The falling yuan and slowing economy must be wearing on the Chinese regime. Otherwise, why would it publish a childish op-ed attacking billionaire investor George Soros—titled “Declaring War on China’s Currency? Ha Ha.”—on the front page of People’s Daily?

First of all, nobody knows whether Soros is really declaring war on the yuan. He only said, during an interview at the World Economic Forum in Davos on Jan. 21, that he was sure Asian currencies and China would have a hard landing.

Maybe it was this statement that rubbed the Communist Party mouthpiece the wrong way, as it also defended the Chinese economy at large, after making this statement about the currency, “Soros’s challenge for the renminbi and the Hong Kong dollar is unlikely to succeed—there is no doubt.”

Aside from the fact that there is doubt if it is just unlikely and not impossible, Soros never said he was targeting the renminbi and the Hong Kong dollar and even granted China the ability to manage a hard landing.

This did not prevent the People’s Daily from blaming him for the steady decline of the yuan. “Because of his influence, fluctuations in the international financial markets have intensified already existing speculative attacks. Asian currencies obviously feel greater pressure.”

So if we assume Soros is indeed shorting the onshore or offshore yuan or the Hong Kong dollar, who would be right, the People’s Daily or Soros?

Maybe the Chinese regime thought it had to nip Soros’s influence in the bud because he is usually right about when currencies have to devalue, especially when they are pegged to other currencies.

For starters, he made 1 billion pounds betting against the Bank of England on Sept. 16, 1992, when Britain had to withdraw the pound sterling from the rigid European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM). Estimates vary, but the Bank of England spent 2 billion an hour on the morning of that day to defend the currency against Soros. Incidentally, this number is close to the $3.5 billion China spent every day in December to defend its exchange rate. At least the Brits gave up in the afternoon. China is still fighting.

Several officials and politicians have also accused Soros of participating in the demise of Asian currencies during the Asian financial crisis in 1997, although it is unclear to what degree and how much money he made.

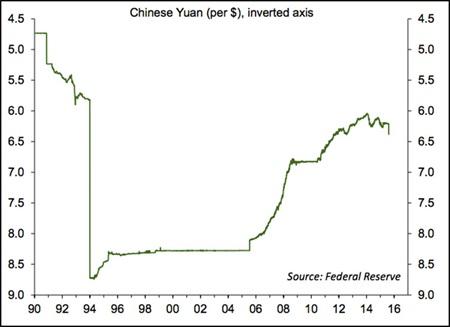

The People’s Daily doesn’t think this matters much though and says we should look at the larger historical context: “The continued appreciation of one currency against the U.S. dollar for such a long time, and with an amplitude so large is rare. A slight pullback now is normal.”

Of course, it helps if the currency devalues 33 percent before it starts to appreciate, like in 1994, which took the rate from 4.7 yuan per dollar to 8.7, but this is beside the point. The point is Soros sees the same problems he saw in Europe in the early ‘90s and in Asia in the late ’90s.