NEW YORK—It was a day of haste and excitement as over a million students found their way to classrooms for their first day of school.

Among them were an unprecedented number of 4-year-olds. On Thursday Mayor Bill de Blasio kicked off his signature prekindergarten expansion with a victory lap to prekindergarten classrooms across the five boroughs.

He visited those hosted by public schools, community organizations, and religious schools, announcing the big enrollment number over 51,000.

Yet that’s not the final number. Not even by a long shot.

Far from the tapestry of public school classrooms and manifold community centers, there lies another world of pre-K, one that existed before the mayor’s entrance. It’s a world where you pay extra and trust that you will get what you pay for.

There are over 600 private schools in the city offering pre-K, according to GreatSchools’s web portal.

Horace Mann School

Just one block from Central Park on East 90th Street, Horace Mann (HM) School maintains an impeccable reputation after more than 120 years in business.

Marcia Levy, a slim lady of polished manners and the head of its nursery division, sits in an inconspicuous small office decorated with students’ artwork.

Interior of a prekindergarten classroom at the Horace Mann School Nursery Division on the Upper East Side, New York, Sept. 3. (Petr Svab/Epoch Times)

Stacks of paperwork suggest a busy administrator, yet she didn’t miss a chance to greet a parent with a wide smile, a long affectionate “Hi,” or a nonchalant “How are you?”

When explaining the school’s functioning though, she maintained the correctness of an experienced educator. “Teaching is an art,” she said.

The school follows the Reggio Emilia Approach, an education philosophy conceived after World War II by Italian pedagogue Loris Malaguzzi. It argues children should have some control over what they’re learning, even at an early age, focusing on “investigation, exploration, and discovery.”

Through observing, listening, and supporting, HM teachers detect the interests of their pupils and pinpoint a topic that will be included as a common thread throughout the school year.

For example, a relative with a limb in a cast inspired one pre-K class to model its own cast out of paper at the outset of the school year, which led to inquiry about recognizing bone fractures, understanding x-rays, and the looking into the inner functioning of the human body—a year-long project of the class.

With a plethora of physicians among the parents and relatives, children’s minds were enriched by the experiences of their kin who came in to talk about the profession.

Other classes picked building construction, marine life, or cars as their project, but whatever their choice, the same curriculum is woven in. Step-by-step, journal writing evolves into reading, and math games develop into arithmetic.

“It’s a wonderful philosophy,” said Levy, who taught preschool in Italy for five years.

Interior of a prekindergarten classroom at the Horace Mann School Nursery Division on the Upper East Side, New York, Sept. 3. (Petr Svab/Epoch Times)

The HM Nursery Division is not a large establishment. Its narrow corridors host 143 children in nine classes, 52 in pre-K.

The environment is as important as a “second teacher” in the Reggio Emilia philosophy, a lot of thought goes into every detail of the classrooms’ milieu.

Bright with daylight and filled with tiny furniture, the classrooms are a crossover between a country-house living room and a slightly magnified dollhouse.

Focus is on a wide range of objects children can touch and feel, but no flashy toys are in sight. Wooden and straw bowls are scattered about the furniture, filled with small pieces of wood lathed into different shapes, pebbles, and shells. “This is very Reggio,” Levy said.

(Petr Svab/Epoch Times)

The understated tone emphasizing natural materials is calming to children, she explained.

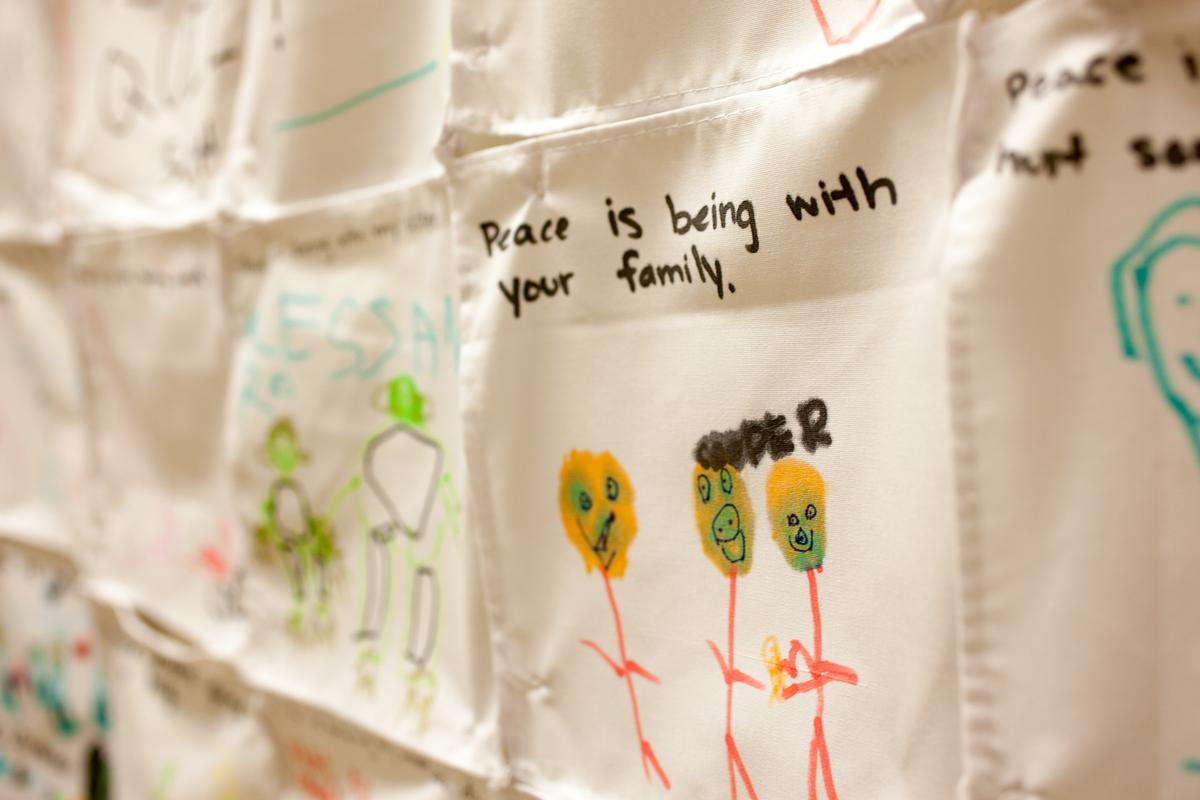

The Reggio philosophy replaces the term “assessment” with “documentation.” A child is not to be judged but listened to. Here children themselves take on a large part of the documenting.

Being routinely photographed, the children became interested in photography and their interest was to be respected. Slowly, over time, photography turned into an important part of the curriculum, Levy said.

Students learn how to operate a camera and extensively document their school lives. “It’s the world from the child’s perspective,” Levy said, referring to a series of framed photographs lining the first-floor hallway.

Students work lines the hallways of the Horace Mann School Nursery Division on the Upper East Side, New York, Sept. 3, 2014. (Petr Svab/Epoch Times)

Most stunning though is the students’ portraiture work. “They capture each other in a way that’s quite extraordinary,” Levy said. Lines of captivating expressions fill their yearbooks.

Levy starts her fifth year with the school. When she first came, the experience was magical, she said. “We have wonderful resources, possibilities to dream for children I never had before.”

Raising World Citizens

Compared to the more established schools, Avenues: The World School, is hardly born yet. Entering its third year, this “research-based” institution occupies a 10-story reconstructed warehouse building in Chelsea, bordering the High Line park.

It developed its own philosophy to prepare students “for life in a world with continuously fading borders.” It fits in everything, from college preparation, to time management and exercise regimens.

Nancy Schulman, head of Avenues Early Learning Center, is a hearty and approachable former long-time director of the renowned 92nd Street Y Nursery School. She walked me through slick white corridors lined with 33-inch screens and mounted iPads while explaining the school’s pre-K.

Interior of a prekindergarten classroom at the Avenues: The World School, in Chelsea, Manhattan, Sept. 3, 2014. (Petr Svab/Epoch Times)

In order to raise citizens of the world, children pick either Spanish or Mandarin Chinese and spend half their school days in a class where teachers only speak the foreign language. Such an approach, called immersion, helps them to pick up the language fast, but as most come to the school knowing only English, teachers have to dance and gesticulate, show pictures—whatever it takes to make themselves understandable. Fortunately, children are better at getting the meaning than adults, Schulman said.

Periods of play time, partly at a rooftop playground, alternate with learning literacy in both languages, movement classes, music classes, sciences classes. “Most of the learning is done through hands-on activities,” Schulman said. “It’s not the teacher giving the information, but creating experiences for the children.”

Rooftop playground with a stylization of the American flag at the Avenues: The World School in Chelsea, Manhattan, New York, Sept. 3, 2014. (Petr Svab/Epoch Times)

Classrooms feel a bit like IKEA showrooms, only filled with books and toys. The focus on languages is everywhere, from Chinese and Spanish story books to trilingual signage. “You don’t see a school that looks like this,” Schulman said.

Avenues plans to eventually open campuses across the world. Right now it’s working on one in China.

Screens in a hallway of the Avenues: The World School, in Chelsea, Manhattan, Sept. 3, 2014. (Petr Svab/Epoch Times)

Despite their differences, both the Horace Mann and Avenues pre-Ks have a number of features in common. Both their directors have over four decades of experience. Both use the same writing instruction. Both offer supports but not special classes for students with disabilities. Both have at least two teachers for classes of 16–17 students. Both said they are aware of the Common Core, a set of learning standards central to the nation’s current education reforms, but both expressed confidence their approach goes beyond it.

Incidentally, both also have roughly the same tuition.

Just one question remains then: Is it all worth the $43,000 a year?