The ongoing turmoil in Egypt has put the kibosh on Canadian computer science teams’ plans to travel to the country to participate in the so-called Battle of the Brains, the finals for which were scheduled to take place in Cairo this month.

Teams from the University of Waterloo, Simon Fraser University, and the University of Alberta, which all placed in the finals, are waiting to hear where the contest will be re-located.

Brad Bart, a senior computing lecturer and the head coach for the SFU team, says his students are disappointed about the cancellation but remain optimistic.

“I think they were excited to get to go to somewhere as exotic as Egypt. But they still get to compete, so, we’re kind of waiting to see where the chips fall, where they’re going to hold the contest and when. Hopefully it will be somewhere as exciting,” he says.

The International Collegiate Programming Contest challenges the world’s top university computer science teams to use open standard technology in designing software that solves real-world problems. Each team of three students faces 8-12 programming conundrums with varying degrees of difficulty.

This year the SFU team overcame many challenges to win in the Association of Computation Machinery regional placement competition. The team was told after a judging error was found that although they had tried to solve the equations 25 times, that they had already won on the third try.

Brain Battle Delayed Due to Egypt Unrest

The Battle of the Brains finals scheduled for Cairo this month have been delayed due to the unrest in Egypt.

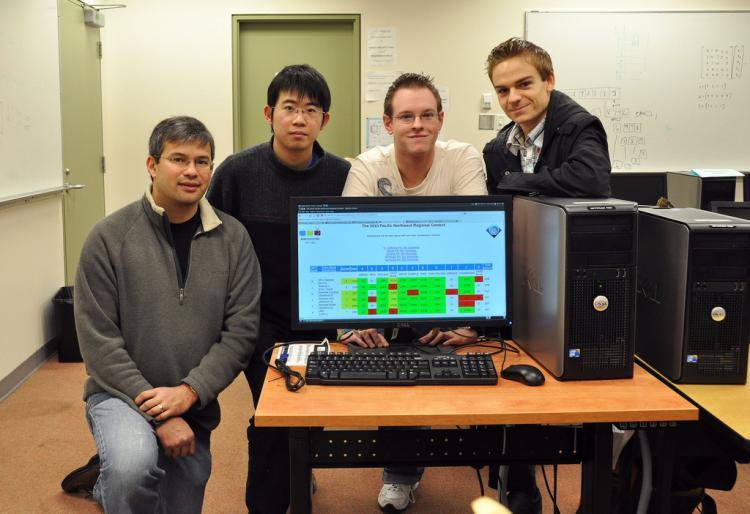

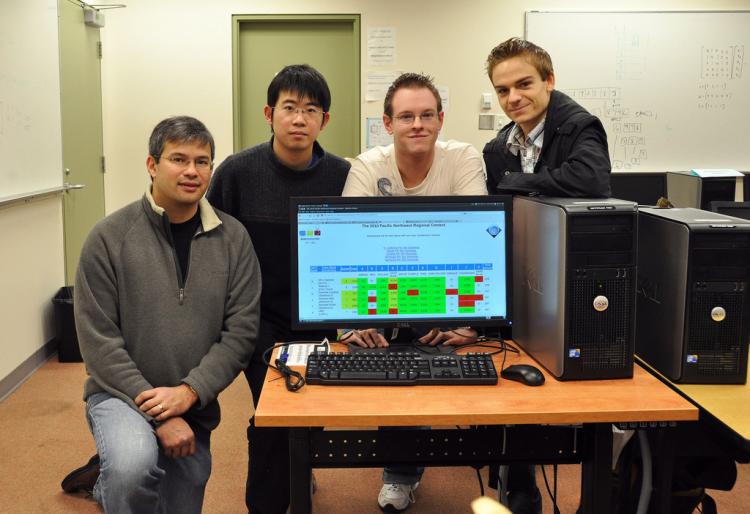

(L-R) Instructor Brad Bart and his Battle of the Brains team: Hua Huang, Wesley May, and Andrew Henrey. This month's finals in the International Collegiate Programming Contest will be relocated due to the unrest in Egypt. Simon Fraser University

|Updated: