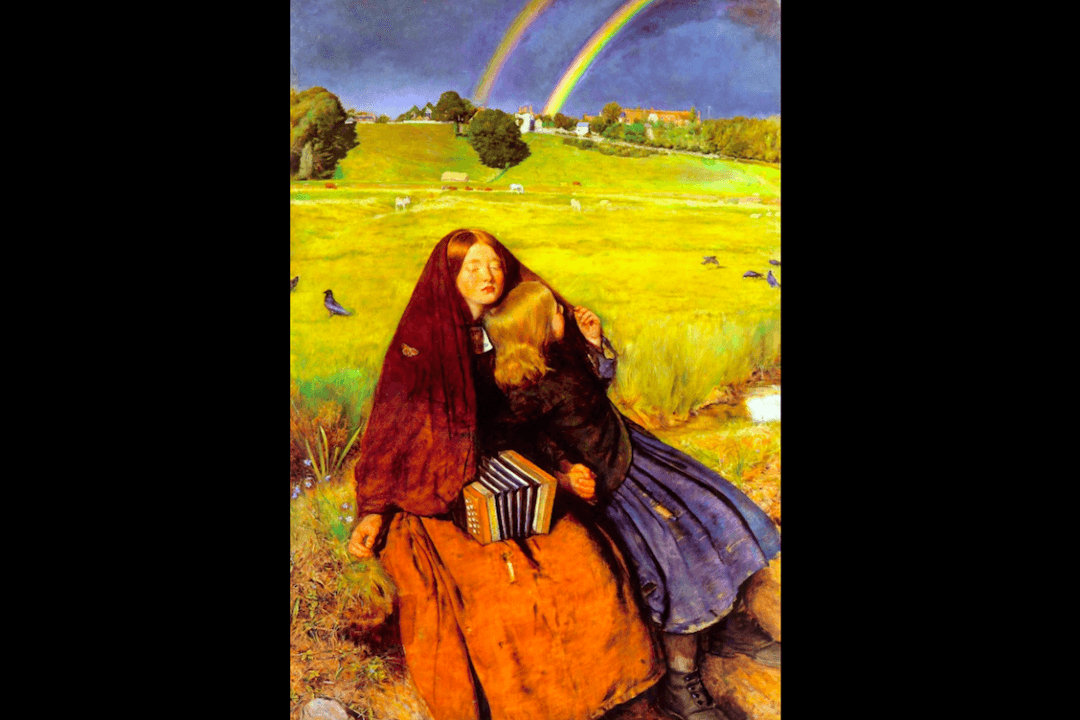

Every life on this planet is interconnected to and dependent upon one another. “The Blind Girl” by John Everett Millais illustrates, with a firm grasp, our interdependency.

Millais, one of the founding pre-Raphaelites, in an attempt to steer away from what he thought of as opulence and decadence in British art of the time, based his works on the ethos “truth to nature.” The idea was to take inspiration from nature, rather than gloss over the human figure and existence in a stylized fashion.

In “The Blind Girl,” we see two girls in raw and realistic form. Millais is trying to show us something.

Empathy

Millais uses the landscape and subtleties of the girl’s posture to convey that she is blind. The creek behind her could possibly be heard trickling and flowing past the reeds and rocks. The butterfly landing on the girl’s shoulders suggests she is still.

The town of Winchelsea can be seen in the distance, beyond the pastures. Above it, the sun shines. The blind girl seems to be soaking in its radiant warmth.

Millais connects us to the scene with the senses. We wonder about the lives in the painting even more as the flush of detail piques our curiosity.

What was Millais trying to portray in “The Blind Girl?” He never wrote it down. The remarkably detailed painting, down to the individually painted blades of grass makes the scene believable to the viewer. We are there with the girls, sharing their plight.

Together

The painting, for me, is a subtle reminder that no matter what we do, we are not alone, we interact with others in some capacity or another in nearly every aspect of our lives. In the painting, we are shown the dependence of one girl to another.

The two girls, without a doubt, need each other to survive. The little blonde girl’s gaze towards the town in the distance makes the viewer imagine their journey ahead. Their postures and clasped hands suggest that they have been on many roads together already.

Millais paints such a scene of togetherness in his time. It is a welcome reminder that brings to mind a quote by Aristotle on his view of companionship, “Friends hold a mirror up to each other; through that mirror they can see each other in ways that would not otherwise be accessible to them, and it is this mirroring that helps them improve themselves as persons.”

Timothy Gebhart is an artist residing in Kaukauna, Wis. His website is www.tgebhart.blogspot.com