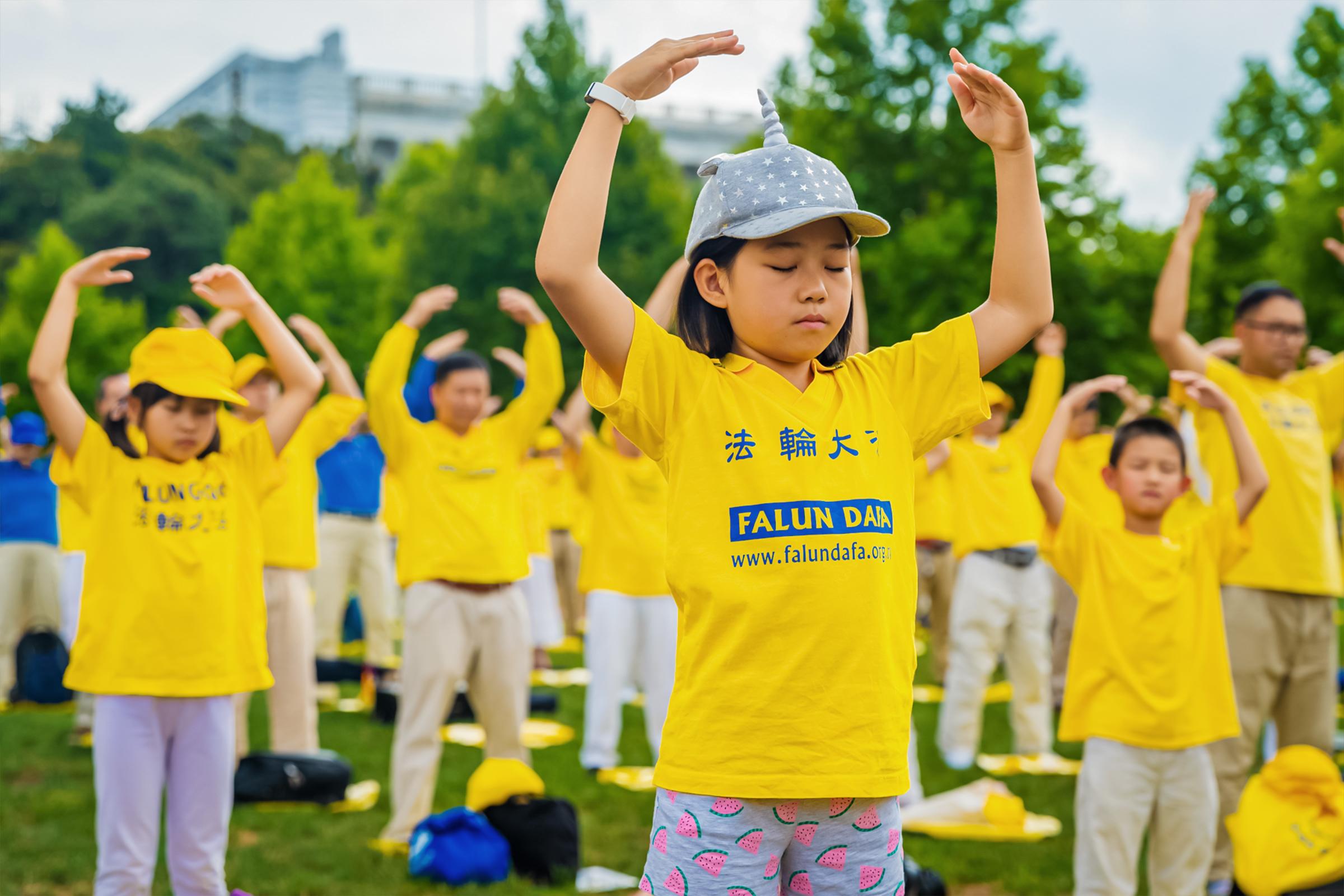

Falun Gong, a practice of slow-moving exercises and moral principles, was passed down from master to disciple in a lineage stretching back to antiquity, similar to the plethora of other Buddhist or Taoist practices that, starting in the 1970s, made their way into broader public under the “qigong” moniker.Qigong practices, which were touted primarily for their physical health benefits, keeping their spiritual underpinnings low key, offered a precious avenue for the Chinese to stay in touch with their culture during the anti-tradition purges of the late Cultural Revolution.

Falun Gong, also known as Falun Dafa, was introduced to the public much later, in 1992, when its founder, Mr. Li Hongzhi, held a series of seminars across the country. With the public already somewhat familiar with qigong, Falun Gong delved deeper into the spiritual aspect; it taught that the key to good health and progress in the practice was in cultivating one’s character in accordance with the principles of truthfulness, compassion, and forbearance.

The practice rapidly spread, primarily by word of mouth. Based on government surveys in the late 1990s, 70 million to 100 million had taken up Falun Gong, and most reported improved physical and mental well-being. Commonly, parents would lead their children to do the exercises and follow the principles as well.

Nearly all who spoke to The Epoch Times had first considered themselves Falun Gong practitioners, and dedicated ones, at the age of 5 to 15.

On July 20, 1999, state media across China denounced Falun Gong, announcing that it had been banned by the CCP. The night before, all over China, Falun Gong assistants—volunteers who brought stereos to play exercise music at outdoor practice sites—were arrested.

To many, especially young practitioners, the news was a complete shock.

“We just felt so strange,” said Livia, who was 11 at the time.

She and her parents regularly went out to practice the Falun Gong exercises with others in the area.

“Many government officials knew us and were quite friendly toward us,” she said.

But all of a sudden, the news was portraying Falun Gong as outright evil.

“My parents and I just couldn’t believe that,” she said.

The media’s tone toward Falun Gong switched from positive to negative virtually overnight, recalled Amy, who was 8 at the time.

It was jarring.

“It was like heaven and earth were turned upside down,” said Yu, who was 13 at the time. What was true just the day before was now supposedly false, and preposterous claims were now presented as unquestionable fact.

There was a widespread feeling among Falun Gong practitioners that there must have been some mistake, and that the situation would be promptly rectified.

“There must be a misunderstanding,“ Phoebe, who was 18 at the time, recalled. ”We had to let them know [the arrested Falun Gong practitioners] are good people. We had to do something.”

Thousands went to local government offices or traveled to Beijing to file appeals or simply tell people on Tiananmen Square that “Falun Dafa is good.”

The Party responded with mass arrests, detention, and torture.

At first, the police appeared confused about what to do, some interviewees said. Those practitioners who went to Beijing were arrested, had their personal information taken down, and then were released within a few days.

That quickly changed.

Local authorities, apparently under pressure from the top, started treating appeals in Beijing as a serious offense punishable by months or even years of detention in a forced labor camp.

Accounts of torture soon followed: beatings that lasted hours, electric shocks with multiple cattle prods until the smell of the victim’s burning flesh filled the room, days-long interrogations and sleep deprivation, force-feeding through the nose with concentrated salt water, the breaking of joints and thrusting of bamboo sticks under fingernails, injections of unknown chemicals, rape, and dozens of other methods honed to inflict maximum pain.

Almost immediately after the launch of the persecution, practitioners started to print and hand out flyers, several interviewees said. At first, the flyers usually focused on local cases of practitioners being wrongfully arrested. Later, they produced more generalized leaflets and brochures debunking the CCP’s propaganda and started delivering them to people’s mailboxes, usually in the dead of night.

Getting caught with such materials could land one in prison or a labor camp for years.

Livia’s parents were sent to labor camps and various detention facilities at least 10 times, she said.

One year, when Livia was in middle school, both her parents and her grandparents were detained at the same time. Other relatives didn’t want to get involved, fearing they would be targeted too, so she remained alone, surviving on school lunches and whatever else she could get.

“It was a very hard time for me,” she said.

But securing food and other basic necessities wasn’t the real problem for her.

Propaganda Machine

In the first months of the persecution, anti-Falun Gong messaging became ubiquitous, saturating all TV channels, radio stations, and newspapers.For anyone familiar with Falun Gong, the propaganda sounded absurd. The practice was accused of leading to murder, suicide, and even terrorism—all antithetical to its teachings, which expressly prohibit killing.

The sheer volume of propaganda, however, ensured that many people accepted at least some of the claims.

One of the most common early smears was that Falun Gong practitioners were cutting open their stomachs to “find Falun.” There’s zero evidence that any such thing ever happened—it appears to be a complete fabrication by the regime—yet many Chinese unquestioningly accepted it as true, multiple interviewees noted.

Denouncing Falun Gong became a mandatory national exercise. People were required to sign anti-Falun Gong petitions, stomp on photos of Falun Gong’s founder, and denounce the practice before entering government offices. Anti-Falun Gong propaganda became part of elementary school textbooks, school exams, and mandatory “political education” classes for schoolchildren in China.

For those who believed the propaganda, Falun Gong practitioners were worse than criminals, Amy said.

For many, it harkened back to the fanaticism of the Cultural Revolution, when people had to recite Mao Zedong quotes even to buy groceries.

Only this time, people were already conditioned into pragmatic cynicism. Many of those who didn’t believe the propaganda nonetheless considered Falun Gong practitioners foolish and irrational for sticking to their faith in defiance of the regime’s slander, Livia said.

“[People thought] my whole family was so stupid. They thought it was just so easy, because you could just give up Falun Gong. Why do you have to insist on that?”

Faith held no meaning for them, she said.

Amy remembered a political education class during which she tried to speak up. “Falun Gong isn’t like that,” she said as the teacher was unloading a barrage of propaganda. The teacher shut her down immediately. “What’s your evidence?” she shouted at Amy in the hallway after class.

The payback came swiftly. The next day, Amy was treated to a whole-class shunning in which the other children called her names she didn’t want to repeat.

A few of her friends stuck by her, but later told her that teachers instructed them to stop talking to her lest their education be “affected.” She was heartened to hear that they were willing to defy the teachers’ orders and remain friends with her. Still, she didn’t want them to get into trouble. She suggested they should only show their friendship in private. Over time, they got pulled ever further apart, until she was alone.

Her father, who didn’t practice Falun Gong, insisted she stay in school, and so she kept going, facing constant snubbing and denigration.

Collective Guilt

Ben was 17 when the persecution began.“I couldn’t understand,” he said. “I didn’t know what had happened.”

Friends and family streamed to his home, trying to persuade him and his father to stop practicing or at least keep it a secret. Remembering the Cultural Revolution, they feared that if one person was labeled an enemy of the Party, the whole family would be targeted.

“You cannot practice this anymore because your cousins, they go to high school and college in a few years. They will be persecuted,” he was told by his uncles.

The CCP’s use of collective guilt, or guilt by association—in which one’s supposed political transgressions bring punishment to one’s family, friends, colleagues, and even workplace or school—has been mentioned by multiple practitioners as a source of psychological torture.

It’s one thing to resist orders from the government to renounce one’s faith, but it’s quite another to resist impassioned pleas from genuinely concerned relatives and friends.

In 2000, Ben’s father went to Beijing to appeal to the regime and was arrested. Over the next decade, Ben saw him for a total of only a few months. His father would be released only to be arrested again and sent to another detention center or labor camp.

Ben had to give up on college. To support himself after high school, he went to work as a waiter in a restaurant and later in various fast-food outlets such as McDonald’s and Burger King.

Nobody would dare help him. Even his manager at work was repeatedly harassed by police.

“I had pressure from my boss, from my family, from my classmates and friends,“ he said. ”So I started having mental health problems. I stopped talking to people, for a very long period of time.”

He suffered from depression, intense feelings of fear, and hopelessness.

When his father was released in 2009 after a two-year stint in a labor camp, he encouraged Ben in his faith, and gradually Ben’s mental state improved. He joined a career development program and learned to code.

It was clear that his father had been tortured, but when he asked him about it, he didn’t want to talk.

“I asked him a few times. He said, ‘No, I don’t want to say. It’s too terrible. I don’t want to recall those memories,’” he said.

He did mention beatings, though, as well as the “tiger bench”—being forced to sit on a tiny stool for days, which causes excruciating pain and extensive injuries to one’s buttocks.

True Character Revealed

In 2001, Yu lived in a high school dormitory—10 girls squeezed into one room filled with bunk beds. She hid some Falun Gong materials under her mattress, not realizing that they would be visible through the bed planks to her bunkmate below.“Yu, could you remove it? Every time I look up, I see it. It makes me very uncomfortable,” the girl below, a childhood friend, told her.

Several other roommates overheard the comment. Yu wanted to explain. “Don’t believe what the government says,” she said. She started to talk about her mother’s friend, who repeatedly went to appeal in Beijing and was arrested and eventually sentenced to 12 years in prison. As she spoke, tears started to roll down her cheeks.

She was met with utter apathy. One of the roommates even started to laugh. “Why are you crying? It’s not your family,” the girl said.

Yu never tried to talk to her classmates about the persecution again. She would also seldom smile.

Four years later, in medical school, Yu grabbed another opportunity—an English class teacher, an American, gave the topic of “hero” as a speaking assignment.

When Yu’s turn came, she stood up and started to talk about her imprisoned family friend.

“I said she was a hero in my heart because she stood up for her righteous faith,” Yu said.

The class went silent. The teacher didn’t say anything. Eventually, the class Communist Youth League representative stood up and rattled off some propaganda.

After the class, Yu felt uneasy. She thought she did the right thing but wasn’t sure what would happen. She was hopeful her close friends would support her, but now they wouldn’t even talk to her.

On her way back to the dorm, she felt hurt and lonely. When she opened the door, only one girl was in the room—the dorm’s student representative. Yu didn’t very much enjoy her company, considering her rude, spoiled, and inconsiderate, as she often stayed up late when others wanted to sleep.

To her surprise, this girl started to shout, “Yu, if you get arrested because of this, I’ll go rescue you!”

Yu’s heart melted. She found herself smiling.

The ‘Three Withdrawals’

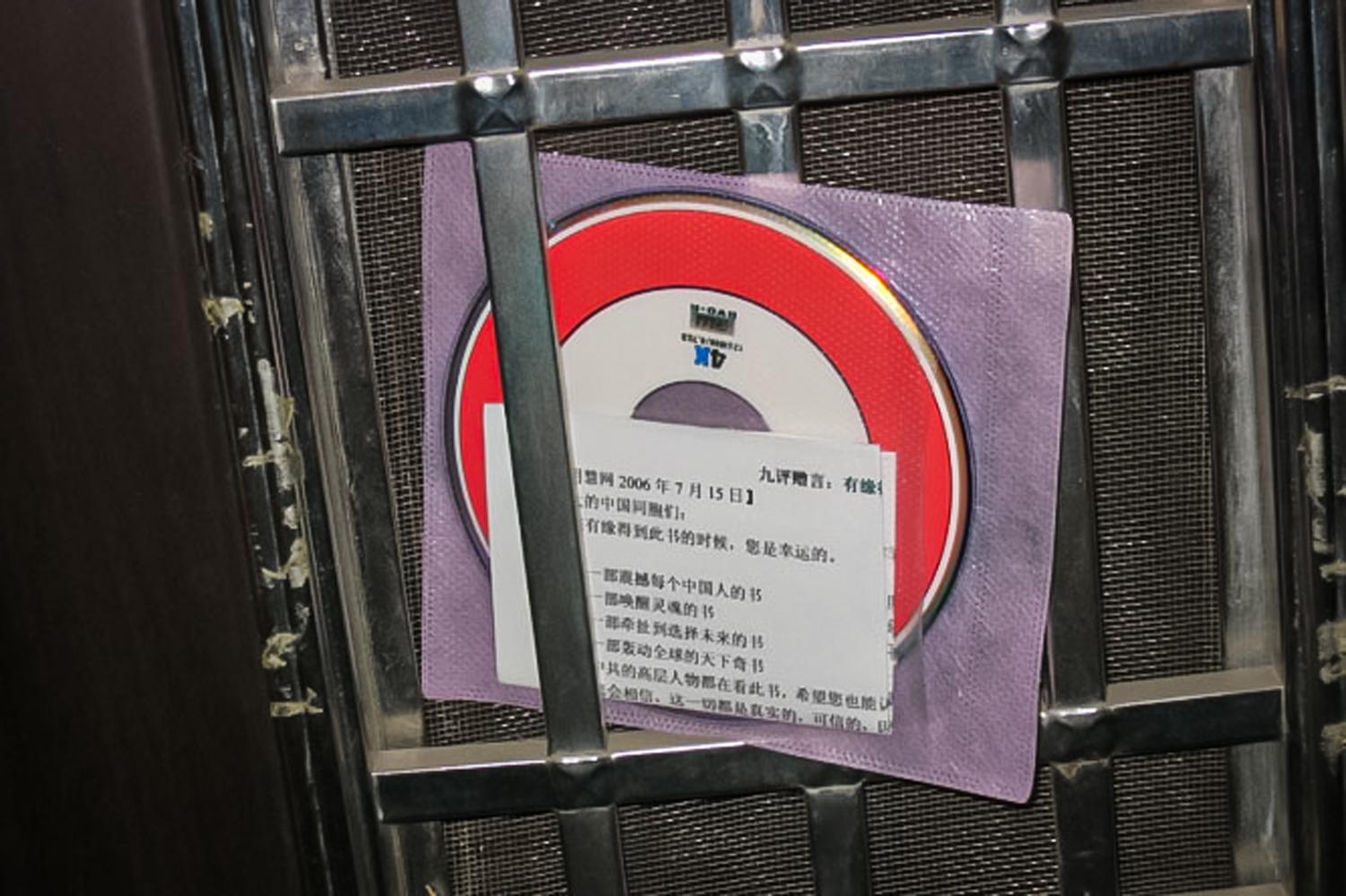

When the persecution first began, many practitioners held out hope that perhaps if they explained themselves better, the Party would change its stance. Year after year, they believed that the persecution was about to end, Yu said.In November 2004, a major shift came with the publication of the “Nine Commentaries on the Communist Party,” a series of editorials published by The Epoch Times. Its detailed and sobering analysis of the CCP’s history, atrocities, and methods dashed any remaining hope that the Party would change.

As the editorials document, labeling a segment of society as an enemy marked for eradication has been a core tactic used by the Party to hold onto power.

“I was fundamentally shocked,” Livia said of the first time she read the “Nine Commentaries.” Finally, it made sense to her why the CCP was persecuting innocent people who, by any reasonable account, were of no threat.

From that point on, the general sentiment among Falun Gong practitioners was that the persecution would only come to an end with the end of the CCP.

“Before that, we tried to convince the leaders of China to accept Falun Gong. We tried to use our compassion, kindness, try to transform their thoughts, petition and write letters, clarify the truth,” Sam said.

“After the ‘Nine Commentaries,’ I realized we were not going [to succeed via] that route anymore. ... There’s no hope that they will change, [that] they will stop the persecution.”

The “Nine Commentaries” sparked a movement called San Tui, or the Three Withdrawals, which refers to quitting the CCP, the Communist Youth League, and the Communist Young Pioneers. While the Party only has about 100 million members, almost every Chinese person at some point has joined one of its affiliates.

Rather than formally canceling such a membership, San Tui means making a statement to internally separate oneself from the Party and its crimes.

Many practitioners noticed that spreading the “Nine Commentaries” changed attitudes toward Falun Gong.

Even people thoroughly convinced by the CCP’s propaganda were flabbergasted after reading the editorial series, Amy said.

“Even those very stubborn people brainwashed by the CCP, they couldn’t argue back,” she said.

The “Nine Commentaries” provided clarity for people who had long been taught that there would be no China without the CCP, said those who spoke to The Epoch Times.

“In China, people really had a hard time differentiating between the Chinese Communist Party and the Chinese people,” said Mike, who was 8 when the persecution started.

Killing for Organs

In 2006, The Epoch Times broke the story on the CCP’s killing of Falun Gong practitioners to harvest their organs for use in the lucrative transplant industry. The allegations first came from several whistleblowers, and the evidence quickly snowballed.After 2000, China’s minuscule organ transplant system suddenly exploded. The supply of organs was so staggering that many hospitals were opening new transplant wards, and even whole hospitals dedicated to transplants began springing up around the country.

Some hospitals were openly boasting of completing hundreds of transplants a year compared to just a handful a few years prior. Yet the country had virtually no organ donation system. Even with China’s admitted use of death-row prisoners as an organ source, those numbers wouldn’t have been possible. There was no indication that China was suddenly sentencing to death exponentially more people.

Most notably, hospitals were advertising wait times of just one or two weeks—organs were waiting for patients, not the other way around.

Undercover investigators called hospitals, pretending to be patients in need of an organ transplant and asking specifically for organs from “Falun Gong.” They were met with reassurances that those were indeed available.

The news was both frightening and sickening, several interviewees said.

“I couldn’t eat food for several days,” Ben said. “I could not believe such a thing had been happening for years.”

For Meimei, who was away from home at a boarding school at the time, it was a constant source of anxiety.

“I was very scared and worried about my mom, especially every time she didn’t answer her phone,” she said.

“It was a big shock for me,” recalled Phoebe, who was just finishing high school in Dalian, the second-largest city in Liaoning Province, when the persecution began.

Her father was a lawyer and her mother was a local prosecutor, providing her a comfortable life insulated from the suffering of ordinary Chinese by fluff propaganda.

“For me, the government was always pictured as really nice,” she said.

When the CCP turned on Falun Gong, which Phoebe had practiced with her mother since 1995, she thought it must have been a bad joke.

“I had no concept that the government could do this to people,” she said.

“You can’t even think what you want to think? You can’t even believe in what is good? ... That was the first time I clearly saw how evil the Party was.”

Due to her mother’s prominent position and work record, nobody dared to go after her at first—until she decided to write a letter defending Falun Gong and sent it to every judicial and law enforcement official in China she could think of.

In December 1999, she traveled with Phoebe to Beijing to appeal. At a security checkpoint on Tiananmen Square, police found the letter and a Falun Gong book on them. They were arrested on the spot and detained for several days.

After that, her mother was put under surveillance and forced into early retirement. Police periodically ransacked their home and detained her mother again and again, before she was eventually sentenced to three years in the notorious Masanjia Labor Camp. She was released after one year to undergo eye surgery—a lucky break Phoebe credited to the camp’s hesitancy to abuse a former prosecutor too harshly.

When the family learned the news about the killings of practitioners for their organs in 2006, they were disturbed to realize their province appeared to be heavily implicated.

“This really made me sick,” Phoebe said. “I was determined to expose the evil if I got a chance to come overseas.”

However, her passport application had been denied a few years earlier. She had apparently been blacklisted.

Nevertheless, she reapplied and, in a stroke of fortune that she credited to the divine, the government’s file on her had been corrupted after a switch to a new system of issuing passports.

Because all her personal information in the system was wrong, she was asked to get an approval letter from her local police station. Stunningly, her locality was reassigned to a different police station where nobody knew her. She was issued the letter and subsequently her passport, allowing her to come to the United States in 2006.

Parents Gone

For Flora, who was born in 2000, the persecution was an ever-present part of life. At the time of her birth, her father was already in a labor camp for appealing for Falun Gong in Beijing in 1999. He was released when she was 2.Since as far back as she could remember, she had heard about people being arrested for practicing Falun Gong. When she went to school, her grandparents exhorted her not to mention her faith. Her mother always used old cell phones with removable batteries, to minimize surveillance. Their apartment had a second, hidden doorbell only revealed to trusted people.

“I felt like I was born into a prison,” she said. She had to always watch what she said and to whom.

In 2007, both her parents were arrested during the purges ahead of the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

She was doing her homework while her mother was cooking dinner, she remembered, when somebody banged on the front door. Her mother opened the door and about 10 people rushed in. She recognized them as police as well as an official from the university where her mother lectured until her career was cut off because of her appeal in Beijing in 1999.

The police didn’t even have handcuffs, instead tying her mother’s hands with a belt, she said. They ransacked their home, videotaping and confiscating any Falun Gong materials they could find. They also stole cash and the family’s TV. Meanwhile, a female officer was trying to distract Flora, asking her about her homework as if the frightened girl couldn’t plainly see what was happening.

“I didn’t cry, because I was in shock. But I remember my legs were shaking so much,” she said.

The police loaded her in a car to drop her off at her grandmother’s place in the same city.

During the ride, she asked why her mother had been arrested.

“It was like they didn’t know what to say,” she said.

Then one person answered: “Your mother was arrested because she practices Falun Gong.”

“That shouldn’t be why you arrest people,” she remembered answering.

The rest of the ride was silent.

Her father, she later learned, had already been arrested at the small shop he ran. He was locked up for 19 months. Her mother was released after four months.

Then, one day in 2012, Flora came home from school during her lunch break to find her parents gone again. Her aunt was there, trying to lie to her about what happened. But it was pointless. She knew right away.

The police had come when both her parents were at home, she later learned. They nabbed her mother as she answered the door. But her father managed to lock a secondary door. He then climbed out the fourth-floor window and across an air conditioning unit to the window next door. By a stroke of good fortune, it was open. He climbed in.

Luckily, the neighbor didn’t report him. After some time, he slipped out and disappeared. He never came back home again. In 2014, he fled overseas.

Shortly after finishing high school, Flora came to the United States to study. After college, she joined NTD Television, a sister media outlet of The Epoch Times.

It was her experience with the persecution that motivated her to get into media work, she said.

Surveillance State

With the incessant efforts to counter the state’s propaganda, many practitioners have noticed a gradual shift in public attitude. Ignorance and hostility have begun to slowly dissipate, replaced by sympathy, though indifference remains common.Livia once managed to explain the facts about Falun Gong to several classmates at her high school. When their politics teacher brought up Falun Gong propaganda one day, the classmates started to speak up. She quickly joined in, sharing her understanding with the whole class.

“The teacher was shocked,” she said. “And she just said that this topic is forbidden to talk about in the classroom.”

She said the teacher argued that “because we were ruled by the CCP, when we are against the CCP, it is our fault.”

In the early years, trying to talk about Falun Gong to a stranger posed a major risk of getting reported to the police.

Mia, who was 6 when the persecution started, remembered the terror she felt when her father brought up Falun Gong with somebody they’d met, such as a taxi driver.

“I just had this great fear in my heart, and I didn’t dare to listen,” she said. “I was afraid of their response.”

Today, it seems that hardly anybody would bother reporting a Falun Gong practitioner, some interviewees said.

Recently, after experiencing the draconian COVID-19 lockdowns, many Chinese have woken up to the nature of the CCP, Mike said.

One of his classmates reached out to him, saying: “Back in the day when you were telling us to quit the Chinese Communist Party, we were all thinking you were crazy. But now, after COVID happened, a lot of people died, they locked us at home, I know what you were talking about.”

However, while the environment may have relaxed in one way, it has stiffened in others.

Crude means of electronic surveillance have grown increasingly sophisticated over the past quarter-century. The prying eyes of brainwashed neighbors have been replaced by zooming camera lenses and untiring facial recognition algorithms.

Falun Gong practitioners have grown accustomed to seeing cell phones as spies and street cameras as cops. These days, Falun Gong-related activities are never discussed electronically, Mike said.

He and others described various ways used to hide and disguise their activities. The Epoch Times decided against revealing them, as some may still be in use today.

Many affirmed, though, that such a lifestyle takes a psychological toll. Even after coming to the United States, they struggle with deep-seated fear, their hearts racing when somebody unexpectedly knocks on their door or when they see a police car approaching.

“I wasn’t arrested or put in a labor camp or prison or jail,” Sam said, “but the persecution really harms everyone, especially young children and teenagers.”