The question over the ownership of outer space—all the other planets, asteroids, and stars—has a colorful history. By dent of its inaccessibility, outer space has been fertile ground for contradictory claims of ownership.

A Canadian man once filed dozens of lawsuits in the 2000s staking his claim over different planets in the solar system and four of Jupiter’s moons. In the 18th century, Frederick the Great of Prussia once bequeathed the moon to a physician to compensate for the latter’s services.

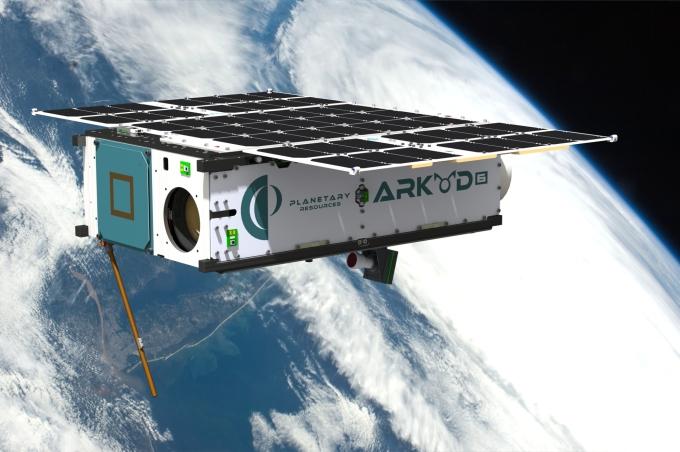

In the past, there was no need to resolve the question of space ownership because of its practical irrelevance to humanity, but that’s about to change. Earlier this month, a mining prospector spacecraft was launched from the International Space Station to test its control systems and software in orbit.