The red picket signs and the fists in the air are gone from Chicago’s streets. Students have been back in school since Sept. 19 and will have to spend some holiday time in school to make up for missed days due to the early-September strike by the Chicago Teachers Union (CTU). Life goes on. Some parents questioned the strike methods.

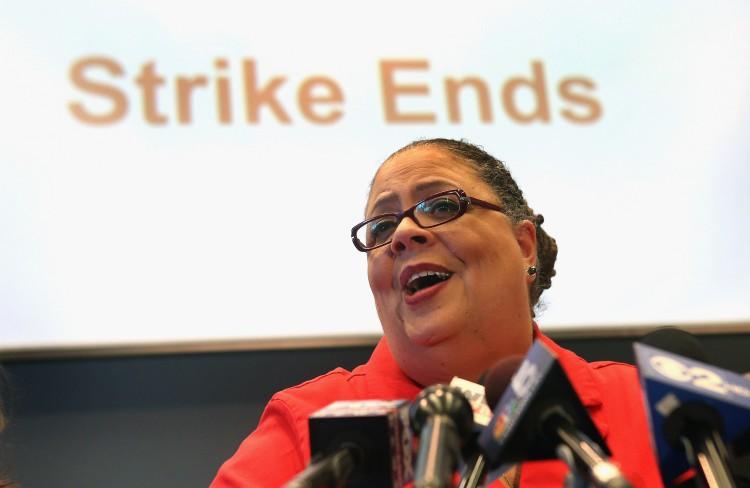

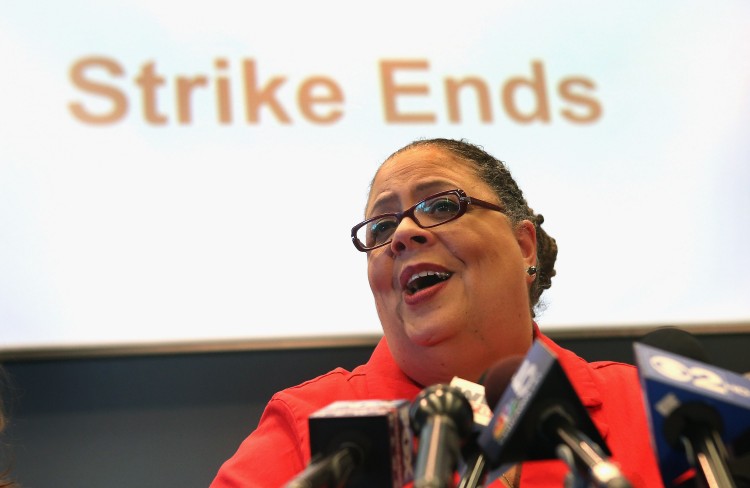

Meanwhile, on Oct. 2 the CTU voted 16,428 to 4,337 to accept the new contract with Chicago Public Schools, which means the strike is officially over.

The contract is good for three years.

“Being the third-largest school district in the nation, it has gotten a lot of news and I’m sure it’s going to make a lot of people think about what they should do in the future,” said Bruce Bohren, president of the Illinois Parent Teacher Association (PTA) in a phone interview.

Chicago has 40,678 employees in Chicago public schools. Though the CTU has an estimated 30,000 members—retirees are members as well—it’s not just the number of union members that play a role in the outcome of a strike.

Looking back, striking is almost like a sports game. It’s all about the fans. Reactions to the strike were mixed, and each team continues to present an agenda to garner public support as education reform continues beyond the strike.

Public servants, like teachers, firefighters, and nurses, are not really dealing with a product. Dr. Victor Catano, professor of industrial organizational psychology at Saint Mary’s University, said in a phone interview that when they go on strike it’s the third parties, or “people like the civilians,” who get stuck in the middle, experience the most stress, and play the most important role.

Rebecca Labowitz, a Chicago parent and blogger on education in Chicago, wrote on CNN that she was sensing an “uptick of anger,” with parents inconvenienced by the strike, schooling put on hold, and uncertainty about what the situation will be day-to-day.