Jung Chang, like so many other Chinese born in the 1950s, grew up a member of the cult of Mao Zedong.

“I grew up seeing Mao as a god,” she said of the former Chinese ruler. “If what we said was true we would say ‘I swear by Chairman Mao’.”

Even when her father and grandmother died in the Cultural Revolution, she still refused to blame Mao for the tragedies.

It was only when Chang, the renowned author of the highly successful Wild Swans, read an article in a contraband copy of Newsweek, about Mao, that she came to understand just how directly responsible her leader was, for the deaths of massive numbers of Chinese people. This and other factors helped lead her, along with co-author Jon Halliday, to write Mao: The Unknown Story, a new biography of the Communist leader.

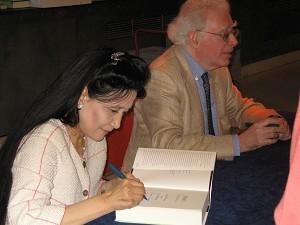

Chang, appearing alongside Halliday at a book promotion event in New York, said that most Chinese people still don’t know the truth about Mao.”

“The people don’t have the information they need to make an intelligent judgment on Mao,” she said. “The Communist government wouldn’t give people the information they need. Mao is written into the Constitution. It is illegal to be against Mao.”

Chang emphasized her point by pointing out that both Wild Swans, which describes the horrors of the Cultural Revolution, and her Mao biography are strictly banned in China.

She mentioned that although some things had changed, strict censorship had not.

“I think Mao wouldn’t recognize today’s China,” she said. “The economic achievements in China have been done after Mao died and because he died.”

“But Mao would recognize some things, such as the control of information… Chinese people aren’t able to see anything critical of Mao and only things in praise of Mao.”

This biography, which contains new information gleaned from interviews with Mao’s friends and relatives, information from archives, and other sources, helps to debunk some of the popular myths about Mao. For example: Mao was a defender of the peasants (Mao had no sympathy for the peasants and had little regard for human life in general); Mao was fiercely patriotic (Mao actually consented to the idea of the Japanese occupation of China); and Mao was a dyed-in-the-wool Communist (Mao originally considered working for the Nationalists and only fully joined the Communists after the Nationalists forced him out).

Asked if she had written the Mao biography out of hatred, Chang said, “Hatred is not the word I would like to use … I think a deep outrage is how I feel. I mean it’s no secret that my family suffered in the Cultural Revolution, that my father died, that my grandmother died.”

She pointed out that some of the book’s most shocking exposes, such as the fact that Mao was exporting food to Stalin for arms at the same time that tens of millions of Chinese were dying during the late 1950s, were even hard for her to believe, but the appalling facts were backed up by painstaking research.

Chang said that Mao’s direct knowledge of the tragedies he caused, shocked her as she was working on his biography.

“In Wild Swans I wrote that tens of millions of deaths convinced Mao that his policies were wrong, and he changed them,” she said. “But then again as we realized … from documents, actually, Mao didn’t want to stop and said for all his projects to take off, ‘half of China may have to die’.”