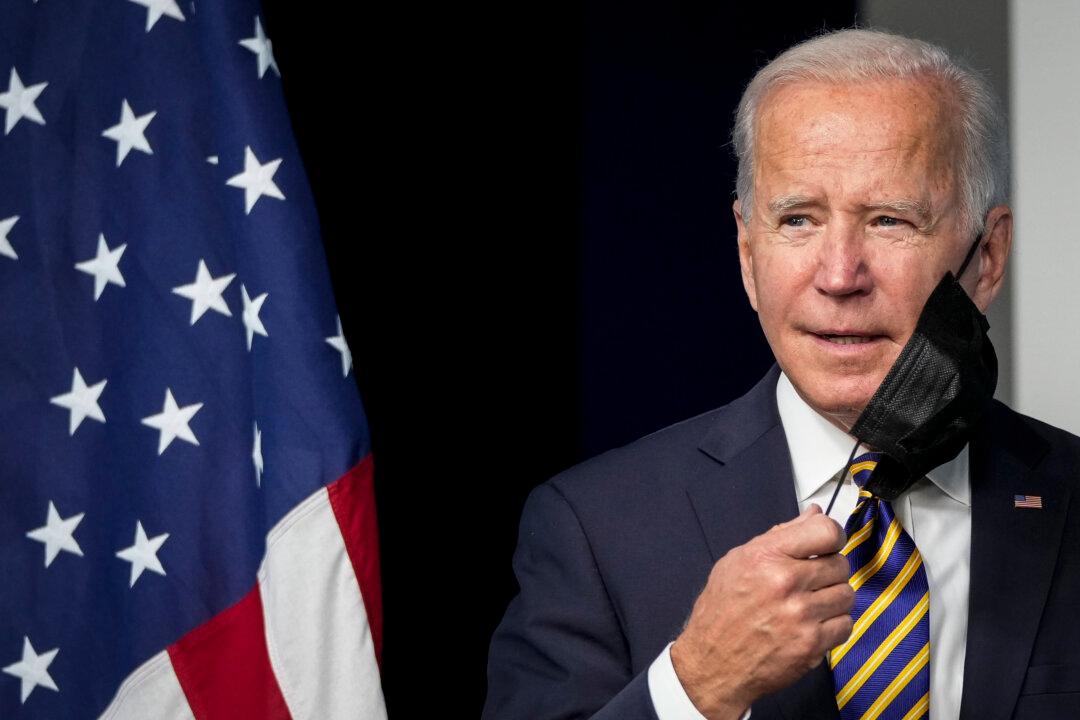

A new analysis of the economic impacts of President Joe Biden’s Build Back Better budget reconciliation framework shows that, in contrast to the administration’s claims of a “zero price tag on the debt,” the spending plans would increase the federal debt by 2.6 percent in ten years.

The White House on Oct. 28 released a framework for legislative priorities to be taken up by the Senate in the budget reconciliation process, which provides for $1.87 trillion in new spending over a decade. Provisions include a focus on clean energy and various social programs.