I had the pleasure of speaking at Pace University’s recent Threat Intelligence Forum about what’s really behind Chinese cyberespionage, and I thought it would be useful to replicate that talk here.

There are enough Chinese cyberattacks where it’s fair to say most of us are familiar with the surface picture. There were close to 700 Chinese cyberattacks designed to steal corporate or military secrets in the United States between 2009 and 2014, according to an NSA map released by NBC News.

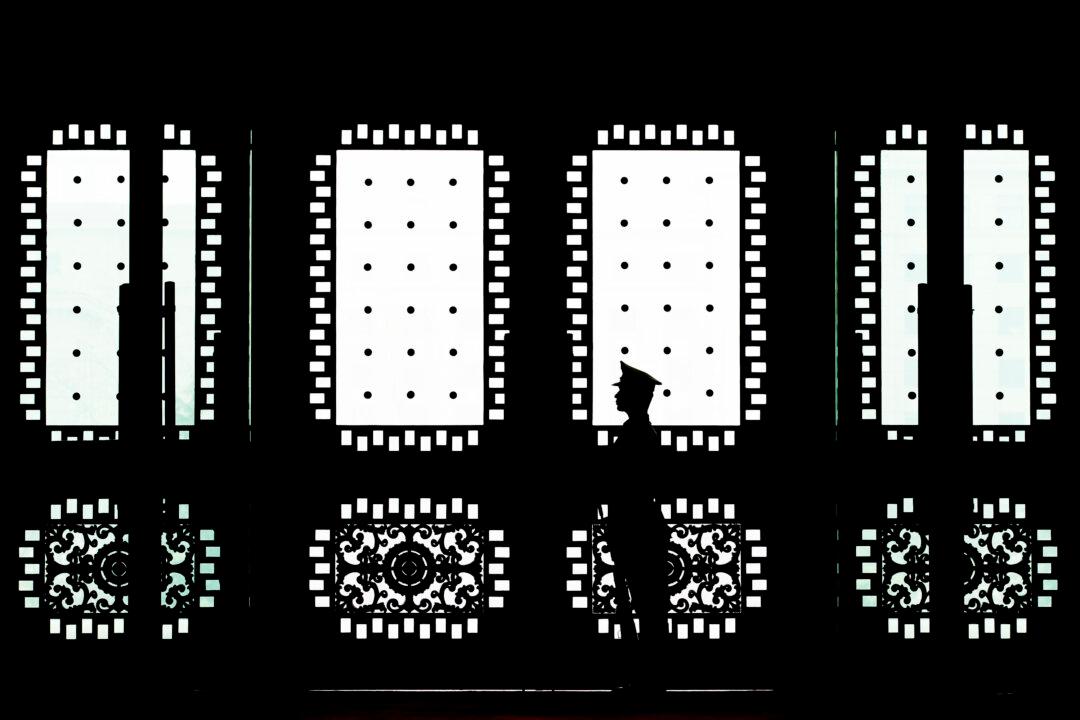

It’s also important to note the attacks designed for economic theft are only a small piece of the larger picture. Many Chinese cyberattacks are designed to spy on dissidents living abroad, keep tabs on foreign news outlets, spy on governments, or to censor individuals and organizations that are critical of the Chinese regime.

In March, for example, it launched cyberattacks on the anti-censorship website GreatFire.org. In June, it stole 21.5 million background checks from the U.S. Office of Personnel Management on current and former federal employees. In September, the Chinese regime was caught spying on the U.S. government and European news outlets.

The attacks designed for economic theft usually get the most attention—and with good reason. Retired federal prosecutor David Loche Hall explained the economic seriousness of these attacks in his recent book, “Crack99.”

There are 75 industries in the United States identified as intellectual property (IP) intensive, according to Hall. These industries hold 27.1 million American jobs, or 18.8 percent of all employment. Each of these jobs also supports one additional job through the supply chain.

So, when you look at the whole picture, close to 40 million jobs, or 27.7 percent of all employment in the United States, relies on protection of IP. And it’s this IP that the Chinese regime has been stealing with cyberattacks.

Close to $300 billion and 1.2 million American jobs are lost each year to IP theft, according to the Commission on the Theft of Intellectual Property.

“When this innovation is meant to drive revenue, profit, and jobs for at least 10 years, we are losing the equivalent of $5 trillion out of the U.S. economy every year to economic espionage,” said Casey Fleming, CEO of BLACKOPS Partners Corporation, in a previous interview with Epoch Times.