Brian Williams was born too late.

Last month, the realization that the “NBC Nightly News” anchor had misrepresented experiences in Iraq led to a six-month suspension and outcry for his termination. His tales of harrowing experiences in the French Quarter during Hurricane Katrina in 2005 are also under scrutiny.

But Williams’s penchant for reaching and at times overreaching for eyewitness authenticity puts him in good company – with the reporters who stand at the very beginning of the Western tradition.

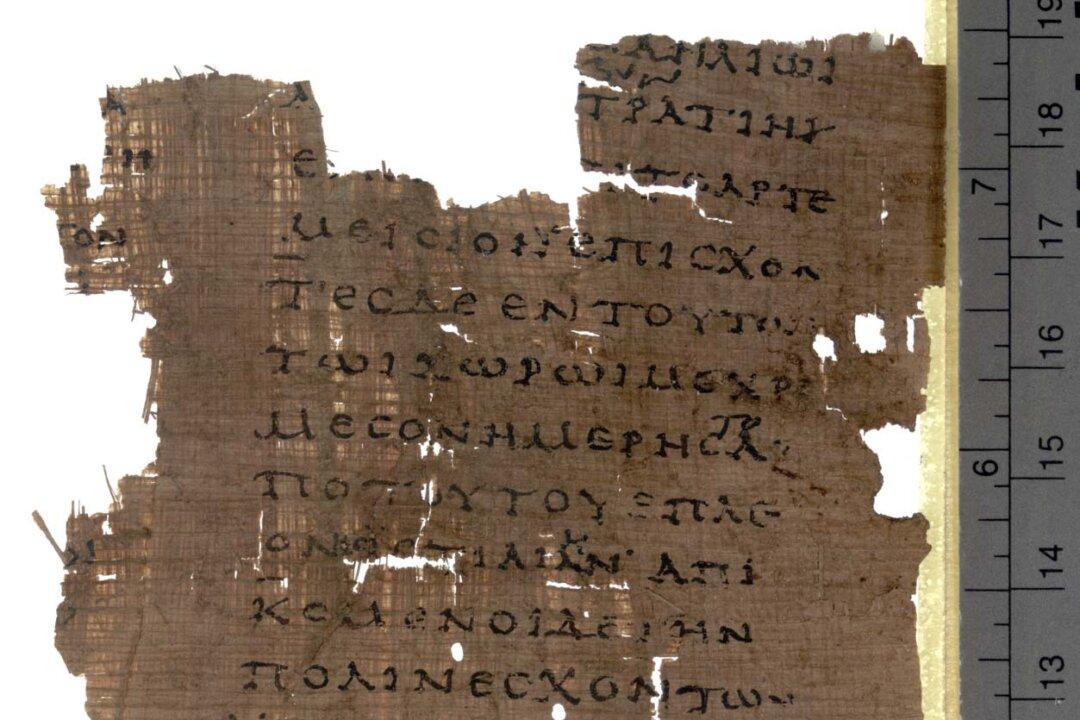

Eyewitness Reporting in Ancient Times

The historians of ancient Greece and Rome placed a high priority on eyewitness reporting, on being there and seeing for oneself.

Time and research “in the field” and the accompanying brushes with danger gave an historian credibility and authority. Eyewitness accounts also engaged the audience, who could follow in the footsteps of the author’s derring-do.

But in their efforts to win over their audiences, Greek and Roman historians also fudged or fabricated their time in the field.

Suspect Greek Measurements in Egypt

The Western historical tradition begins with the Greek Herodotus in the fifth century BCE. The second book of his Histories is a long and detailed discussion of the geography, history, and culture of the Egyptians, and it remains an indispensable resource for the study of ancient Egypt.