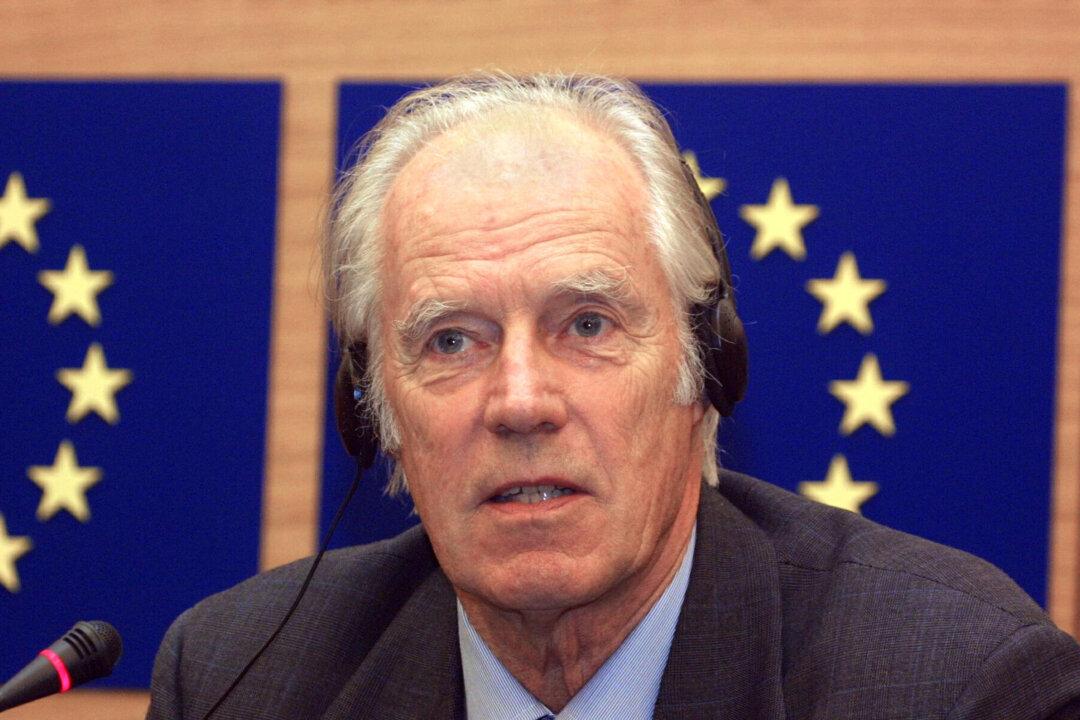

LONDON—George Martin, the Beatles’ urbane producer who quietly guided the band’s swift, historic transformation from rowdy club act to musical and cultural revolutionaries, has died, his management said Wednesday. He was 90.

“We can confirm that Sir George Martin passed away peacefully at home yesterday evening,” Adam Sharp, a founder of CA Management, said in an email.

Sharp called Martin “one of music’s most creative talents and a gentleman to the end.”

“In a career that spanned seven decades he was an inspiration to many and is recognized globally as one of music’s most creative talents,” Sharp said.

Beatles drummer Ringo Starr tweeted: “God bless George Martin peace and love to Judy and his family love Ringo and Barbara. George will be missed.”