An Ottawa woman who was the victim of marriage fraud welcomes the Canadian government’s latest proposal to crack down on marriages of convenience, but questions whether the money and manpower are there to implement it.

Under the proposed change, now open for public input, foreign spouses being sponsored by Canadians would be required to live with their sponsor in a legitimate relationship for at least two years after receipt of their permanent resident status.

If violated, the sponsored spouse’s status could be revoked, possibly leading to their removal and in some instances, criminal charges could also be laid.

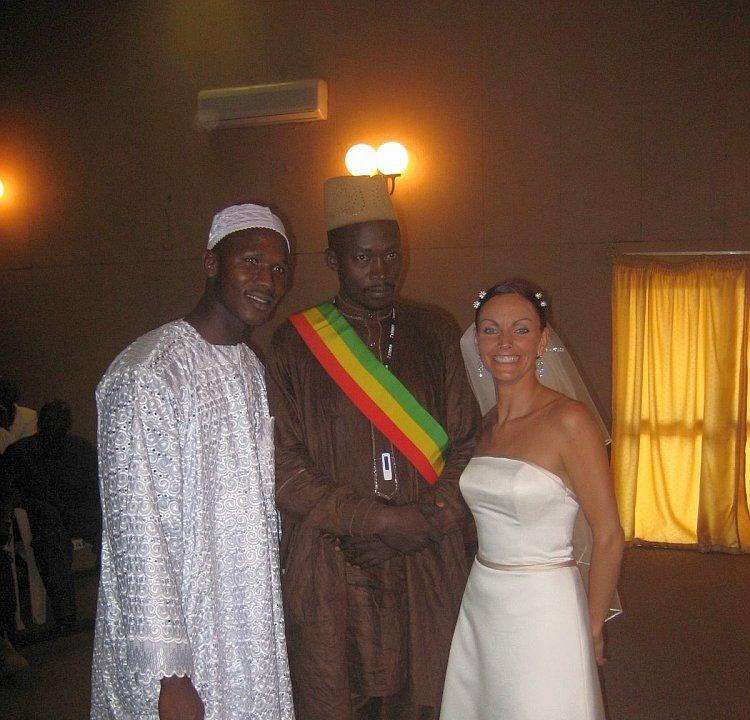

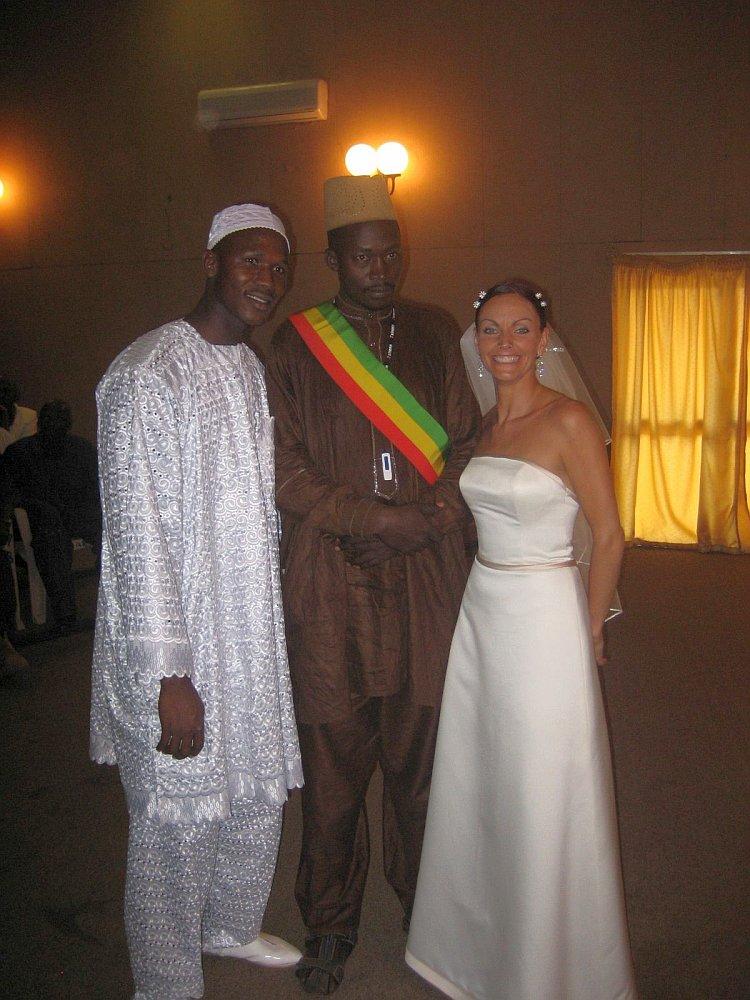

“I’m definitely impressed,” said Lainie Towell, whose West African-born husband deserted her in 2008 three weeks after arriving in Canada.

“Jason Kenney has been a very proactive minister. My hat goes off to him for sure.”

After her heartbreaking experience, Towell, a performance artist, embarked on a campaign to draw attention to marriage fraud, including staging an elaborate protest on Parliament Hill and walking past the Citizenship and Immigration and Canada Border Services Agency offices in her wedding gown with a red door strapped to her back.

In announcing the new measure on March 9, Kenney said the objective is “to weed out people trying to use a phony marriage as a quick and easy route to Canada.”

“In town hall meetings I held in 2010 with victims of marriage fraud, I heard first-hand from victims who were still suffering the consequences years later. They implored me to do something to stop this from happening to others.”

The proposal follows further measures announced on March 2 that require those sponsored to wait at least five years from the day they are granted permanent residence status before they can sponsor a new partner.

The move aims to prevent people from marrying Canadians to gain residency, only to leave them and sponsor a new partner while their Canadian spouse remains financially responsible for them for three years.

Adequate Resources?

Towell says that although the new measures are a step in the right direction, the funds and staff allocated to them will ultimately determine their success.

“One of the issues has always been that … people would call the department about their cases and nothing would be done about it,” she said.

“So the laws are great but my only question is what happens if you have an influx of people calling and saying ‘My spouse has disappeared.’ Do we have the manpower to actually follow through?”

“It would be interesting to know what type of money is put into this.”

The New Democratic Party member responsible for immigration Don Davies has said it would be better to focus on preventing marriage fraudsters from coming to Canada in the first place rather than using resources to penalize them after they’ve arrived.

Others have raised concerns the new regulations could penalize immigrants who are in genuine relationships that happen to end shortly after their arrival in Canada.

Towell, whose ex-husband was finally deported in February after he had exhausted all avenues of appeal, said she feels her efforts may have contributed to tighter laws around marriage fraud.

“When I went public with my story, other people went public and more and more people started telling their stories, and this became more of a mainstream issue. And the number of cases that were opened between 2008 and 2010 while my case was very hot in the media was very high,” she said.

“I’m not saying it’s me alone, but I think that I was able to get the right people to listen who maybe were too busy who weren’t paying attention to this issue.”

Canada allows around 40,000 spouses or common-law partners to be sponsored each year, and some immigration lawyers have estimated “thousands” of sponsors are victims of marriage fraud.

Activist group StopMarriageFraud.ca says marriage fraud occurs in Canada “on a fairly regular basis” and happens to people of all walks of life, both male and female.