China has long been known for churning out athletes for the Olympics and international sporting events, including hurdles gold medalist Liu Xiang, three-time world vault champion and gold medalist Cheng Fei, badminton gold medalist Lin Dan, and many, many others.

Other countries might be envious of China’s athletes, but perhaps the number of sacrifices they made to earn the gold medals may not be worth those singular moments of glory.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has established a demanding sports training system that includes numerous state-run athletic schools all over the country. Children with the qualities suitable for sports training are carefully selected and enrolled in these schools.

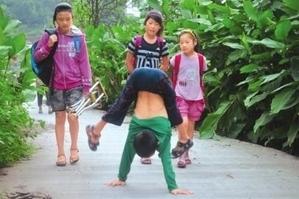

These children—some as young as 4 years old—are trained many hours a day in their respective sports, often while living away from their families.

The children who show exceptional talent are further selected for the provincial team, and the best of them advance to the national team, where they participate in world championships and later, the Olympics, where they are expected to bring home gold medals.

However, victory isn’t all that it’s hyped up to be.

Deprived

Instructed to focus on nothing except sports, many Chinese athletes are deprived from a young age of their childhood, education, and family life. According to a report by Time magazine in 2008, 15-year-old runner Wang Ting, when asked what she does in her spare time, replied, “I run, and I sleep ... That’s my day.”

The Time report also recounted an interview with 15-year-old female athlete Chen Yun, who trains in weightlifting at the Weifang City Sports School in Shandong Province.

When Chen was asked about her favorite sports and hobbies, she answered: “Weight-lifting. When asked if she likes anything besides lifting weights she again replied: ”Weight-lifting” and looked nervously at two men standing near her, according to the Time report.

“Once, I liked to run in the fields near my village,” she began softly, prompting a propaganda official to step in. “But now, she prefers weight-lifting,” he finished for her. “Her goal is to become a star athlete and make China proud.”

Appearing visibly nervous, she said, “I prefer weight-lifting now. I want to become a star athlete and make China proud.”

Wu Minxia, a four-time gold medalist in the 3-meter women’s synchronized springboard, only recently learned that her mother had undergone eight years of breast cancer treatment and that her grandparents had died over a year ago. Her parents had kept the news from her until after she competed in the London Olympics so that she could concentrate on training.

Yahoo Sports last week quoted Wu’s father as saying that Wu’s success has come at the expense of her family life. “We accepted a long time ago that she doesn’t belong entirely to us,” he said. “I don’t even dare to think about things like enjoying family happiness.”

Discarded

Without education or job training, many retired athletes have found it nearly impossible to make a living after sports. Time magazine quoted Xinhua, China’s state-run mouthpiece, and the China Sports Daily publication as saying that nearly half of the 6,000 retiring athletes retiring each year become unemployed. Nearly 80 percent of China’s 300,000 retired athletes are jobless, in poverty, injured, or even crippled from over exercise.

Even for world champions and gold medalists, life after sports is a struggle for survival. Ai Dongmei, the 1999 Beijing International Marathon champion, had to sell her medals in order to feed her family. Cai Li, a weightlifting champion, could not afford medical treatment and died of pneumonia at the early age of 33, the Time magazine report said.

Next ... The Party’s Interests

Former national female weightlifting champion Zou Chunlan was forced to do menial labor for several years and then worked at a public bathhouse as a masseuse.

Zhang Shangwu, a gold medal-winning gymnast at the 2001 World University Games in Beijing was also left destitute after his athletic career abruptly ended. After an Achilles’ tendon injury in 2002, he retired from the sport in 2005 with a pension barely enough to cover his living costs.

Zhang was also forced to sell off two of his gold medals for a grand sum of less than $20, reported ABC News in 2011. In 2007, Zhang was sentenced to four years in prison for stealing laptops and cell phones at a Beijing sports school. After his release in April 2011, Zhang resorted to begging and performing stunts on the streets for money to care for his sickly grandfather.

Retired basketball player Huang Chengyi’s tragic fate has also aroused attention. Huang, who is 7 feet 1 inches tall and once challenged former Houston Rockets center Yao Ming in China’s national training camp, is now paralyzed. He lives in an abandoned hut on a construction site and is completely dependent on his trash collector mother, according to the Asia Health Care Blog.

The Party’s Interests

The Chinese regime has faced widespread criticism about its sports system for indoctrinating athletes with its single-minded pursuit of Olympic gold medals, while depriving athletes of their personal life and education and providing them no means of living after their retirement from sports.

Huang Jianxiang, one of China’s best known sports commentators, told NTD Television: “I oppose this warped gold medal production line, this system that deprives people of their basic rights. Only the gold medalists benefit; all the others are the cannon fodder of the system, worse off than the hundreds of millions of people who were deprived of their sporting rights.”

According to Epoch Times commentator Xia Xiaoqiang, the athletes exist for the system.

“Under this kind of cruel system, these talented athletes have practically enslaved themselves to the state-owned organization,” Xia wrote. “They must give thanks to the Party and the country.”

Chen Kai, a former national Chinese basketball team player told Sound of Hope Radio, “In China, sports are used to meet the needs of power. It is a tool to glorify the CCP. It is not the true choice of an individual athlete. Therefore, sports in China are distorted.”

Meanwhile, netizens on the Chinese microblogging platform Sina Weibo have started a movement called, “Even if you are not a gold medalist, you are still a hero,” urging everyone to treat athletes equally and to stop pressuring them to win gold medals.

The Epoch Times publishes in 35 countries and in 19 languages. Subscribe to our e-newsletter.