TOKYO—Japan’s central bank surprised the financial world and pleased investors Friday by intensifying its purchases of government bonds and other assets to try to revive a chronically anemic economy.

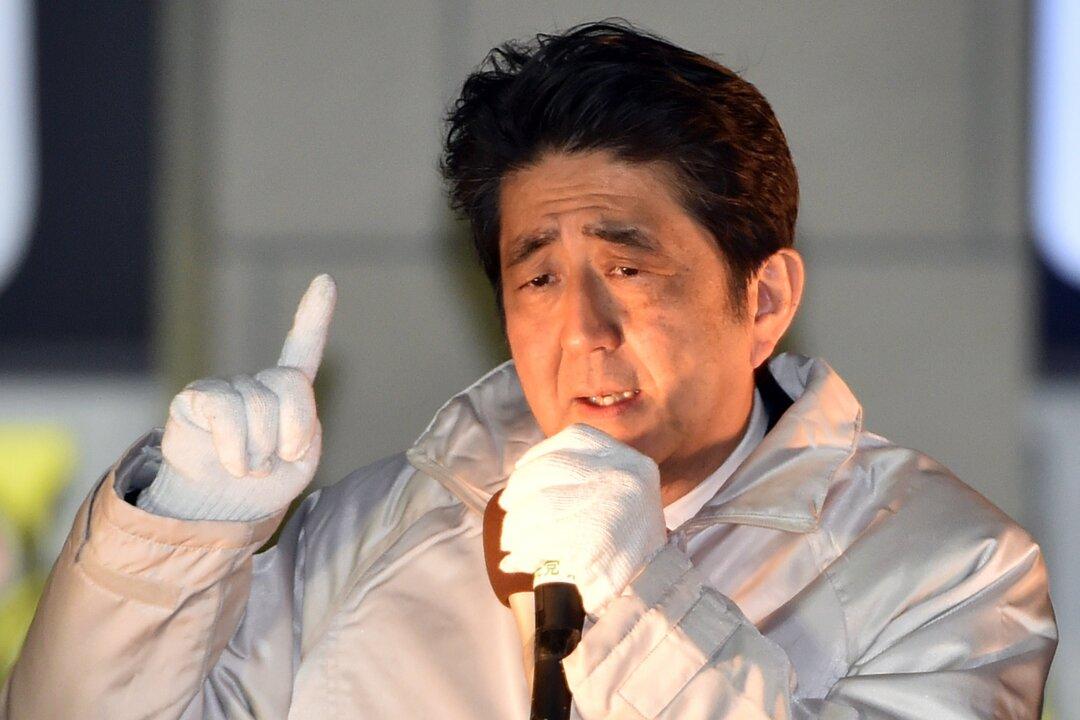

The Bank of Japan’s move to pump trillions more yen into the financial system is intended to stimulate spending in the world’s third-largest economy. It’s an acknowledgement that Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s government has so far failed in its broad efforts to revive growth, especially after a sales tax hike took effect in April. The latest data show consumer spending falling, unemployment rising and excessively low inflation dipping further.

By injecting more money into the economy, the government hopes to raise expectations of higher inflation and thereby encourage people to spend and fuel growth.

Coinciding with the central bank’s move, Japan’s $1.1 trillion public pension fund acted Friday to move money out of low-yielding bonds and into higher-yielding but riskier stocks to try to improve its investment returns and meet its obligations to a swelling number of retirees. Abe said the move was needed to ensure that the fund can meet its future obligations. Japan is rapidly aging, and its population is shrinking as birth rates decline.

Across the world, investors responded by pouring money into stocks in anticipation that the Bank of Japan’s action would mean lower bond yields, higher stock prices and a cheaper yen, which would make Japan’s goods more affordable overseas.

After the government’s announcements, Japan’s Nikkei 225 stock index soared 4.8 percent to close at a seven-year high, and the dollar rose 2 percent against the yen. European stock markets also jumped, along with the Dow Jones industrial average.

The central bank said it will increase its purchases of government bonds and other assets by between 10 trillion yen and 20 trillion yen ($91 billion to $181 billion) to about 80 trillion yen ($725 billion) annually.

The move is striking in its timing: It comes two days after the U.S. Federal Reserve did the reverse by ending its own asset-purchase program, which had pumped $3 trillion-plus into the U.S. economy over the past six years. The Fed is pulling back because, in contrast to Japan’s, the U.S. economy is showing consistent improvement.

The Bank of Japan’s move raises pressure on the European Central Bank to follow suit. The ECB has been considering aggressive steps to invigorate the ailing eurozone economy, which is suffering from weak growth and too-low inflation.

Ultra-low inflation can hurt an economy because it typically leads people to postpone purchases in expectation that prices will go even lower. It also makes the inflation-adjusted cost of loans more expensive. And it raises the risk of deflation — a drop in prices, wages and the value of stocks, homes or other assets that can further slow spending and tip an economy into recession.

Japan has been stuck in a deflationary trap for most of two decades — a big reason its economy has barely grown.

It’s far from clear that Japan’s latest move will succeed where Abe’s government has so far failed in a multi-pronged effort to boost growth and inflation.

BOJ Gov. Haruhiko Kuroda said the action was need to prevent a reversal into a “deflationary mindset” that has stymied growth by discouraging spending.

Countering such a trend is “the most important thing we can do,” Kuroda said. “Whatever we can do, we will.”

Harumi Taguchi, an economist at IHS Global Insight, said the Bank of Japan was spooked by signs the economy could slip back into deflation. The Bank of Japan had declined at its last meeting Oct. 7. But the “pressure had increased over the past few days and weeks,” Taguchi said. “There was a mounting sense of urgency.”

A measure of core inflation, which excludes volatile food and energy prices, has fallen to nearly 1 percent, Taguchi noted. Falling oil prices could push overall inflation even lower. And a planned increase in the nation’s sales tax next year could weaken spending and growth.

Such a tax would raise the sales tax by an additional 2 percentage points to 10 percent, after the sales tax rose from 5 percent to 8 percent in April. This year’s tax hike was intended to reduce Japan’s enormous debt but has slowed the nation’s fitful economic recovery. Abe is expected to introduce supplementary spending to try to cushion the impact of the tax.

The central bank said its stimulus spending would continue as long as needed to attain an inflation target of 2 percent. In addition to stepping up asset purchases, the Bank of Japan will triple its purchases of exchange-traded funds and real estate investment trusts and increase the average maturity of the assets it holds to 10 years from seven years.

Its main decisions on expanding its stimulus passed by a 5-4 vote, revealing a sharp split among the bank’s policy board members.

Analysts noted that by reducing the yen’s value compared with other currencies like the U.S. dollar, the Bank of Japan’s moves would likely give Japan’s exporters a competitive edge.

“We will all benefit ultimately from a successful Japan,” said Lewis Alexander, chief U.S. economist at the investment bank Nomura. “Maybe it’s a slight drag to the U.S. economy in the short term. But if this contributes to the long-run success of Japan, we'll all be better off.”

Q&A: Why Japan’s Economy Needs More Juice

Japan is pumping more money into its lagging economy, expanding an already lavish stimulus effort. The surprise announcement Friday highlights diverging fortunes among the world’s top economies. Earlier this week, the U.S. Federal Reserve ended its own unprecedented stimulus in a sign of increased confidence in economic recovery.

Who’s Splashing the Cash?

The Bank of Japan is increasing its annual purchases of government bonds and other assets by as much 20 trillion yen ($91 billion) to 80 billion yen ($725 billion). It hopes to spur more lending, spending, investment and inflation by increasing the amount of money in circulation. The Fed’s bond buying program totaled $4 trillion, much bigger than the BOJ’s program but it is still significant relative to the size of Japan’s economy.

Why Is Japan Doing the Opposite of the Fed?

Japan’s recovery shuddered to a halt after the government increased sales tax from 5 percent to 8 percent in April. It had to because the Japanese government has the developed world’s heaviest debt burden. But the hit to growth was worse than expected and officials worry the economy won’t bounce back. A 1997 tax increase stalled a recovery from the collapse of Japan’s 1980s bubble economy. BOJ Gov. Haruhiko Kuroda says “whatever we can do, we will,” to counter a deflationary spiral.

Will It Work?

The BOJ’s decision was not unanimous. Four of 9 members of its policy-making panel voted against the extra stimulus. Markets, however, rejoiced. The Nikkei stock index surged 5 percent. A sustained rise in stock prices could make some Japanese feel richer but any wealth effect faces strong headwinds from an aging and shrinking population. The yen dived against the dollar, which could help Japan’s exporters; however the benefits of a weak yen have been diminished in recent years by companies moving production overseas.

From The Associated Press. AP Business Writer Matthew Craft in New York contributed to this report.