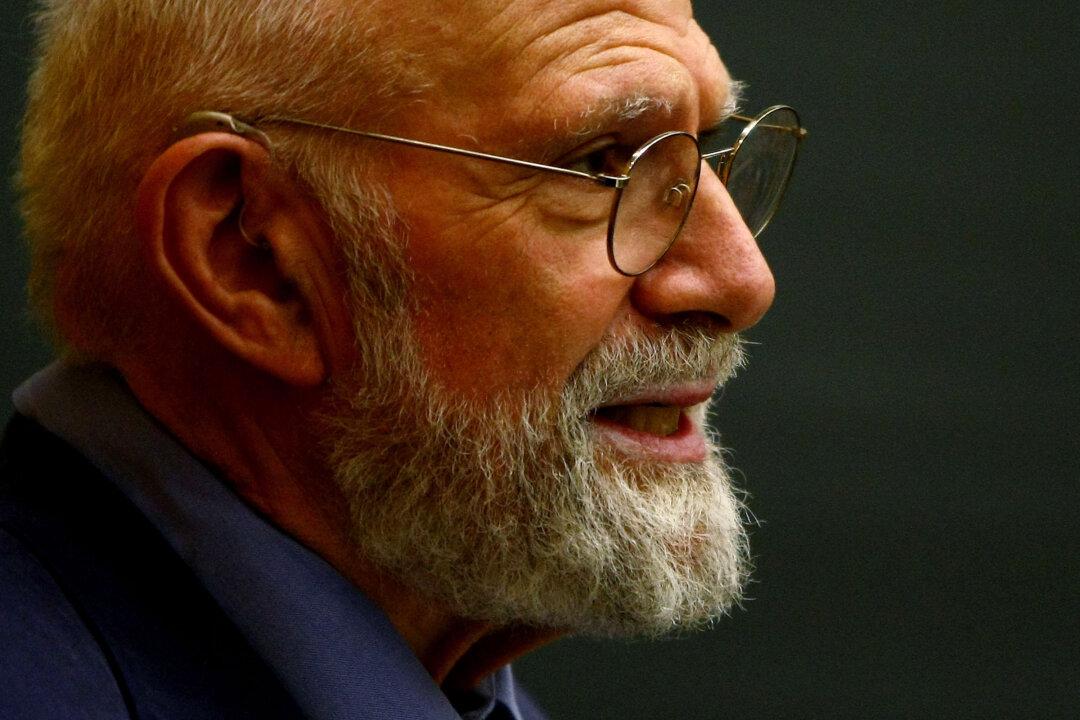

Neurologist Oliver Sacks has made startling and fantastic discoveries about how the human brain works by daring to challenge conventional notions. He has brought clinical case studies to the public in vivid narration, merging literary sensibility and medical precision—highlighting a human connection to the minds he’s studied.

“Over the last few days, I have been able to see my life as from a great altitude, as a sort of landscape, and with a deepening sense of the connection of all its parts,” he wrote in an essay for the New York Times published Feb. 19. At the age of 81, Sacks has learned he has multiple metastases in the liver, a fatal condition. He wrote the essay to reflect on his life and pending death, reflections we may experience in more depth when his autobiography is published this spring.

“I cannot pretend I am without fear. But my predominant feeling is one of gratitude,” he wrote. “I have loved and been loved; I have been given much and I have given something in return; I have read and traveled and thought and written. I have had an intercourse with the world, the special intercourse of writers and readers.” Though he feels some detachment from life, he is not finished living. He intends to deepen his friendships, write, travel, and spend final moments with those he loves. But he will not read about politics or the problems of the world. Though he remains concerned about them, “these are no longer my business; they belong to the future,” he said.

“I rejoice when I meet gifted young people,” he said. “I feel the future is in good hands.”