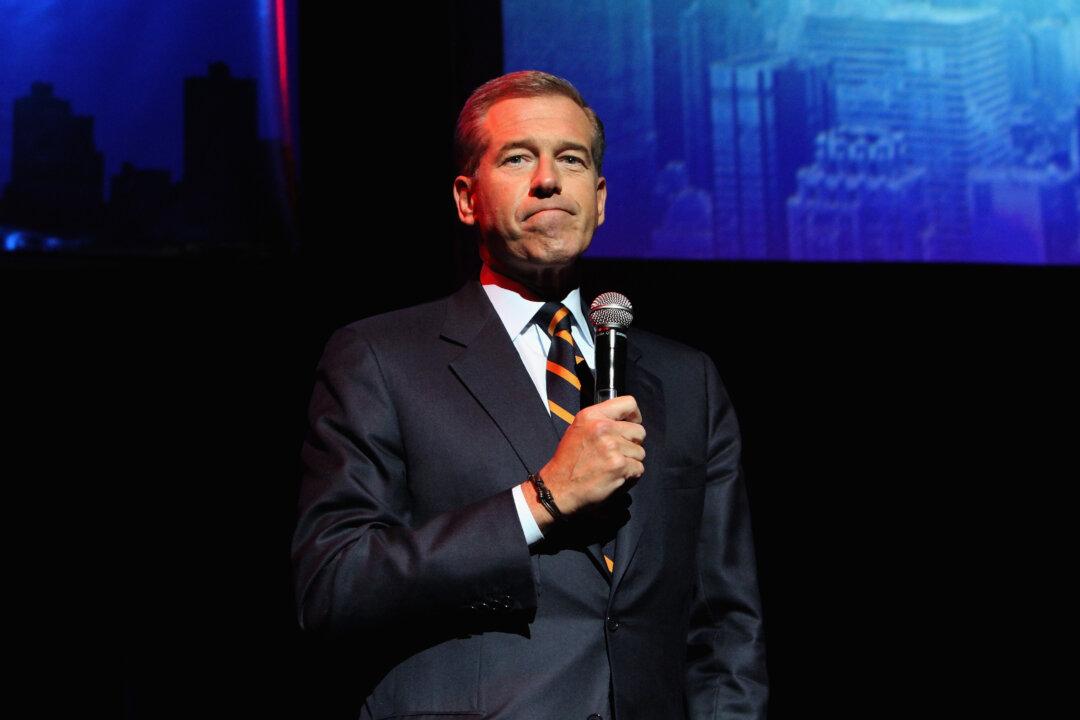

After being suspended without pay from NBC in February, Brian Williams returns to television this week. He won’t be heading back to the Nightly News desk (now anchored by Lester Holt), but he will be reporting breaking news updates on MSNBC, beginning with the pope’s visit to the United States.

Williams’ fall from grace at NBC came after he misrepresented, during a newscast, events that occurred while he was in Iraq in 2003. In a memo to staff announcing Williams’ suspension, president of NBC News Deborah Turness also expressed concerns about Williams’ misconstrued accounts of other events that had taken place while reporting in the field.

News reports indicate those concerns included Williams’ claim that he'd seen a body floating in the French Quarter in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, and even that Williams may have exaggerated rescuing puppies when he was a volunteer firefighter as a teenager.

The staff memo from Turness quoted Stephen B Burke, chief executive of NBC Universal, who said Williams’ actions were “inexcusable” and “jeopardized the trust millions of Americans place in NBC News.”

Of course, it would have been inexcusable if Williams had intentionally misled viewers about his reporting experiences to bolster his credibility.